Some would say the drugs I take are “medications,” by definition, and something quite different from “street drugs.” In some ways this is true, mostly because I don’t have to commit an act defined as a crime to obtain them. But obtaining marijuana, for instance, or even “shrooms,” which is still a federal “crime,” involves no more than finding a source and paying money in exchange for the desired substance. That is exactly what I do when I obtain my drugs. The only difference is that my source is first the pusher known as a prescriber, and then the pusher known as the pharmacy (whose intimate link to Big Pharma companies needs no reiteration here).

The first drug I took, after my teenaged foray into cannabis, was Elavil which was essentially forced on me (by my fear of the consequences if I refused) at Yale New Haven hospital in 1971 when I had just turned 18. This did nothing for me except make me intolerably sleepy and cotton-mouthed. For three months, in the hospital, I remained as I was when I came in: almost mute, unsociable, hearing voices, paranoid, and in extreme distress. After a consultant was called in, I was then switched to an antipsychotic drug, so-called — a phenothiazine. What I remember of this switch is that I quite suddenly began to talk, even talk too much, which scared me. They also instituted a behavioral modification program, which they told me I had to follow if I wanted to avoid being sent to a long-term hospital. After five long months on a unit where the average stay was 3-4 weeks, I was finally discharged, never having been told my “diagnosis.” If you were there, they presumed you “needed” to be there, no questions asked.

Some years later, attending medical school, I found that a problem that had assailed me first in high school and then throughout college continued to plague me: sleepiness whenever I sat down to either listen to a lecture or read or study. At Brown I had dealt with this by taking many long walks each day, followed by an attempt to study, which induced my falling asleep minutes later. When I came to, invariably folded uncomfortably over my books in the carrel and unrefreshed, I would go out for another walk, in order to “wake myself up,” and the cycle would start again.

This sufficed in college, but medical school was a different story, because we were required to sit through lectures for four hours each morning, with attendance at labs in the afternoon. My somnolence “started” the very first morning of classes, when I conked out within the first half hour and slept through the entire morning’s worth of lectures. I acquired a reputation for being “bored” and eventually photographs of me sleeping were published in our student newsletter, captioned with such words as, “Rip Van Winkle, it’s time to wake up!”

Desperate to stay awake, I saw the student health doctor, who took a history and suggested I had narcolepsy. Even though she wanted me to see a neurologist, it turned out he refused to see me, claiming I was faking sleepiness in order to get stimulants. It did not occur to me at the time that I could have simply seen another doctor and made a case for myself.

I was not happy in medical school and did not end up staying past the second year, for complicated reasons including the fact that I heard voices almost constantly, voices that instructed me to harm myself and which I obeyed. These voices had started many years before, but I had managed with them, if poorly. In fact, I was hospitalized during med school, something that seemed to initiate a proverbial revolving door of admission after admission.

Because of voices-induced episodes of self-destructive behavior, I found myself at Hartford Hospital in the late 70s. I was not given drugs at the time, as I recall, though I had variously been prescribed as an outpatient such “treatments” as Thorazine, Trilafon and Ritalin. I complained to the resident of new, visual hallucinations, such as scenes of battleships on my chest. Concerned, she had me tested. During a lengthy examination, some of which took place when I was asleep, I experienced what the diagnosing neurologist said were all four of the major symptoms of narcolepsy. He told me he recommended Ritalin, and that if any doctor subsequently refused to prescribe it, I could call upon him. And wasn’t that wonderful because I could now continue my medical school career, knowing Ritalin was all that I’d ever needed in order to function?

While I was elated to learn that narcolepsy had caused my sleepiness and that there was an effective treatment, the notion that he expected me to return to medical school made my heart sink. I knew that med school had been a big mistake. I did not want to return and in fact I never did.

Fast forward many years, and many hospitalizations and drugs later. It was the early 90s and I had been on Prolixin injections for “chronic paranoid schizophrenia” for an extended period, plus low-dose Ritalin for my chronic sleepiness. The nurse-practitioner/therapist I saw at the local public clinic, which was the only choice I had on Medicaid, decided I should try the new drug that had just come out, olanzapine, brand name Zyprexa. By this time, I had been prescribed almost every drug available in that class, including Clozaril, to which I twice had a potentially fatal reaction. While I acceded to the therapist’s request and started taking the new pill, I did not expect positive effects. Instead, I dreaded the dulling and deadening I had learned to expect from all the so-called antipsychotics.

