Over the past two months, Ronald Pies and Allen Frances, in response to a post I had written, wrote several blogs that were meant to serve as an “evidence-based” defense of the long-term use of antipsychotics. As I read their pieces, I initially focused on that core argument they were presenting, but second time through, the aha moment arrived for me.

Their blogs, when carefully parsed, make a compelling case that their profession, in their use of antipsychotics as a treatment for multiple psychotic disorders, has done great harm, and continues to do so today. Indeed, they make an argument for prescribing protocols that would mimic the selective use of antipsychotics by practitioners of Open Dialogue in Tornio, Finland.

Now, Pies and Frances would not see their blogs in this light. But it is easy to show that their posts, in their description of who benefits from antipsychotics and who does not, lead to that conclusion. In their defense of antipsychotics, Pies and Frances have—unwittingly, for sure—sounded the bell for radical change.

My January Blog

This “dialogue” began several months ago when, in response to a challenge from Frances, I set forth my “opinion” on what the scientific literature has to say about the long-term effects of antipsychotics. I think there is a history of science, stretching back 50 years, that tells of drugs that worsen long-term outcomes for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (in the aggregate.) At the end of that post, I set forth what I believe—again, based on the scientific literature—would be a “best use” protocol for prescribing antipsychotics:

- Try to avoid immediate use of neuroleptics in first episode psychotic patients, as there will be a significant percentage who will recover without the medications (but aided by other forms of treatment), and this is a good outcome for those patients.

- Once the medications are used, there should be an effort to minimize their long-term use, with regular support for drug-tapering protocols.

.

From a conventional medical perspective, there is nothing radical about prescribing a class of drugs in that “selective use” manner, and that is so regardless of whether one thinks that the drugs worsen long-term outcomes. With any prescribed drug, it is important to figure out for whom the drugs provide a benefit, and for how long the drug should be prescribed. All drugs are understood to have risks, and thus, if you prescribe the drugs to patients that don’t receive a benefit, you are doing harm to those patients (and that is particularly true if the drug is an antipsychotic, which has so many known adverse effects.) Perhaps that means never prescribing the drug in the first place to certain patient groups, or prescribing the drug for a limited period of time. Not all patients with a given diagnosis are necessarily the same, and thus it is good medicine to try to develop prescribing protocols that incorporate “for whom” and “for how long” distinctions among patient groups.

The “radical” part of my blog is my belief that the scientific literature reveals that antipsychotics, on the whole, worsen long-term outcomes. That was the aspect that France and Pies were intent on countering, but in the course of doing so, they identified types of psychotic patients who could recover without antipsychotics. In doing so, they revealed that their profession’s prescribing habits, by failing to account for that fact, do great harm.

Their Response

Frances wrote three blogs in response to mine; one on February 1, a second on Feb. 16, and a third on Feb. 22. He begins his first blog with a declaration of his beliefs:

- Antipsychotics medications are used far too often in people who don’t need them.

- Even when necessary, doses are often too high and polypharmacy too common.

- Antipsychotics are neither all good, nor all bad. Used selectively, they are necessary and helpful. They are harmful when used carelessly and excessively.

.

Frances then sets forth this principle for distinguishing patients who don’t need long-term antipsychotics. “It is a truism throughout medicine,” he writes, that “good prognosis patients don’t need long term meds; poor prognosis [patients] do.” Next, he identifies some of the types of psychotic patients that fall into this “good-prognosis” category:

“Psychotic presentations vary greatly in cause, severity, chronicity, prognosis, and appropriate treatment. Many psychotic episodes are transient. Some are stress related—e.g., a soldier in combat, a college kid or traveller who becomes delusional when away from home. Some are a transient part of mood disorder and remain quiescent if the mood disorder is successfully treated. Some are related to substance intoxication or withdrawal. Some are caused by head trauma or medical illness. And some normal people have hallucinatory experiences that cause no impairment and have no clinical significance. Transient psychotic symptoms in the above situations may require a short course of antipsychotics. Generally this can be done without much risk of return of psychosis—assuming the stressor, substance problem, mood disorder or medical problem has resolved. Bob and I would agree on short term or no antipsychotic treatment for such transient psychoses.”

Antipsychotics, Frances concludes, should be used over the long-term to treat “psychotic symptoms that are severe and impairing.” He writes:

“Antipsychotics have many grave disadvantages that make them a last resort. They suppress symptoms, rather than curing them. They can cause unpleasant side effects and dangerous medical complications. They contribute to shortened life expectancy. And they are subject to wide overuse even when there is no indication. We should be extremely cautious and selective in their use quite independent of Bob’s tenuous claim that they worsen psychosis.”

Putting aside the “tenuous claim” part of that sentence, I couldn’t agree more with the main point Frances is making. Prescribers should be “extremely cautious and selective in their use.”

Having set out this “best use” model in his first blog, Frances devotes his second blog to arguing that antipsychotics do not worsen psychotic symptoms over the long-term, and thus makes the case that “going off antipsychotic medication is usually a bad bet for the severe and chronically ill.” This is the patient group—those who are severely and chronically ill– that benefits from the drugs, he writes, and even “among those who previously had chronic psychotic symptoms, perhaps 20-30 percent will have improved enough over time that medication is no longer necessary.” He sums up his argument in this way:

“There is no ‘one size fits all’ in psychiatric treatment. Meds are not all good or all bad. Misapplied they are bad. Prescribed properly they are good. It is incorrect to generalize from any one person’s lived experience to everyone else’s lived experience. Meds that are harmful for someone who didn’t need them may be essential for someone who does.”

All of this—as the basis for a prescribing protocol–sounds quite reasonable. One-size doesn’t fit all, and thus the obligation for psychiatry as a medical specialty—if it agrees with Frances’ survey of the patient landscape—is clear. Psychiatry would need to adopt a three-step protocol:

- Psychiatrists would need to inform first-episode patients that they might have a transient psychosis, and thus they would initially treat them without antipsychotics, and instead take a “watch and wait” approach to see if symptoms began to abate on their own. This delayed initial use of neuroleptics would be important because once a person is on an antipsychotic, his or her brain goes through a series of compensatory adaptations, and that can make it difficult to go off the drug.

- If, after a watch-and-wait period, an antipsychotic was prescribed and the patient got better, psychiatrists would then try to taper them from the medication, since it was understood that “good prognosis” patients don’t need “long-term meds.”

- Psychiatrists would reserve continual antipsychotic use for those patients who, after some period had elapsed, had developed severe and chronic symptoms.

.

Pies’ does not make as clear a case as Frances for selective use of antipsychotics. But start with his title: “Long-term antipsychotic treatment: effective and often necessary, with caveats.” Often necessary also means “often not necessary,” and thus, once again, there is a need to develop a selective-use model that distinguishes between the two groups. Indeed, as Pies’ mounts his defense of antipsychotics, he repeatedly emphasizes that he is writing about their effectiveness as a treatment for schizophrenia, and of the need to distinguish this group from other psychotic patients.

“It is important to understand that only a portion of people with a first psychotic episode have schizophrenia, which is usually a very chronic illness. Many have quite brief bouts of psychosis that never return, making long-term antipsychotic treatment unnecessary.”

Thus, Frances and Pies make a case for selective-use protocols that would consist of prescribing the drugs over the long-term to chronic patients, or, in Pies’ case, to patients with “schizophrenia.” But then Pies and Frances fail to follow their argument to its obvious conclusion: Prescribing antipsychotics long-term to other types of psychotic patients who don’t need them is doing great harm to them. These drugs, as everyone acknowledges, have many adverse effects.

And here is the reason for the harm done: American psychiatry long ago adopted a one-size-fits-all approach to prescribing antipsychotics for psychotic disorders. Patients diagnosed with a psychotic disorder are regularly told they need to stay on these drugs for life. Furthermore, psychiatry’s “evidence base” for antipsychotics naturally leads to that prescribing practice.

The “Evidence-Based” Path to Prescribing Failure

The basis for the best use of a medicine begins with diagnosis. A diagnostic manual is supposed to provide both reliability and validity, and thus enable physicians to distinguish between different discrete diseases. Even if presenting symptoms of two diseases are similar, the underlying pathology may differ, and thus the prescription may be different for each disease.

Pies writes as though schizophrenia is a discrete illness, which can be readily diagnosed as different from other psychotic disorders. Psychiatry does often speak of schizophrenia in this way, and treat it as such in its research, but most in the field, when pressed at all, will acknowledge that this diagnosis is a catchall term. Instead, they will say there are a “group of schizophrenias,” which may have many different biological causes. Thus, even within the “schizophrenia” category, there may be many different types, with differing long-term outcomes.