A week later, I woke up one morning and opened a magazine someone had left in my apartment, The Nation as it turned out. I read and read until I finished the entire issue. Then I picked up The Atlantic Monthly and did the same. This astonished me as reading and staying awake had been a problem for decades. Despite my narcolepsy diagnosis, I always suspected that a terminal boredom caused my sleepiness. But suddenly, and mysteriously, I felt alive and enlivened, I felt in fact as if I had only just then discovered that life was worth living. I felt awake.

On Zyprexa I continued to read without difficulty for the first time since childhood. I devoured everything I could get my hands on, becoming particularly enamored of memoirs by Chinese women describing life during the Cultural Revolution. Much to my distress, however, I also ate too much because of an increased appetite that was clearly drug-induced. I gained a lot of weight in a very short amount of time. At my highest I weighed nearly 180 pounds. This was far more than I had ever weighed and much more than I was happy with. For years, however, I accepted what the docs called a “trade-off” and took Zyprexa as well as my dose of Ritalin religiously, overjoyed to be able to read and even for the first time pay attention to movies and public television.

The increased weight inevitably became a problem for me, however. When one doctor described me, someone who had always been on the thin side, as “obese,” I had had enough. I stopped taking the Zyprexa not just once but innumerable times, and invariably ended up in the hospital, refusing the drug for fear of gaining more weight. It was a nearly impossible dilemma, because in fact except for my hugely increased and uncontrollable appetite, I really wanted to take it.

Then one day the psychiatrist suggested I try yet another newly developed “antipsychotic,” Abilify. I felt I had little to lose, so I went home with a new prescription. I felt both better almost immediately, and I felt worse. While the new drug did help me be more alert, it also had very distressing “side” effects, making me irritable and causing nearly unbearable akathisia. Reluctant to have me stop it so quickly, the doctor added Geodon, which was supposed to be more sedating. To the surprise, I think, of both of us, this seemed to resolve the worst problems.

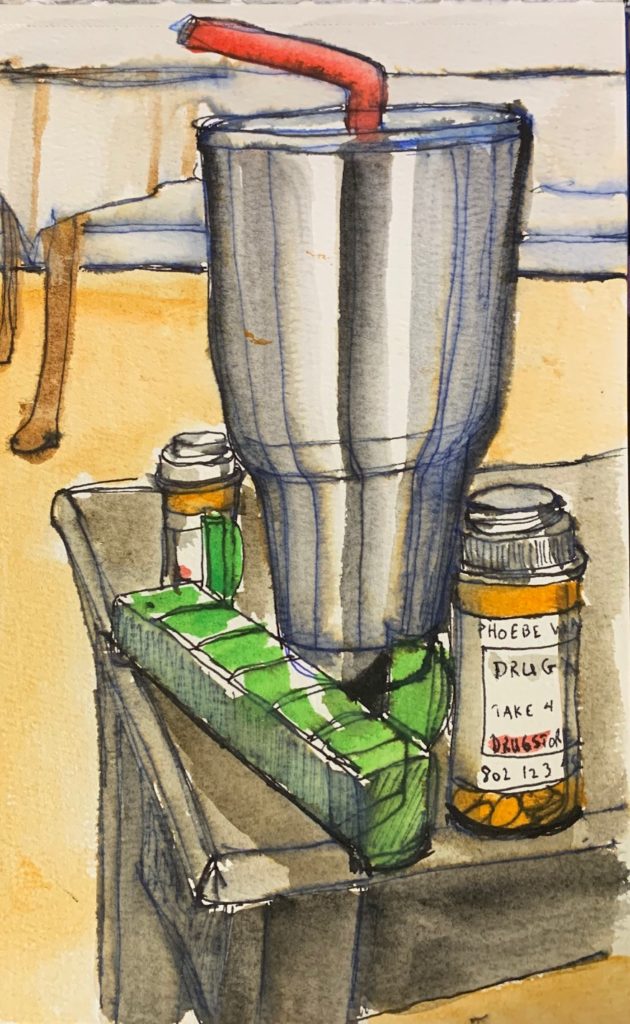

I had called Zyprexa the “intake drug,” because while I ate a lot on it, I could also take in books and movies, gobbling down such fare just as I did food. But on Abilify and Geodon, something different happened. I found myself writing prolifically and then doing art almost as uncontrollably as I had eaten on Zyprexa. I nicknamed the new two-drug combo my “output” cocktail. Though still hearing voices, life slowly began to improve. This was not a direct or linear progression, as I was still often hospitalized. But doing art became my be-all and end-all in life, and no matter how many other drugs I tried, I always went back to the Abilify/Geodon/Ritalin combo. Whenever I attempted to wean myself off all drugs, especially the “antipsychotics,” I found myself unable even to start a piece of art, let alone finish it. When I resumed taking the drugs, lo and behold my ability to do art would return as well.