In addition, there are many other diagnoses for psychotic patients (other than schizophrenia). The universe of psychotic patients includes both the “group of schizophrenias,” and those with psychotic disorders of milder types. The one element that is supposedly common to all these patient groups is psychosis, but psychosis is a catchall terms for a lot of different symptoms—paranoid thoughts, hearing voices, disordered thinking, and so forth. So you have disparate symptoms piled atop disparate diagnoses, and yet as psychiatry tests the efficacy of antipsychotics, both as a treatment for an acute episode of psychosis, and for reducing the risk of relapse once a patient in on the drug, it lumps all these disparate types into one group, and declares its drugs effective for treating psychotic episodes and preventing relapse.

That is deficiency number one in psychiatry’s evidence base for antipsychotics. The field developed a one-size-fits-all method of using the drugs, based on studies that lump many different patients into one category. That research, which lumps different patient types together, can’t possibly provide an evidence base for the selective-use model that Frances and Pies are advocating.

The second deficiency in psychiatry’s evidence base is rather stunning, as it flies in the face of conventional wisdom. Although antipsychotics have been used for more than fifty years, and there have been innumerable short-term trials, there still is a lack of evidence that these drugs are effective for the short-term treatment of a first or second episode of psychosis.

In a 2011 Cochrane review of this question, John Bola found that nearly all short-term trials of antipsychotics have been in patients previously exposed to antipsychotics (or in patients first withdrawn from antipsychotics and then randomized either to placebo or to drug.) He searched the scientific literature for randomized trials of antipsychotics in patients experiencing a first or second episode of schizophrenia (or psychosis), and could only find five studies that met his inclusion criteria, with a total of 998 patients. There was no clear result that emerged from those studies, leading Bola to conclude that “data are too limited to assess the effects of initial antipsychotic medication treatment on outcomes for individuals with an early episode of schizophrenia.”

In other words, it may be that antipsychotics do not reduce psychotic symptoms better than placebo over the short term in newly diagnosed patients. This opens up the possibility of delaying initial use of the drugs, to see who can recover without them, and we can find evidence for the merits of that approach in a 1961 report by the California Department of Mental Hygiene. When the department studied discharge rates for all 1,413 first-episode schizophrenia patients hospitalized in California mental hospitals in 1956, a it found that 88 percent of those who weren’t prescribed a neuroleptic were discharged within eighteen months, whereas only 74% of those treated with a neuroleptic were discharged within that time period. This is the only large-scale study from the 1950s that compared discharge rates for first-episode patients treated with and without drugs, and the investigators concluded that “drug-treated patients tend to have longer periods of hospitalization. . . . The untreated patients consistently show a somewhat lower retention rate.”[1]

However, psychiatry’s evidence base for short-term use does not incorporate such findings. Instead, it looks to evidence collected from randomized trials in more chronic patients, with prior (or current) exposure to an antipsychotic. These studies do show the drugs to be superior to placebo for reducing symptoms over the short term. But then they are interpreted as showing that antipsychotics are an effective treatment for all psychotic episodes, and thus they are seen as providing evidence for treating all psychotic patients, including first-episode patients, with antipsychotics.

This is deficiency number two in psychiatry’s evidence base. The field has adopted a “one size fits all approach” for the acute treatment of psychotic episodes, without making a distinction between first episodes of psychosis and eruptions of psychosis in chronic patients.

Psychiatry’s evidence base for long-term use of antipsychotics comes from relapse studies, both in schizophrenia patients and in patients with other psychotic disorders. The relapse rate is regularly higher in the drug-withdrawn group, and this is seen as evidence that antipsychotics reduce the risk of relapse, and hence the need for continual use of antipsychotics. But even putting aside the many design flaws in those studies, the studies still don’t provide evidence that all patients should remain on antipsychotics forever. There are many in the placebo groups of those studies that don’t relapse, and thus the relapse studies actually provide a rationale for figuring out which patients could do okay off the drugs long-term.

Yet, once again, the relapse studies are cited as a one-size-fits-all finding, and psychiatry then adopts a protocol that leads, in real-world practice, to the recommendation (and insistence) that all patients with a psychotic disorder remain indefinitely on antipsychotics.

In sum, psychiatry has created an evidence base for prescribing antipsychotics that militates against the selective use of the drugs. It is an evidence base that leads to treating all psychotic patients with a “one-size-fits-all approach,” even though, as both Frances and Pies acknowledge, many psychotic patients have a transient disorder, or may have a “good prognosis” at outset, and thus do not need lifelong treatment with an antipsychotic. The harm that comes from this flawed one-size-fits-all evidence base is obvious: It leads to the lifelong drugging of many patients who, in the absence of such medication, could recover or at least do fairly well.

Quantifying the Harm Done

To quantify the harm done by psychiatry’s one-size-fits-all prescribing practice, it would be necessary to identify the percentage of all first-episode psychotic patients that would fall into the group described by Frances and Pies as not needing antipsychotics. Psychiatry really has never sought to answer that question, not in any robust way, and so the challenge is to pick through the existing research literature to identify long-term recovery rates for first-episode patients who weren’t initially treated with antipsychotics.

The first such data comes from research studies conducted between 1945 and 1955 (the decade before the arrival of antipsychotics.) As I wrote in Anatomy of an Epidemic, those studies found that 65% to 80% of all first-episode schizophrenia patients would be discharged within 12 to 18 months, and that at the end of five years, perhaps two-thirds of the initial cohort would be living in the community. This was before the federal government had established disability programs for the mentally ill, and so those discharged patients were, at the very least, living in the community without the aide of government subsidies. In a later retrospective study, Bockoven also found that roughly two-thirds of psychotics patients treated with psychosocial care in 1947 were living independently in the community five years later.

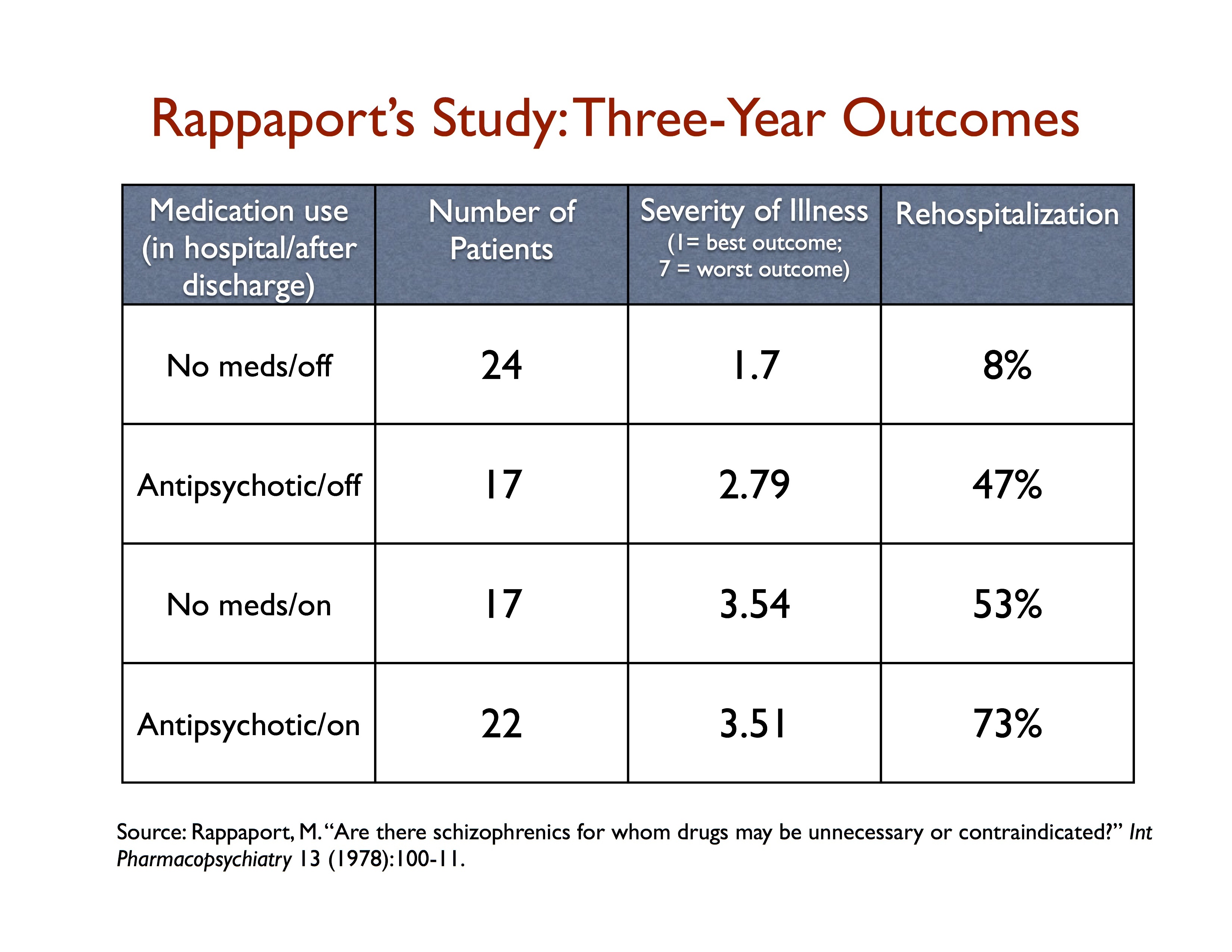

We see something like this—two-thirds doing fairly well over longer periods—in a handful of studies conducted in the 1970s by the NIMH that were designed to revisit the merits of antipsychotics. In Maurice Rappaport’s study, 24 of 41 first-episode schizophrenia patients randomized to the non-drug arm recovered and never needed to go on antipsychotics during the three-year study, and this never-exposed group had by far the best outcomes among all the patients.That suggests that a watch-and-wait period could serve as an escape valve for perhaps 60% of all first-episode psychotic patients.

At Soteria House, 40% of the first-episode schizophrenia patients never needed to go on antipsychotics at the end of two years, and another 40% needed them for only a time. Only 20% used the drugs continuously.

The results from Open Dialogue Therapy in Tornio, Finland also suggest that, with the proper initial care, 80% of first-episode patients can do well without antipsychotics, with most of this group never needing to go on the drugs in the first place. Indeed, perhaps this is the actual brilliance of Open Dialogue therapy. It incorporates a drug-use protocol that allows patients to sort themselves out by type. It first identifies one group of psychotic patients that never need to go on the drugs (65%); a second group that may find such treatment helpful over the short term, but doesn’t need the drugs long-term (15%), and finally a third group—20% of the initial cohort of first-episode patients—that may benefit from the drugs over the long-term. At outset, the Open Dialogue team doesn’t know which of the first-episode patients will fall into these three different medication-use categories; it has developed a method for keeping people safe until patients reveal their varying medications needs.

In his blog, Frances stated that he supported the “Open Dialogue” approach in Finland, but without discussing its selective-use drug protocol. But Open Dialogue does not just point to a better way, it also points out the harm done by psychiatry’s one-size-fits-all drug protocols. Eighty percent of first-episode patients may have the potential to do well without the drugs, but American psychiatry’s “evidence-based” protocols expose that group to long-term antipsychotic use, and thus to long-term harm.

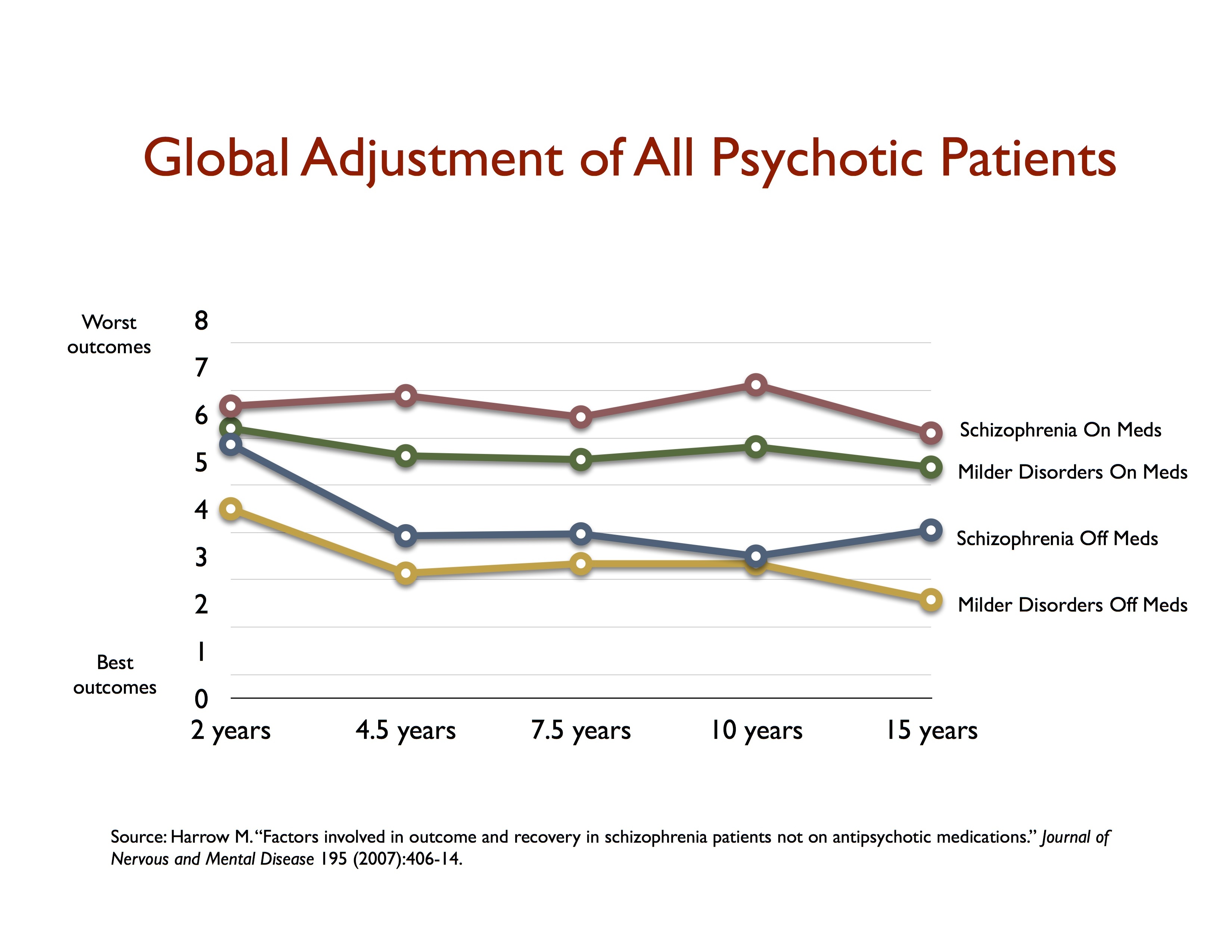

We can see the extent of this harm quite clearly in Martin Harrow’s long-term study of psychotic patients. At the end of 15 years, there were 81 people in the study who, at baseline, had milder psychotic disorders. The majority of people in this milder category stopped taking antipsychotic drugs early on, and as a group were doing quite well—their collective scores fell into the recovered category. But those with milder psychotic disorders at baseline who continued taking antipsychotics were more impaired in their functioning at 15 years than those diagnosed with schizophrenia who subsequently stopped taking antipsychotics. (See graphic.) This is a result that tells of how psychiatry “evidence base” for antipsychotics can transform a person with a milder initial illness into a chronic, seriously impaired mental patient over the long term.

It is easy to imagine what Frances and Pies might say in response to this blog. They would likely argue that most psychiatrists are able to distinguish between those who need the drugs and those who do not, and regularly taper many of their psychotic patients from antipsychotics. Indeed, here is what Frances wrote in his third blog: “Most psychiatrists do a good job of diagnosis, prescribing meds, and providing support . . . Results overall for psychiatric treatment are good. The majority of patients improve at rates equal to, or above, those achieved by doctors treating medical illness.”

But, as was seen above, psychiatry’s evidence base for antipsychotics, which states that the drugs are effective over the short term for curbing psychosis and effective for reducing the risk of relapse, does not promote such selective-use prescribing, and, indeed, any survey of 100 people diagnosed with a psychotic disorder in the past 25 years would find that most had been told they needed to take the drugs for life. Frances and Pies, in their blogs, were seeking to defend psychiatry’s prescribing practices and the long-term effectiveness of antipsychotics, but the caveat they expressed—that the drugs are effective for a certain subset of psychotic patients—naturally focuses attention on the drugs’ effects on those who don’t need them long-term, and that leads to a finding of great harm done.

And that finding, in turn, supports a demand, based on Frances and Pies own writings, for a radical rethinking of psychiatry’s use of antipsychotics.

In a follow-up blog, I will respond to their review of the “evidence” for the long-term effects of antipsychotics. That provides another an opportunity to watch their minds at work as they sift through the evidence. What studies do they dismiss? What studies do they embrace? This is a review that ultimately leads to this question: Do we see, in their assessment of the scientific literature, evidence of the critical thinking that we want to see present in a medical specialty that has such a large impact on our lives? And if not, what shall we do?

[1]L. Epstein, “An approach to the effect of ataraxic drugs on hospital release rates,” American Journal of Psychiatry 119 (1962): 246–61.

Frances and Pies LIES….and tell the truth too, at the same time!

God Bless you, Robert Whitaker!

Happy St. Patrick’s Day!

I’ll tell my psych drugs horror stories here tomorrow!