Now, I suspect some readers might claim that it was the stimulant which helped me produce art and read. I would be the last person to claim that Ritalin does not have the effect of increasing one’s sense of well-being. But whenever I was on just the Ritalin alone, I stopped being able either to read (off Zyprexa) or to do art (off Abilify/Geodon). I went through many attempts to wean myself, but invariably the loss of my ability to do art brought me to the place where I went back on them. And that is where I am today.

Despite their category, I do not claim that this two-drug combo functions as an “antipsychotic.” Not at all. My voices may have hugely diminished now, but this is largely, I believe, because of a therapist, a guide, who has listened to me, heard my stories of lifelong trauma and helped me deal with this. She also “treated” me with what I can only call unconditional acceptance, even love, and that was the most healing of all. I doubt the voices or a lifelong susceptibility to “paranoid” fears would return even if I stopped taking these “antipsychotics.” Yet I remain on them and I want to remain on them. I have tried to stop taking them and always, always, no matter how slowly I wean myself, I stop doing art, and as a result of this become deeply suicidal. Art is my life, and my life is art. That’s the tag line I gave my second WordPress blog, Arteveryday365.com, when I started it two years ago. And without an ability to do art and to love doing it, my life feels empty and worthless.

Reading Robert Whitaker’s books around the time I switched to the “output” drugs was both eye opening and life-changing. I trust the results of his and others’ research. I suspect that “antipsychotic drugs” have few anti-psychotic effects, beyond the general dulling they induce, and I also suspect that for most people they do more harm than good. I do not believe the dopamine hypothesis was ever more than a lie, constructed to excuse the forcible drugging of many, including me. For decades, hospitals tortured me physically and psychologically. To this day my memories of having been restrained for days at a time, secluded for weeks, or given ECT by force can torment me, if I let them have free rein. But I have not been hospitalized in three years, going on four, and best of all, I can do art and be productive in a way that is life-serving.

I no longer make any distinction between street drugs and the ones I take. I know what helps me and I remain aware of both the risks long-term and the presence of certain “side” effects. But overall, the effects are more beneficial to me than harmful. I also think most people know what helps them and what does not, even when it is a matter of street drugs. A system that stigmatizes the “drug user” by criminalizing her or him helps no one. Indeed, as is the case with “shrooms” at present and with heroin in the past, it is likely true that many street drugs could be prescribed and used in ways that prove beneficial, if only it were legal to do so. However, since researchers cannot freely study these substances it is difficult to know. All I know is that I am neither better nor worse than those who take marijuana or psilocybin or illegal substances of other sorts. If the drugs I am prescribed did not benefit me overall, and in ways that others as well as I myself notice, care about and celebrate, believe me, I would no more take them willingly than I would swallow rat poison.

“I also think most people know what helps them and what does not”

Thank you for sharing your story, Phoebe. I too think that most people know what helps them and what doesn’t.

Report comment

I don’t think that people always know what’s best for them. Although I am totally against psychotropics I am also against drugs that alter the brain. I’ve seen too many clients( former substance abuse counselor) die from substance abuse, clients who believe they know what’s best for them. My family member who is addicted to heroin has track marks and abscesses all over his arm, we are waiting for him to get his tests from the health department which he’s known he needed to get for months but has not, has been in and out of jail, he dropped out of college at 19 and he’s very bright, he’s missed most holidays, stolen from his father, has broken the hearts of his mother and grandmother- the two people who are still there for him but can’t seem to help even though thousands have been spent on the best treatment facilities and his care. Watching someone you love more than anything systematically destroy themselves bc of an opiate addiction is horrific and I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy. The family is aware of past traumas and have paid for therapists and have never forced psychotropics- we hate them. We have offered to get him into any kind of hobby that may bring back that spark of life into him or motivate him. Help him have some kind of purpose but the addiction is too great and until HE get sick and tired of being sick and tired no one can help him. This article is irresponsible. As someone who has watched the masses believe everything they see on tv instead of thinking for themselves this article is just another tool to breakdown our families and society as a whole. I’m very very sad…

Report comment

I don’t think that everyone knows what is good for themselves, not by a long shot. What I do believe is that everyone has a right to make his/her own decisions, and the job of a helper is to assist that person in gaining sufficient perspective to see the options available and the likely consequences of whatever decision they make. Forcing someone to do something “for their own good” is so fraught with problems that it is far better to decide never to force someone to do anything at all in the name of helping. Sometimes we do need to use force to keep them from hurting someone else, but at that point, we’re helping the potential victim, not the person we’re using force on.

It is very painful to watch someone doing things you know will lead to pain, but everyone has to learn in their own way. We can provide information, show love, set boundaries, share perspectives, but in the end, each person is responsible for charting their own course in life, even if we don’t like the results.

Report comment

“Sometimes we do need to use force to keep them from hurting someone else, but at that point, we’re helping the potential victim, not the person we’re using force on.”

Excellent point, Steve. But why are our “mental health” workers deluding everyone, seemingly also themselves, into believing forced psychiatric treatment benefits those who are force treated?

And, for goodness sake, the medical community is force treating innocent people, merely because the doctors want to proactively cover up their malpractice, to prevent a legitimate malpractice suit, even when the person isn’t planning to sue for malpractice.

Report comment

People have the right to act stupid and make mistakes.

A major mistake a lot of moms make is protecting kids from taking risks/making dumb mistakes. How else can they learn and grow up?

Report comment

Look into the results Portugal has had after legalizing all drugs. I think the heroin problem in this country stems from the war on drugs more than anything.

Report comment

“I don’t think that people always know what’s best for them.”

We totally agree. I don’t think that people always know what’s best for them. As Steve said, not by a long shot.

In terms of which treatments a particular patient finds therapeutic however, I think the individual is absolutely the first and best authority of what they think helps and what they think does not.

I’ve witnessed anosognosia caused by a stroke. Very very few people in the depths of a crisis fit the medical definition for such. Patients complaining of severe side effects, or saying their medications don’t seem to help them, or would prefer “psychosis” over total numbing should be trusted as the first and best authority on themselves. Knowing what works for you in terms of “mental health” “treatments” is not the same as knowing what’s best in any broad or general sense. Driving people to suicide because we don’t listen to them is kind of counter productive, no?

As for myself, I was also similarly prolific art-wise while on a similar combination of meds. For me it was Seroquel and Concerta. Most of my paintings are dated from 2008-2010. I miss it surely. But my creative side is now expressed in writing. And I can math and science and logic again, which I just couldn’t do on the medications.

It presents an interesting dillema. Do I acknowledge deeply depressive tendencies and console myself with a deep dive into quantum physics or do I drug myself into a creative stupor. Clearly the author can still express herself well even while drugged to a state she prefers. But for me, language and logical expression were the trade off for my creative abilities and fewer depressive symptoms.

But just as she is free to make that choice for herself, so am I to say it’s not for me but good for her. I’ll still lobby for new prescriptions of these meds to be banned even while I support the decision of people currently taking them to continue.

There is a lot more nuance to consider than just whether someone knows what’s best for them. Because unless they’re having a stroke or so disconnected from our plane that they’re harming others, we should generally trust people to know what works for them and stop worrying about whether or not they do what we think is “best” for them.

Report comment

Very well said, KS!

Report comment

Hi Kindred spirit, thank you for your insightful and informative comment.

I was a writer (3 published book) for many many years, but I would say that much of that time I wrote in spite of the terrible anti-psychotics I was on. Only when I was switched to Abilify and Geodon did writing very suddenly come without fighting thru a drugged haze. I used to go to my writers’ group and say, “well, I wrote a lot this week, but that is only because I had help from these drugs.” I even thought that they could help other struggling writers. Then I fell in love with art, and while my desire to write has fallen off, my urge to produce art has not. People change and I think I grew sick of writing things — that is to say, poems — that few people in this country care about in general. My memoir, the one I wrote with my twin sister, is and was widely read, yes, but poems? Americans by and large have no patience for poetry, even though I frankly started writing poems because it was all I could do, since larger longer pieces were beyond my capability on the drugs I took in the 80s and 90s.