After all, I’m living proof of the lies of the pseudoscience drugs racket of psychiatry….

PIES LIES, and Frances AIN’T NO SAINT!….

Report comment

Good post Robert. I find it interesting reading your analyses as they come from the mind of someone who is a journalist with a very analytical, investigative, logical mind… and I presume not someone who suffered from severe “mental illness” or treated those suffering from it… but someone whose distance from having or treating the problem gives them, to my mind, a certain objectivity that it might otherwise be difficult to have.

Let me comment as I read through, from my perspective as someone who took antipsychotic drugs for years and was in extreme “psychotic-like” nonfunctional states as a young person…

I would read these statements from Frances, “psychotic presentations vary greatly in cause, severity, chronicity, prognosis, and appropriate treatment”… as an admission that problems labeled schizophrenic are primarily non-medical and that his profession’s position on severe psychosis being a brain disease is a fabrication.

It is ironic to hear this man, Allen Frances, who I call Janus (after the Roman two-faced god) because he first presided over the massive increase in medicalization/diagnosis, then once he had profited to the tune of millions, turned into a critic… it is ironic to hear this man admit that “antipsychotics… (are) a last resort”, and even admit that they shorten life expectancy, and yet he is so focused on defending them.

The problem with the notion of “the severely and chronically ill” and “the good and bad prognosis patients” is that there is no reliable way of identifying who passes the boundary and qualifies as severely ill… and given certain interventions, some who are severely ill may move out of that area of the continuum and become moderately / mildly “ill”, to use the inappropriately medical language for emotional suffering. Thus “prescribing drugs properly” is going to be very difficult given the lack of precision or validity of psychiatric diagnosis. In fact, it is impossible.

Prognosis is an inappropriate word for human emotional problems. Our struggles are too complex, individual, and modifiable to be split into “good and bad prognosis.” In this regard, Frances is thinking in a simplistic, split way reminiscent of borderline thinking…. this is the fantasy that psychiatry is an objective medical discipline. It is not, and it never will be.

Meanwhile, Frances’ ideas do not consider very much what the client and their family want. The idea, as usual, is of doing what the psychiatrists consider best, as if their view should be valued more than the family and the experiencer.

One should ask, about Pies’ title: “Effective and often necessary”…. Effective at what? The answer is effective at dulling down the person’s ability to feel so that they are progressively less able to deal with their emotional conflicts or to function.

As for “schizophrenia”, Pies’ writing is already dead and buried at this point. The ignorance and stupidity of this assumption are incredible… There is no schizophrenia distinguishable from other psychoses: Here is Van Os’ manifesto again making this point – https://www.schizofreniebestaatniet.nl/english/

Every young psychiatrist should be required to read Mary Boyle, Richard Bentall, Jeffrey Poland, Stuart Kirk, Jim Van Os, to understand that the notion of a discrete entity called schizophrenia is an illusion. It’s not there. A real continuum of psychosis does exist, and people at the severe end of it tend to get labeled schizophrenic. But there is no reliable way of determining when someone is or is not in that part of the continuum, and that part of the continuum is not a discrete disease. This paradigm of psychiatry is so last-century… is it too profitable to give up?

Furthermore, Pies writes that many people labeled schizophrenia have a very chronic course… that is false, and is a borderline blatant lie on his part. He really should know better. The WHO studies and the Vermont study refuted this myth long ago… 70% of the people meeting criteria for so-called schizophrenia in Open Dialogue got completely well… 75% of those in the Gifric program in Quebec, who were all schizophrenic, got well… how does Pies not know this? Is he really an expert? I feel sorry for the people labeled schizophrenic that have to see Pies as their psychiatrist….

Robert, you should have made the case that schizophrenia is not valid… Pies is very weak in his support for this fallen idol, schizophrenia. Challenging this diagnosis in America must eventually be done.

Ok, now I read further… train of thought going while I read the article… and see that you did this! Wow… great. The “group of schizophrenias” is an acknowledgement of the continuum/spectrum-like nature of psychotic experience. This was known by psychiatrists like Bleuler/Kraepelin long before Pies… people who were wiser than him, apparently.

It will be interesting to see if Frances or Pies acknowledges or addresses the diagnostic problem. They probably will not. It is their Achilles heel… Denial and avoidance must be used by them to protect the holy grail that does not exist… schizophrenia.

You are right that a treatment based on unscientific diagnoses cannot be evidenced based… yep…

Even if drugs do reduce psychotic symptoms more than placebo in the short term for newly diagnosed people… it does not mean that they are “better” than not having drugs. Psychotic experiences can be meaningful and voices/hallucinations can be useful cues about past relational trauma and what a person is terrified of. Terror is the core of psychosis… and if a person cannot face their fears with a supportive other, they will probably not get better. Thus even if drugs do damp down the “symptoms”… it doesn’t mean they’re “better” for the people they are given to. That is the judgment of the psychiatrists. It’s not our judgment.

Again, relapse is not necessarily a bad thing to be terrified or avoided… a return of psychotic experience can indicate that very difficult emotions are being triggered, and this can be an opportunity to work things through in a different way. One must examine the assumptions behind what psychiatrists say and do… so often they are just bullshit.

In this picture here – https://bpdtransformation.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/cam00157update2.png – “Autistic-presymbiotic schizophrenia” – is the “poor prognosis” group that they are talking about… the most severely disturbed people who have often been through the most horrendous abuse and neglect. These are the people considered by psychoanalysts of old to have “nuclear or process schizophrenia” and today considered as the most severely mentally ill. But their prognosis can actually become good given sufficient support over a long enough time. Rinsley and Searles wrote about this type of long-term work… rarely available today. You can see in the diagram that “schizophrenia” is not distinguishable from “borderline” which is in turn not distinguishable from “narcissistic/neurotic” etc… problems fade into one-another; there are no discrete illnesses in early emotional development.

To add to the “no drugs, good outcomes list”… would be the data from Gottdiener’s meta-analysis available on psychrights, the 388/Gifric program’s results from French-speaking Quebec, the outcomes for people in Mauritius who were labeled schizophrenic before drugs reached the island… written about by Matt Irwin and available on psychrights, the results achieved by many ISPS therapists and written about in books by authors like Vamik Volkan, Bryce Boyer, Ira Steinman, Murray Jackson, and others…

What Frances should admit is that American “schizophrenics” have a quality of life that – mostly sitting at home, watching TV, not working, or even on the streets and in prison – that is much worse than people in poor countries who are less often given drugs. The WHO results by Hopper supported this idea, and the recent international study by Haro confirmed that advanced-nation psychotic people are still doing worse, although now that more drugs are in poor countries they are doing worse too. Results overall for psychiatric treatment are not good. It sucks balls. People hate it…

“What shall we do?” Great, provocative question.

Thanks for encouraging dialogue with this article Robert…

Report comment

Great analysis of Allen Frances! Agreed on almost everything you said. Although, not the parts that sort of had traces of the DSM. Although I agree, with all the points made.

Mostly wanted to say that, but a side note, I believe Bob has a plan as far as the most effective points to critisize. Of course, he has a website that allows for different people to approach in different ways. I think that’s part of the plan as well. It would make sense, because it’s such a complex, and difficult situation. The problems, are deep and vast. The solution would take all of us contributing in the best way we can. Think this is important!

Report comment

I think neither Allen Frances nor Ronald Pies are being completely sincere, that is, what they give, in terms of concessions, are a matter of fighting critics with their own words. Allen Frances can point to “the pathologizing of normal” and then separate that group from the “seriously sick”, and Ronald Pies can accuse critics of criticizing a non-issue with the “chemical imbalance theory” while extending a wink to colleagues overdosing patients. You’ve essentially got two defenders of, if not the orthodoxy, then the original mission, that is, promoting the medical profession as the answer to what are seen as afflictions of the mind. Wouldn’t it be nice if they’d take a serious look at those long-term studies that have been conducted? Right now, I think that’s a pipe-dream, however, there is certainly no reason we can’t use their words, in the same fashion in which they would try to use ours, against them. Somebody, after all, might be paying attention.

Report comment

Here is an interesting chart to look at showing how abysmal the US sickcare system is:

http://www-tc.pbs.org/prod-media/newshour/photos/2012/10/02/US_spends_much_more_on_health_than_what_might_be_expected_1_slideshow.jpg

The US is spending an astounding 150% more than other advanced nations on average for its healthcare, and yet its people live less long than the average person in other advanced OECD nations.

Antipsychotic drugs can be tied into this overall picture. They are just another area where corporations and their doctor-lackeys lie about the need for large-scale “treatment” (in this case, based on fabricated “disorders”), and then outrageously overprice the drug while bilking insurers/their clients, in order to gouge the middle and lower class people who are deluded into believing they need said treatment.