I am of course aware acutely aware of the dangers in taking these drugs. But most people don’t begrudge or judge others who have wine with each dinner. I try to think of my drugs like that. Something that for others might be “harmful” but overall is for me a life saver not a life killer. After all, how helpful is a drug-free life if it ends in suicide?

None of us survive our lives, frankly. I’m happy where I am now, able to produce art and also to study French with an absolute passion. What more could I ask?

Report comment

I used to be against anything that could alter the brain until I discovered just how much the right one can help.

I have the trifecta of OCD, depression, and anxiety, mostly in a bit of a cycle. OCD triggers anxiety, anxiety triggers depression, depression triggers stronger OCD, over and over and over again. Therapy feels like I’m missing a rung on a ladder to success no matter what I do. Went through a bunch of trial and error with different kinds of psych meds with various bad side effects or basically no noticeable effect at all. Tried the SSRI Cipralex. Ho-ley socks, MAJOR difference! I mean, could be better, but at least with Cipralex, it was like I had a stepstool for therapy! Stuff stuck! I finally gained the ability to do my own therapy based on what worked there (because communication of what’s going on with therapists is not always easy on either side, but I got some new techniques that helped enough to adapt, so better than nothing)! So screw anyone who says they’re blanket no good.

I do realize that not everyone reacts the same way with every med and that it’s pretty much hit and miss finding something that does, and without trying to kill you, but if it works, it works. If you feel you aren’t getting the same effect you used to, change meds or try going off them, but under no circumstances go cold turkey without a hospitalization-worthy emergency IN an actual hospital! Not ideal nowadays, but better than rapid withdrawal…

I tried Abilify in concert with my Cipralex to see if I could improve further, and dang, what a difference! Definitely not sedating for me. I’ve never felt that awesome (though it IS a mood booster, so)! I literally cried in relief. Then I literally cried when I had to stop due to a pseudo-allergy that froze my bladder and bowel muscles. I actually considered going on permanent assistance for excretion, but I’m too lazy for the upkeep and they wouldn’t let me anyway, so… yeah I know it’s extreme, but when you have hope for the first time in your life and it gets ripped out from under you, you tend to be a bit desperate to get it back. Ah well, you can’t win ’em all…

Cipralex was great for over a decade, but then my weight refused to go down, even with all the stuff that worked before, and I was ready for a new round of hit and miss for a new med. So I got a referral to an adult psychiatrist (I wasn’t an adult the first time around at 17 and some months), gave her all my relevant documents, managed to explain to her what exactly I wanted from her, and made an appointment for two weeks later to give her time to look through my documentation and make a decision. Got prescribed Effexor XR, but you can’t start that right away, and not at the effective dose, so we discussed the type of weaning I wanted from Cipralex. I decided I wanted a window of time when I was not being affected by meds to see how I was normally (minus some rebound anxiety). She didn’t like that, but we went with it. Yeah… I quickly remembered why I was on the meds in the first place… I had forgotten all the old habits and neuroses I used to have that were a pain in the butt. And it turns out the Cipralex was killing my sex drive, which was perfectly fine by me tyvm, and now it was driving me up the wall. Such relief when I got the first effective dose… too bad the max dose, which is the most effective for me, makes my heart rate go too high. But the next dose down is good enough. Now it’s actually possible for me to ignore my compulsions entirely instead of just trying to pull away from them or distract myself or do workarounds. I’d gotten rid of most of them on Cipralex, but this last one is really stuck in there, and now I have hope it can finally go away! Once I manage to kick this one, I’ll ask for a milder med so I can start the process of getting off completely, if possible. I still have focus issues that none of the focus meds do anything for, or the therapy techniques, but this one does, sorta, so I might need to play around with some things if that doesn’t resolve after. Maybe CBD oil will be worth a shot (it’s legal now).

Point is, you can use meds as a last resort if you want, but don’t knock them entirely.

They do work. Just not the same for everyone.