It is strange to be a rare undrugged person living among so many ignorant, docile, drug-taking sheep.

Report comment

This has been a big issue for the last several years to no avail. US healthcare has proven not worth the money.

What isn’t talked about is the fact that psychiatry (the scam that it is) and health care are beholden to pharmaceutical companies. Together this trio generates so much revenue that the economy would tailspin out of control should any of the three “pillars” fall. So then it becomes an issue of the government to be beholden to the three and to be complacent and compliant (the FDA, congress, senate, etc) to prevent the collapse. However, this approach like so many others our system perpetuates and condones, are not sustainable. Eventually, the house of cards will fall. If for no other reason because there are not enough taxpayers who can afford to continue to support it, to pay for healthcare or to purchase legal drugs. At this point your most correct analysis of “ignorant, docile, drug-taking sheep” will speed the process up because they currently do not see with open eyes but also will not be able to work in the future. Your child drugged by psychiatry today does not seem to be your STEM employee of tomorrow if he/she is employable at all.

Psychiatry is a failure and those who defend it will eventually fall with it.

Report comment

Sorry but its not about long term outcomes, its about keeping undesirables – people with undesirable behavior doped up and quite.

It is entertaining to watch the psychiatric establishment try so hard to pretend otherwise.

Report comment

I don’t disagree, that’s one reason. A big reason, and probably also the root cause in the beginning. While, now it also makes quite a profit. Only, right now, they are claiming to be concerned with long term outcomes. So, as long as they are claiming this, and people are taking their word for it, it’s a basis we have to argue. Although, it rough, and my cynicism only get’s higher. Hopefully, something, somewhere will click for the better soon. At least I hope to see a chance of this.

Report comment

As far as I know they measure whats a good and bad long term outcome with things like the number of arrests and hospitalizations.

They have an advantage because if a people are lobotomized with Zyprexa and sit in front of the television in an anhedonic state all day long instead of doing life they absolutely will have fewer arrests and hospitalizations as a group.

They gave me that Zyprexa for anxiety and insomnia, I think I was accused of “schizoaffective disorder” long story but I can tell you that anhedonic state resulting from a Zyprexa lobotomy is a fate similar I would Imagine to death because its like impossible to enjoy anything. I even went to the natural history museum and felt no awe and wonder. That anhedonic state is like living death maybe that’s how the slang became “zombie”.

So anyway the debate of long term outcomes to me is over because I know what a “better” outcome on the drugs feels like and they don’t put that in the long term outcome judgement equations.

And that stuff keeps you sick cause it GAVE me a wicked psychosis during withdrawal I never had BEFORE when I quit the stuff to get my feelings back.

Report comment

“The_cat” speaks the TRUTH. details differ, but our story lines are the same…. I once spent 6 months in a State Prison, *pre-trial* – no conviction – on 1,000mg.s/day Thorazine, plus a few other types of pills….Prison is bad enough, but the akathisia, and other EFFECTS of the drugs made it a living hell. It still haunts me 30 years later. I didn’t know it was gonna turn into a sentence of LIFE WITHOUT possibility of parole…. “Schizo-affective” simple means, “it LOOKS LIKE schizophrenia, but isn’t, so we’ll call it “affective”, to sell more drugs, and keep the SCAM going”…. Now, I’m 20+years shrink-free…

GOD BLESS YOU, Mr. Whitaker. Your work WILL SAVE LIVES….

> meow < 😉

Report comment

Well, you and I are in agreement, but my point was how can we get others to see? Like I said I’m growing cynical. However, the small chance I do see, makes this conversation seem unavoidable. However, perhaps something else will click first, and we can bypass this. However, for now getting people to see this, although daunting seems necessary, even if it seems never ending.

Report comment

I think I know how you feel, Kayla…. For years I’ve said, “Psychiatry and its’ poison pills has done, and continues to do, far more harm than good.” I know that. You know that. We know that. But the “we” here on MIA isn’t the *WE* who needs to hear it. The pharmaceutical industry, and Gov’t, and Wall St., and even Global Traders, all all together in a big ball of $DRUG$ RACKET$. It makes money for rich and powerful people. We here think Pharma & the AMA, and APA actually *care**about*people, but they don’t. They only care about money and power. The more drugs they sell, the more money they make, and the more money they make, the more power they have, so they sell more drugs, to get more money, to have more power to sell more drugs, to have more power to sell more drugs, to get more money, to have more power, to sell more drugs, to get more power to sell more drugs to make more money to get more power to sell more drugs to get more money to sell more drugs to get more power, and are you getting the picture? The EVIL ONES won’t listen. Maybe we need a 2nd Amendment solution to the lies of the pseudoscience of psychiatry. Maybe Mr. Whitaker should get a Nobel Prize, or at least a Pulitzer. How do we nominate Whitaker for a PULITZER????….

(I’m thinking I need to take a few days off, and not think about this stuff, to clear my head a bit! ….. Thank-you, Kayla, for all you do! I, for one, like your comments! Have you written a letter to your local newspaper?….

Report comment

It’s also about keeping innocent child abuse victims, esspecially those abused by religious authorities, “doped up and quiet.” Particularly since, according to the medical evidence, 2/3’s of so called “schizophrenics” today are child abuse or ACEs survivors.

http://psychcentral.com/news/2006/06/13/child-abuse-can-cause-schizophrenia/18.html

Not to mention, keeping those who’ve dealt with prior easily recognized iatrogenesis and / or adverse drug reactions “doped up and quiet,” too. You know, to proactively prevent potential malpractice suits for the incompetent and / or ignorant or misinformed doctors.

These are psychiatry’s primary functions, according to an ethical pastor of mine, who claimed this unethical behavior to be, “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions.”

Report comment

Yeah, but it doesn’t even work for that purpose. A certain percentage of the “doped up” are far more dangerous than they were before starting their “treatment.” But of course, it’s always easy to blame “the disease” for their outbursts of violence, rather than looking at the fact that the best “treatment” available appeared to be unable to prevent and may have caused the violent behavior psychiatry is charged with deleting out of existence.

Report comment

A clever doctor might even take advantage of such a situation Steve. A ‘weapon’ which has no fingerprints on it? I was surprised to learn how easily this could be achieved when the environment is controlled.

Report comment

In fact, an excellent resource when one desires a negative outcome but, and I quote, “don’t have the stomach for it”.

Report comment

I was a chronic case myself in the early 1980s until I did stop taking “antipsychotics” and I was diagnosed as even more chronic as a result of the difficulty I had in stopping.

The one thing that Open Dialogue substantiates is that the psychotherapy does work for “Schizophrenia” (so it should be the approach used).

If Open Dialogue can deliver an 80% Full Recovery rate then the remaining 20% might gain from other “psychotherapies”.

My own recovery came through the support of self help groups ( – these groups are specifically suitable for certain types of people).

Report comment

Fantastic! You really seem to be tying things together, very well. Quite impressive you’ve managed to pull this together, from looks like to me to be deliberate attempts to dilute, and confuse. Almost don’t know what to say.

Report comment

Excellent blog, Robert, and absolutely since the psychiatric industry has chosen a “one size fits all” approach. Which results in drugging everyone initially, and leaving all, including the 60-80% who do not respond well to their drugs, on the drugs for life. Supposedly to prevent what’s known as drug withdrawal induced super sensitivity manic psychosis. The psychiatric industry is absolutely doing more harm, than good. I look forward to your follow up blog.

Report comment

Can we please all keep in mind that these drugs are being used in countless numbers of CHILDREN, almost entirely for purposes of behavioral control. And what I mean by that, is that even if you believe in the whole “childhood bipolar/brain illness” fraud, much of child psychiatry’s use of these brain damaging drugs is ADMITTEDLY TO CONTROL BEHAVIOR. In their own words, “to reduce irritability in children with autism (or honestly any disorder)”, to break and prevent temper tantrums or “meltdowns”, and I kid you not, EVEN AS SLEEP AIDS!

Report comment

Exactly. And the fact is that the so-called “antipsychotics” should never be given to children with autism, at all for any reason. Of course, they really shouldn’t be given to anyone really but they are really detrimental to kids that deal with autism.

Report comment

Procedure:

A rage outburst was defined as sufficient agitation and loss of control such that the child was unable to “time out” (i.e. sit in a chair for 10 minutes on being told to do so) or was a danger to himself or others and a higher level of intervention was needed. In order to compare the efficacy of medication against usual treatment (i.e. seclusion/restraint), a first rage outburst in the hospital was treated non-medically; that is, the child was placed in an isolation room. The door remained open if the child was able to regain control and take the time out in the room; otherwise the door was closed. If there was a second episode, the child was told “You need some medicine to help you get back in control. Take this medicine or we may have to give you a shot”. If agreeable, the child was given 0.015 mg/kg of liquid risperidone.