Report comment

Antipsychotics have no similarities with real drugs at all. Moreover they can be called Antidrugs. This is their effect on the brain. Sedation is the only real effect of antipsychotics. And for this simple effect you have to pay an expensive price. I am not a God and do not know the real purpose of narcotic and psychedelic plants about which you write in your article, and easily compare them with cheap dangerous chemicals, produced by truly perverted minds. It’s like taking clonidine for sedation and putting yourself at risk of being bedridden, as a result of a stroke. And people still abuse clonidine without even knowing about the risks. And the doctors continue to prescribe it. The same can be said about antipsychotics. Also i found your comparison of antipsychotics with rat poison a little naive, because it is the same, literally, no jokes, no metaphors. You can even change the name of the article – “Why i take rat poison and don’t plan to stop.” Wouldn’t people think like that in 100 years? considering this rhetorical question and the subsequent answers to it a little wild?

Report comment

Actually antipsychotic drugs, so called, are not rat poison, though for all I know they could poison rats. Rat poison is usually an anticoagulant “rodenticide” like warfarin.

Report comment

Phoebe This is true! A long time ago, Puzzle ate some and we had to rush her to the vet. She ended up fine. We were lucky as rat poison can do some serious damage.

Report comment

Sedation is by far NOT the only effect of antipsychotics in general. These drugs can — I emphasize can — cause many many psychotropic effects, including the psychotic symptoms they claim to treat. These effects are as real as real can be, and what we call a “drug” versus a medication has much more to do with legality than with real or unreal effects.

Report comment

Tardive psychosis came with my experience on neuroleptics. i didn’t know that was a thing for decades. Doctors told me I didn’t know what I was talking about and it was just my “illness” talking when I tearfully told everyone ‘Antipsychotics make me psychotic.”

Report comment

They don’t sedate everyone. Psych meds affect everyone differently. Abilify was a mood booster for me, except it turns out I’m pseudo-allergic to it, so dang, but if it wasn’t for that, I’d still be on it.

Report comment

Phoebe, people try to manage their moods and waking and sleeping via chemicals. I think it is all fallacy.

We need to learn to manage ourselves, self regulate, more like a kind of yoga.

But the chemicals prevent us from being able to learn to do this. They take much, but they give nothing.

Report comment

Hi Pacific Dawn,

I’m not in disagreement necessarily although I do feel these particular chemicals did give me something. But what one person needs or decides voluntarily to put into her or his body should be up to them…I just don’t want anyone saying I have to take this that or another thing, OR because they disapprove, that I *cannot* take this that or the other thing. Otherwise if someone wants to self regulate with yoga, great! The more power to them. It’s just that mood altering chemicals and alcohol have been with mankind since the beginning and it is nobody’s business to judge me about what I or anyone else chooses to eat, drink or otherwise absorb.

Report comment

All hail Body Autonomy!

Report comment

Well we do have laws against some drugs, and then also laws which make some drugs by prescription only. You are free to speak out for changes in this, but does not mean that things will go that way.

Never in all human history has their been any society which has operated by the principles of Libertarianism. That is mostly just a way to propagate the doctrines of Social Darwinism. Its not a realistic or sincere political movement.

Peter Gøtzsche has said that it would be better if these drugs are off the market. I don’t think he is intending that they be offered as recreational or self-prescribed drugs.

We have plenty of things which work like that already.

Now regulation of such things has proved very difficult. But I for one would not think it wise to introduce even more chemical variations.

As I see it, chemicals might help you adjust to changing circumstances for like a day or two. But beyond that the chemicals are always taking more than they give. The benefit is illusory.

As long as we have such drugs in circulation, then people are going to be susceptible to the claims that doctors make, that the drugs are good for you. Until people learn to self regulate, drug free, then they will always be at risk. We can’t eradicate the knowledge of how to prepare the chemicals, even going back to ethanol, but we can help people learn how not to need them.

So we certainly are not going to be able to prohibit everything, but I don’t see any reason that we should be converting prescription drugs into self-prescribed drugs, at least not in most cases.

Report comment

Humans craved forms of ecstasy since before history. When alcohol was first developed, it was church controlled. Then there was prohibition by the state. Eventually, psychiatry got involved to a degree.

My point is that I think the ecstatic experience is a part of human nature, and will be with us always, and probably continue to be controlled to the detriment of those who crave the freedom to use chemicals to achieve it.

Report comment

Hi Phoebe, like you say mankind has been taking hallucinigating substances from the begining whose to say people like us who have these traits natirally have simply inherited them.

Basically it is for nobody to judge what helps us get by in life.

looking at your remarkable artwork and writing you have done the right thing for you. Stay free Phoebe Stay producing your wonderful work. You have done the right thing for you!