Read the study done by threatening children with painful injection here http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2990969/

A “rage outburst” was defined as (i.e. sit in a chair for 10 minutes on being told to do so…)

They should be put on trail for crimes against humanity.

Report comment

I was hospitalized several times in the years between about 91-92 to 97 before beidermans risperdal and “bipolar boom” had really eve taken off, before things were even nearly as bad as they’ve been in this millennium. My longest hospital stay was 4 and a half months in a state mental hospital at the age of 13. All of these hospitalizations were a result of coercion by the state amid custody battle over the fact that the schools insisted I be drugged (and later that I had to go to school, even after my parents arranged for me to be professionally home schooled) but soon after I began complaining about the drugs, my parents realized they were screwing me up and started to fight back.

The state hospital was by and far the worst when it came to drugging (Hawthorn center in Northville / Livonia, still open and going) as EVERY child was put on haldol as a matter of course. I was on it within the first 20 minutes that I got there, at the time having had no outbursts or seen any sort of medical professional at all. While billing the tax payers what had to be at least several hundred dollars a day, the 4 and a half months I spent there were just a matter of putting me in a routine and keeping me drugged. Waking me up every morning, sending me to “class” (a sort of school simulation where you didn’t have to actually do any school work, just sit there while some guy pretended to be a teacher), three meals a day, an hour of quiet time (everyone in their rooms) some recreation time and then bedtime.

They did nothing to try to help me with anything at all. They collected all that tax money just to keep me drugged while keeping me away from my family. At the time I did have serious social, psychological and emotional problems from the hell psychiatry and the schools had put me through up to that point, but they couldn’t have cared less about that. Not to mention all the drug-induced problems I had up to and beyond that point.

Report comment

The amount of medication used in children, especially those with Autism to control behaviour never ceases to amaze me and it is now the norm. Even heard of peadiatricans given parents a script for Ritalin when the diagnosis is handed over, even when the parent has not had any concerns with behaviour, just his lack of talking and not interacting with others. The parent was told the kid would need to be on it for life. Then the other day I got this:

Our 6yr old son was prescribed Lovan (Prozac) 20mg today by his pediatrician. His already on 2.5mg of risperdal, 72mg Concerta and 10-20mg of Ritalin in morning. .5 of Risperdal and 10mil of melatonin at night.

Risperidone is used so often as a self aid it is beyond me. Handed out as though it is candy. Well actually it seems to be seen as safer than candy, and all because no one can be bothered teaching a child HOW to go to sleep. Children need to learn how to settle themselves to sleep, as they are going to wake up during the night and cannot get themselves back to sleep if they do not know how to. They need to be put to bed AWAKE, but these days, we have kids falling asleep on the couch in front of the telly and being lifted to bed, then they wake up in the middle of the night, as everyone does but do not know how to get back to sleep, because their body only knows how to sleep in front of the TV. Equally you have parents who pat the child to sleep, and again, not a problem, providing you intend to sit by the bed all night and pat them back to sleep when they wake up, but it doesn’t happen. Most parents these days know nothing about basic child development and have never babysat, or even touched a baby prior to the one they give birth to, and most do not have extended family around to give them advice or even if they are they dismiss it as not relevant and out of touch with current parenting. Peadiatricans are not giving parents advice about how to teach the child to go to sleep, and even GP’s are handing out Resperidone when parents go complaining about their 18 month old not being able to sleep, saying it will teach the child to sleep.

The medication does not have the desired effect, they become agitated as a result and all sorts of other problems develop, which are all side effects of the med’s, but never seen that way and then the poor kid just ends up on one med, after another med, after another med and it gets to the point that no one knows what the presenting problem was in the first place. Even when they are offered good therapeutic support, in terms of autism, best practice is speech therapy, occupational therapy and psychology, all three working together, the child is so doped up they have no hope of gaining from any of it, and the parents are so tried from the child still being so agitated and out of control that they are not able to listen to anything anyone says.

I would estimate that by the age of 10, over 80% of those with a diagnosis of ASD are on some sort of psychotropic medication.

The fact that 99% of parents of children with autism do not understand the difference between temper tantrums and meltdowns does not help either. They either see everything as a temper tantrum and want to control it all and punish the child, or they excuse everything as a meltdown and then wonder why the child’s behaviour gets more and more out of control. Equally so much of therapy done with children with autism is to make them look normal, so even just standing still and flapping arms, without touching or annoying anyone will result in some cases with the child being pulled to the ground and restrained and then they wonder why the child reacts to them.

Report comment

Yes Robert , you absolutely have shown me by your logical analysis how comprehensive are the dangers of “psychiatric professionals” and their “side effect laden chemical “drugs” delivered coercively, that cause a cut short lifetime of misery and dissatisfaction . People survive in spite of them (psychiatry, drugs, and the psychiatrists) not because of them. Anything that they do, perceived as being helpful by any human being , is better done by other means found outside the field of psychiatry which first do no harm . My confidence in writing this is strengthened by my own lived experience .

Your question , “And if not , what shall we do ?” I would answer like this > We must come to the place where we progressively boycott coercive psychiatry . At the same time we must promote the numerous first do no harm strategies that work described comprehensively and recommended by psych- survivors . We ourselves along the way must become our own doctors learning from psych-survivors , Traditional Naturopathy , energy healing systems like http://www.YuenMethod.com Homeopathy and others like Christopher Shade Phd. and Dr. Rau and his 80 member team at the Paracelsus Klinic , and there are more others to learn from, many who Blog and /or comment right here at Mad In America.

In this way a person can customize their own system to solve their own life problems without necessarily reinventing the wheel although sometimes creative invention will happen. Thank you for opening the floodgates of creative thinking . Fred

Report comment

Just a couple quick notes. In terms of using DSM language, my point here was to respond to Frances and Pies on their own terms: they have this diagnoses, and they say they understand that only a fraction of people with these diagnoses need antipsychotics for life. This is how they see it, and yet that have an evidence base for using the drugs that prevents them from using the drugs in the way they say they should be used. The point is to do an analysis from that perspective, on their own biological turf, so to speak. As for Kayla’s comment re the purpose of the website, in essence, yes, the founding principle of the website is that the existing drug-based paradigm of care has failed (in so many ways), and this website is supposed to be a gather spot for “rethinking” this entire domain of our lives.

Report comment

That’s what I meant for most effective points to crititisize. It’s plenty difficult enough with all of nonsense they throw in to distract. However, to argue the DSM at that point would be taking forever. Keep in mind Allen France’s is involved which would probably mean you would have to argue every addition, like it’s a separate entity. However, you seemed to have pointed to some things, that ought to make people at least, question if not doubt them. When it comes to questioning the DSM, there really had to plenty of space, to focus on just that. There really can’t be enough space dedicated.

Report comment

I worked with a guy once who was nicknamed “Sober Syd”. He was drunk every night and on the wagon every morning. Isn’t this prescisely what France and Pies are doing?

While they are on the wagon they present the evidence based position, but come 6 oclock its time for maybe one….. well okay a couple.

Good work Mr Whitaker.

Report comment

Once everyone knows there are no brain chemical imbalances, the legitimacy of psychiatry might also be in question.

“To distinguish himself from the doctor of divinity ( a religion), the doctor of medicine could not simply claim that he was protecting people from sin,” Szasz on “Mental illness: psychiatry’s phlogiston” http://jme.bmj.com/content/27/5/297.full

Report comment

The IL-legitimacy of psychiatry is NOT in question! >grin<

The pseudoscience of psychiatry is just as legitimate as any Mexican Drugs Cartel….

Mexican Drugs Cartels sell illegal drugs for huge profit$$$$….

Pharma & psychiatry sell *legal* drugs for HUGE profit$$$$….

There is NO real difference between the 2/

Report comment

I LOVE this discussion, and haven’t even read Whitaker’s whole piece carefully!

The LIES of the pseudoscience drug racket known as “psychiatry” are being quickly exposed.

The DSM is at best a catalog of billing codes.

We’re WINNING, people! KEEP UP THE GOOD WORK, ALL!…

Pies LIES, and Frances ain’t no saint!….

Report comment

This is a very helpful analysis, thanks Bob.

In the movie/book, the Big Short – Mark Twain is quoted; “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you in trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so”. The movie resonated w/ me in regards to this debate – the Big Short of Psychiatry. I hope to see the day when the willful blindness to evidence, the self-interested disinterest in facts will come crashing down. It’s interesting to me that Whitaker the journalist seems so much more engaged in true science than so many Psychiatrist/experts.

One other bogus pillar that is used to prop up the biopsych approach of carpet bombing/medicating anything labeled psychotic is the Duration of Untreated Psychosis (DUP). It creates this urgent rush to “treat” i.e medicate, as if delay is allowing a virulent wildfire to spread unimpeded. (B4Stage4). The sacred DUP is a key impetus & rationale to medicate early & not ask questions later. This must be challenged as well.

Report comment

Sorry, but this article disturbs me. It’s more than just using DSM language, it’s the way RW engages Pies and Frances in lengthy detail on their own terms, challenging their logic on what amounts to trifles, given the larger context of psychiatry not only passing around drugs and fraudulently “treating” so-called “diseases” which do not exist, but redefining problems which originate in cultural/political/economic structures as individual rather than collective ones.

At the end of that post, I set forth what I believe—again, based on the scientific literature—would be a “best use” protocol for prescribing antipsychotics:

Bob, does this not indicate you are agreeing that using literal drugs for metaphorical “diseases” and calling them “medications” is sometimes acceptable, and it’s just a matter of figuring out the optimal way of doing so?

I understand that some of this is probably meant as “devils advocate” type argumentation, i.e. saying “assuming what you say is correct…” then illustrating conflicts in the person’s own logic. But it’s hard to tell whether this is what is intended or not, as the bulk of the piece is written from the narrative of psychiatry, and seems more concerned with tweaking details than exposing the fraudulent underpinnings of psychiatric propaganda. The intended argument with Pies and Frances is unquestionably well-conducted, but seems as though it may have been written as a response to a challenge to “tell us what you would do,” when I think a better response would be not to engage them tit for tat on their terms and using their givens, but to expose such as a diversion from the bigger picture, which is not medical but political.

Report comment

“Bob, does this not indicate you are agreeing that using literal drugs for metaphorical “diseases” and calling them “medications” is sometimes acceptable, and it’s just a matter of figuring out the optimal way of doing so?”

I’m pretty sure he’s made it clear for a very long time that he’s done his best to separate his personal opinions from that of his interpretation of the scientific literature. If he were a guy just running around screaming his opinions through a bull-horn, nobody but his own would listen to him.

Report comment

To Oldhead and Jeffrey,

As Jeffrey says here, I don’t think my “opinions” about all this matter at all. I really come at this from this perspective: A medical specialty has a duty to be honest in its communications to the public. It has a duty to try to dig into its own science to best serve its “patients.” I think psychiatry has failed to meet that duty, and that is doing great harm. So much of my writing has been in describing how a look at the actual science doesn’t support the story that psychiatry has been telling the public, and that its story about the effectiveness of its drugs, particularly over the long term, is also belied by its own science. In essence, think of it this way: our society, i believe, has organized itself around a false “narrative of science” told by mainstream psychiatry, and my job, coming at this, at least in the beginning, from a traditionalist journalist’s perspective, is to reveal that falsehood to society.

I also don’t think this post is about a trifle, either. If you have Dr. Frances and Dr. Pies acknowledging that many “psychotic” patients shouldn’t be on antipsychotics long-term, then you open up a new discussion, about how its evidence base for antipsychotics is doing harm, and also, okay, then where is the evidence base showing that the medications provide a benefit for a certain subset of patients? Again, this post in essence is meant to reveal a falsehood: that science has shown that “psychotic” patients need to be treated with antipsychotics right away, and that such patients then need to be on such medications for life. It also leads to the point that Open Dialogue Therapy, in its selective use of antipsychotic drugs, isn’t actually doing anything radical, in terms of the scientific literature. The scientific literature actually argues for trying to minimize initial use and long-term use of the drugs in precisely the way that open dialogue protocols do.

Report comment

Yes, I understood was just having trouble wording clearly. Although, I could’ve sworn your tone of your writing, at least sounds like a blatant shadow of a doubt, whenever DX comes up.

I’ve spoken to many mental health workers, and to even have a conversation, it’s almost impossible. They will throw out terms, just because they Know people will take their word for it, because who can keep up with all of their jargon? Then you get them using all kinds of complicated sounding, unproveable things. If you point out it doesn’t make sense. The are either dumbing down something you can’t understand, talking from years of experience, talking for insurance companies, or you haven’t gone to medical school. Just to name a few.

What we need to do is come up with some clear critism of the DSM. Yes, that amoung other things. After, only reading a bit Bob’s words online, I was almost certain he did not believe in mental illness. Only I wondered why he would not say this, but I’d also heard that he was the cause of a lot of people getting, and taking people off medication, or not even going that root. I knew how difficult this problem would be to completely untangle, but their was progress. Although still there was some concern about the fact, he didn’t blatantly question DX. I thought there may be a reason. However, when learning about this site, I’m fairly confident that it’s the right move. Especially after seeing him put in to words, what was ounce jumbled up guesses in my head. However, I do want to try and explain this, even though my explanations seem to me to be just a less clear version of what Bob is saying, because I was so close to coming to that conclusion. In all honesty I may’ve even pressed further, and especially when it came to “selective” use of antipsychotics, even though I think we all know is code, for opting out of them whenever possible( In other words always in at least many of our opinions.)

However, I know it’s been suggested some kind of unified opinion, or voice. I think we need a unified plan. It’s so complex, and although it doesn’t have to be everyone agreeing all the time. I just think, that we somehow, have to get to the point where we understand where ther other is coming from to the point where we get distracted, and go in circles, on something we really agree in the end on. I also think we’ll have to go from different angles. If we are all making the exact same points, it will almost be impossible to cover everything. Some of us will also be better, at explaining, and implementing different things.

Report comment

I think Kayla and I may be having similar difficulty putting our fingers on some things that we sense but find it challenging to articulate. However there’s no confusion over the recognition that we’re all on the same side.

Let me reemphasize that Bob’s argumentation of the issue at hand is very thorough and convincing, for those who still need convincing.

Also, when I mentioned “trifles” I was not referring to or meaning to diminish the importance of the main point as expressed in the title. I was expressing a continuing frustration at the pressure to come up with the magical “perfect” argument that will finally “convince” those whose livelihood and self-image are based on their “professional” status that the foundations of the psychiatric behemoth are built on sand, in hopes that they will finally see the wisdom of our logic and lay down their privilege and power. Meanwhile those whose lives are being destroyed are supposed to stand by patiently waiting for them to have their epiphanies and agree to take their boots off our collective necks. In terms of the real damage being done 24-7 to real human beings, any intra-professional squabble over “treatment protocol” is a trifle indeed.

in response to a challenge from Frances, I set forth my “opinion” on what the scientific literature has to say about the long-term effects of antipsychotics. I think there is a history of science, stretching back 50 years, that tells of drugs that worsen long-term outcomes for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (in the aggregate.) At the end of that post, I set forth what I believe—again, based on the scientific literature—would be a “best use” protocol for prescribing antipsychotics

Sorry to sound like a persnickety pain in the ass, but this feels like a slippery slope, and perhaps even a ploy on Frances’ part to draw RW into his fold so that he can later say “Bob & I agree on X” (when maybe all Bob is agreeing to is that based on Frances’ reasoning the next logical step might be X). Not that I would expect him to fall for this, but Frances’ seeming desire to get RW to be “honorary shrink” in the effort to restructure (rather than undermine) psychiatry is noteworthy. So I do get nervous when too much argumentation takes place within the psychiatric narrative, even when there may be an underlying motive to give them enough rope to hang themselves.

Still, I find the above quote confusing, and putting “opinions” in quotes makes it more so. I take it that Bob means that his objective review of official “research” leads him to posit that, were we really dealing with science, certain conclusions would be inevitable, hence not “opinions” but facts. But since we’re dealing with propaganda, not science, where does that leave things?

Finally, I’m reading more about “Open Dialogue” (“TM”) here all the time, and lately it seems like MIA may be on the verge of officially endorsing it as an “alternative” to psychiatry or something. Anyway, I think that would be a bad precedent; even though I have no particular issue with much of it, it remains, as someone else mentioned, a “treatment program.”

Report comment

There were two ways, it seems, to respond to what Drs. Francis and Pies have recently written. Recognize the possibility that we can come together in a better approach or to bash them for not coming around enough. Obviously, bashing psychiatrists won out, shades of our Presidential candidates scapegoating others.

Report comment

So Stevie, what is your ideal way of coming together so that this mom’s experience doesn’t keep reoccurring?

http://www.madinamerica.com/2016/03/all-for-the-best-of-the-patient/

In case you didn’t read the column, her daughter died due to severe overdrugging in a psych hospital. And by the way, this is not an isolated incident.

Actually, this would be a good question for any psychiatrist visiting this blog who thinks we all ought to moderate our views.

And by the way Stevie, maybe if you and your colleagues would express your outrage at the abuses instead of just continuing to defend psychiatry, you would get more respect. But you keep ignoring this and acting like it doesn’t happen.