Report comment

Thank you so much for this supportive comment, Bippyone. Like most people I would much prefer not to need to take these chemicals, and I am well aware of the risks as well as the side effects. But I am glad at least at the age i am now, 66, to be relatively free to choose what I take and how. It was not always the case, esp in hospitals where if I refused an objectionable drug’ they would by court order forcibly inject me, most often with large daily doses of HALDOL, essentially as punishment. I no longer allow anyone to hospitalisé me and so this is no longer a problem. But if these two particular drugs were not easily obtainable, I am not sure what I would do…i have become deeply depressed and suicidal when off them, simply due to the all encompassing losses — of art and writing — that I incur. Thanks again for being so encouraging!

Report comment

Well said. Thank you so much. Bless you

Report comment

I believe each person is the authority on him/herself. We need to allow each other the space to make our own choices. I’ve been criticized for having a hard time getting off drugs to help me sleep. However, we aren’t all alike. I found out my body can’t make its own melatonin.

Access to information is vital. I keep wondering why the medical profession works hard to keep it from us.

Report comment

Hey Julie, I think the medical pros most likely are being paid to keep info from “the people” and they may believe it is for “our good” but it isn’t. Dr Google has helped a lot at least for those of us who know how to properly sift the junk science and medicine from the helpful info.

Phoebe

Report comment

With information in our hands, we are stronger and have less need to pay the doc!

Report comment

I’m sorry for your sleep troubles. I’ve suffered my entire life. For me I found sleep meds, over the counter or prescribed only created more issues in addition to affecting my liver. There is another way. I still don’t sleep well but I learned that I won’t die from it. I did learn that if I stayed awake all day even if I was up all night that I did get more sleep the following night. Over time, even if it doesn’t work the first couple nights your body will eventually fall into a rhythm and fall asleep. There are ways to calm the nerves without psychotropics or illicit drugs. I wish you only best and hope you find ways to cope. 🙂

Report comment

My troubles are not due to not being able to fall asleep but sleeping at odd hours…I can sleep 8 hours at night and still be very very sleepy all day no matter how much I’ve slept at night.

Report comment

That’s a common adverse effect of the neuroleptics.

Report comment

As I wrote in my essay, I have had narcolepsy since high school And possibly before then…I was not on neuroleptics continually until I was 30.

I’m not saying that neuroleptic drugs do not cause sleepiness, and they have certainly exacerbated mine — walking around on 1500mg of Thorazine (as an outpatient!) plus 1000 mg of Mellaril most certainly drugged me into oblivion. Clozaril too I found immensely and horribly sedating. But my sleepiness started well before any neuroleptic therapy. Well before it.

Report comment

Animals don’t eat antipsychotics.

Report comment

They are smart!

Report comment

Not unless they are part of human experiments, experiments that show that neuroleptics eat their brains.

Doctors love patients who sell their products. I got a terrible case of akathisia on the Thorazine I received the first time I was “hospitalized”. That was enough. The effects were not such as would encourage artistry, but I’m glad you found some way to produce regardless. I’ve been on Zyprexa, too, and I know the effects can be more bearable, but this in itself I find deceptively dangerous. I would think Abilify is more of the same, that is, potentially bad for your overall physical (i.e. real) health in one way or another. I just have a problem seeing people who should be relatively healthy moving about on walkers or in wheelchairs. I just feel, all told, you have to watch out for the reefs.

Report comment

thanks phoebe…we are not all the same…

each person is different…whatever twirls your turban..

Report comment

Phoebe

This was a well told story of your complicated relationship with psychiatric drugs. It is a very sobering and pragmatic assessment of this relationship, and you do not seem to buy into psychiatry’s “chemical imbalance” theory or overly romanticize the benefits of these drugs.

What is missing for many readers is a more in depth understanding of the connection of your history of psychological distress and your history of trauma. There is only one brief mention of you working on trauma issues in therapy.

Without some understanding of (and a more in depth presentation) of the environmental factors that may have led to your distress and difficulty focusing and completing important tasks in life, people are left to speculation as to what are the causative factors for these problems. And if a trauma history was, in fact, a central factor in the onset of your difficult struggles in life, what kinds of trauma help (“treatment”) is actually effective and can (in some instances) mitigate the necessity to rely on mind altering drugs as means to coping with a troubled world.