Finally, I am going to repeat a point that I have made previously on this blog that may sound extreme but I think is appropriate. Since commentators on this blog had horrific experiences with psychiatry, asking them to moderate their views is like asking rape victims not to be so angry. They have ever right to feel the way they do and to be heard.

Report comment

I was going to respond to Stevie but you did an excellent job of taking care of it. When are they going to realize that slave owners didn’t decide to free their human captives until they were forced to free them? We could wait until Doomsday for the wonderful psychiatrists to sit down and have a collaborative discussion with us but it’s never going to happen. They have no use for us. And I can’t believe that this person is defending someone like Frances who was in cahoots with Johnson and Johnson to promote Risperdal. How dare Frances stand there and act like he’s some knight in shining armor come to save the day. What hypocrisy. Anyway, I got started anyway didn’t I?

Report comment

Stevie,

I am almost amused by your characterizing responses here as “bashing” these psychiatrists. I could get heavily into bashing mode as an eye witness , insider — and am almost tempted to *go there* just to show you what actual bashing looks like.–

Instead, I would ask you to consider that neither of these psychiatrists spends much time in the company of the people they claim to be so concerned about. The evidence of their concern? Well, they label these *patients*, severely mental ill. That’s the extreme condition of a yet to be proven “illness”. So, while a bit of harm can come to anyone who is treated by way of medicine for a set of symptoms that have yet to be classified or studies as a *disease*, think about going full tilt with the most powerful drugs in your arsenal against — a set of symptoms that have yet to be classified, or identified scientifically as a *disease*. Do you see how the potential for greater harm is inherent in their pitch for attention to the *severely* mental ill? This may have escaped your attention– but it has profound significance to someone like me, who has experience, knowledge/training in the real medical model approach to real illnesses.

I dunno— what your analogy to the Presidential candidates means– but I see some commonalities in terms of denouncing the methods and madness of Donald Trump and the strong responses here to abject arrogance and disregard for the consequences of tyrannical approaches to *leadership*.

Actually, there is something very troubling about applying the concept of *coming together* , to two members of psychiatry, notorious for disregarding any opinion but their own. The better approach, imo, would be to check in with Frances and Pies when they are about halfway through serving their prison terms.

Report comment

Good to have some balance. 🙂

“we can come together in a better approach or to bash them for not coming around enough”

This naively presupposes that “they” and “we” have the same basic motivations, goals and values. Generally you don’t “come together” with your oppressor, at least until the conflict is resolved; you either overcome him or surrender to him.

Report comment

As a ~45-year survivor of the lies of the pseudoscience drugs racket of psychiatry, I believe that I know EXACTLY what you’re doing here, Mr. Whitaker, and you have my deepest and profound respect, and support. And I’ve so far only SKIMMED your work, above. It deserves more time than I have, right now. And, “oldhead” is just that. An angry old pothead who would argue with his own Mother, if she used the wrong buzzword. But ya’ gotta love him. He means well. His heart’s in the right place, but God only knows where his head’s at. And me, I’m all over the place in my writings, but I’m CRYSTAL CLEAR in reading comprehension….YOU Da’ *MAN*, Mr. Whitaker! GO, MAN!, go!….

Report comment

I know I shouldn’t respond to that but what the hell: 🙂

— For the record, I certainly would and do argue with my mother on occasion, it keeps both of us alive and real;

— The origin of my internet moniker is not what you assume (try google) (look up “irony” while you’re at it) (and maybe “projection”);

— If you’re interested in where my head’s at try my comment history, it’s pretty voluminous;

— Try to do more than skim the article and the responses and you might have more of a clue as to the issues and nuances being discussed.

To all: I promise not to divert or threaten the integrity of this thread by responding further to any of the above.

Report comment

*MOI*?……I feel like Miss Piggy…..”oldhead” actually responded to me?….Moi?…..

> rotflmfao <

OOoooo all: I promise not to divert or threaten the integrity of this thread by responding further to any of the above.

~aka: "medicinehorse179"/ Ditto/

Makes ya' **THINK**, don't it?

Moi luvs U 2, "oldhead"…..

Report comment

Bradford, almost everyone here is in agreement. You often times make great points, and I hadn’t said before, but the sites you told me about were very helpful. I’m very impressed with you, and many others here. While, I think you are right, I think what Oldhead brings up is very important. I, know I’ve underestimated psychiatry. Even if I believe Bob knows what he is doing, and even seems like it may be the smartest way to go about. It certainly gives me comfort that there are stil people trying to make sure, we’re going in the direction we all agree on. That’s what counts, and think we all know that, however think people’s defensiveness for Bob, may make them unable to hear this message. Those of us concerned still, think he’s great, and I even have a feeling this may be the way to go. However, it’s still a good discussion to have. Besides, what we really should be focussed on is what Allen Frances, and Ronald Pies. Also some commenters who critisize his overall message.

Report comment

I think the whole thing about “censorship” is bs anyway, I think what he means is people don’t buy what he’s selling.

Report comment

Damn, that comment was in reference to BDPT’s response to “therapy first” not a reply to Kayla. Sorry.

Report comment

It is BS indeed.

Report comment

At his blog, he mentions his comment here at MiA taking 36 hours to be posted. I assume that’s what he’s referring to by censorship.

Report comment

Joel might be disappointed to learn that the delay had nothing to do with a conspiracy to suppress dissenting viewpoints, but was simply a matter of the “editorial woman” (as he put it) being busy that day.

Report comment

@Kayla — Thing is, I don’t even see anything critical of RW in my above posts. I criticize the prevailing assumption by many that we are ignored by the system because we haven’t come up with the “right” arguments. I also question exactly what Bob means by some of his phraseology which is unclear to me and express some tactical reservations about engaging with “friendly” psychiatrists. All these issues go beyond Bob W. personally, and anyway I never accused him of being incorrect in his approach; there’s nothing to be “defensive” about on his behalf as there’s no attack in the first place.

Those of us concerned still, think he’s great, and I even have a feeling this may be the way to go. However, it’s still a good discussion to have.

I would just add that there’s more than one “way to go”; we all contribute to this struggle from different perspectives and have different skills to add to the mix. One doesn’t have to negate the other.

Report comment

I didn’t see it as critism towards him, but I was trying to bring the attention somewhat to people who actually critisize. I was just trying to show that everyone who was questioning the terms is still on the same side.

Deffinatley, agreed. I was trying to say that when I said, it’s such a complex, and difficult situation. The problems, are deep and vast. The solution would take all of us contributing in the best way we can. Think this is important. Also I meant the discussion to be around that, so instead of butting heads, and people deffending Bob, when I think he knows we agree with what matters. We could discuss how we can best out our unique takes on this , in the most effective way, and maybe avoid time spent on misunderstandings like these.

I mentioned in that post that Bob’s website already allowed this, and I felt like it was part of the plan. He’d responded, but won’t go into it, as it’s easy to locate, and I think most will know which one I’m talking about. However, it confirms my thoughts.

I think we should discuss, our concerns, and chances are it’s best for Bob to continue like this. Although, we can still voice our concern. In the mean time I think there should be a discussion of sorts, and a plan. Not “one voice”, but how each of ours can contribute, the best way in a collaborative sense.

Report comment

I might argue with you, sometimes, “oldhead”, and even use some, uh, oh, I don’t know – “dirty words”, – or something – but you know I love you. I promise not to make you read MY comment history, if you’ll forgive me for thinking I don’t need to read yours…. I know where you’re coming from, by reading the words you write where you’re at,….Right? >*grin*<~B./

Report comment

Two points, one hypothetical, one per experience:

1. Hypothetical, I would bet Ronald Pies belongs to the APA and is one of their “emeritus” academicians, thus he can’t and won’t buck the APA bylines of “drugs are us” by those who belong to that corrupt and derelict organization. I don’t know about Allen Frances, but sense he does not belong. I don’t, left it in 1995, never looked back, and my blog is constantly critical of the APA. Don’t go there, other commenters…

2. You, Dr Whitaker, seem to frame issues in black-white/polarized terms, well, it defines who and what you are until proven otherwise. Every drug has a place, and every drug runs a risk of misuse. At the risk of outrage, yes, some second generation antipsychotic medications have saved and improved some peoples’ lives, and usually in limited and reduced dosage use over time.

Cue the 4 Ps of pharmacology that applies to every single medication that has been on the market throughout life, until extreme exceptions show up, and such exceptions are counted on 2 hands at best:

Promise, Panacea, Placebo, and Poison. Med A comes out for indication A, seems to have a legitimate impact, and gets approved. Then, per Panacea, the company with Dollar Signs as pupils sees multiple indications and overshoots the needs recklessly and cluelessly. Thus the following “Placebo” is not always solely about a sugar pill, but, older and more established meds that their pros and cons have been responsibly clarified, and then wonder why this new med A trumps the use of older drugs.