Of course, a trauma narrative is a deeply personal thing, and you are under no obligation to share this story in your blog, nor am I suggesting you do so. I am only suggesting that it is difficult for readers to reconcile all these complex issues and compromises related to taking psychiatric drugs without knowing essential details of the overall narrative, including what forms of trauma help was accessed (or not accessed), and what was most helpful.

I admire how much you have accomplished in life and your resilience in the face of such enormous obstacles presented by a very harmful Disease/Drug based Medical Model that dominates the “mental health” system. Thank you for sharing this story.

Richard

Report comment

Hi Richard,

Yes I appreciate the role of trauma…it was mostly that I needed to stick to one subject and not meander all over the place…also constrained by word limit. But I also think if I had not felt obliged to go to med school and could have “discovered” art and my abilities before age 55 I might have lived better. No regrets, tho. I learned a lot along the way, and painful experiences teach much.

Phoebe

Report comment

This is the essence of a drug-centered approach to psychopharmacology. It is neither anti- or pro- drug but encourages a full understanding of a drug’s psychoactive effects, does not assume the drug is treating or correcting an underlying disorder, and encourages each person to sort out what is most beneficial.

Thanks for this essay.

Report comment

Hi Sandy,

Thank you. The drug centered approach is one I have favored for many years! Alas most docs feel a need to diagnose an illness and I doubt insurance companies would pay without it…

Phoebe

Report comment

thank you for sharing your experiences with these different drugs. My son is a newly diagnosed, newly medicated young man. I would love to think that he could manage himself as some others point out, but I don’t think he is capable at this point. He suffers from anosognosia, so having delusional disorder with absolutely no insight. Although I’m a nurse, I often feel like doctors are so quick to prescribe meds as a quick fix. For example, they really push antidepressants in lieu of encouraging exercise first. I think meds serve their purpose in many cases, but often they are overprescribed. I feel guilty because I felt like my son absolutely needs to be on meds. He is doing so much better, BUT he is very sleepy & his reflexes are just much slower. Only on meds for 3 months so I know it may improve a little. My question is, what advice would you give to your younger self? I feel like I’m making these decisions for my son, because he isn’t capable. I don’t want to make bad decisions for him, I don’t want to have regrets. Loaded question, I know.

Report comment

If you’ve put your son on the antipsychotics, please see my comment below.

Report comment

Anosognosia, in my opinion, is only a doctor saying that if the patient doesn’t agree with him or her that is a symptom. In my book, denying that you have an illness is a sign of health! After all, as you might know if you have read in MIA widely, there is absolutely no proof that such things as mental illness esp as diagnosed by a doctor, even exist. If these are actual illnesses, where is the anatomical, neurochemical or physiological problem or imbalance? No evidence shows up in any blood test or scan, or anywhere else. And when it does, lo and behold one finds out it is not really a mental illness so called but a known physical illness.

I am sorry your son is suffering, if he is. But sometimes I felt that they were drugging me, forcibly and against my will or otherwise, simply because, well, as I put it, “to put me out of *their* misery”!

The important thing is not to rush into anything, many extreme states pass without intervention of the medical sort.

I’m sorry I can’t help you more than this. Partly it’s because of the hour, but partly because I don’t buy the medical model lie that mental suffering is an illness that must be eradicated Asap.

Phoebe

Report comment

my son said he was 100% fine. He also said he was the richest person in the world, the descendant of Putin, we were hiding his fortune. Because he thought he was rich, he didn’t need to work, wouldn’t eat most foods, definitely no food we prepared because he might be poisoned. He was becoming reclusive, pushed away most family & friends. The only person he was okay with was me, and only to an extent. We were 100% financially supporting him. Yes, I will admit, he was making me miserable. He would brow beat me daily about his money. He would always be here & never leave the house. I was heartbroken watching this ensue. He is now working, taking classes, eating, gained 15 lbs, socializing, visiting family. I don’t want or expect perfection. I just want my son to be happy & see if he can be self sufficient to some degree. Paying his bills, not doing anything, I felt I was enabling him. This has been going on for 5 years, btw. So for me and my husband, we felt the younger we try to get him help, the better chance he may have of living independently, being able to have relationships where he doesnt feel everyone is out to get him.

Report comment

But why focus on the lack of insight, which appears to be in the past according to what you write, when you are much happier with who he is today? Saying that someone lacks insight into their own health and well-being just says to me that we aren’t trying hard enough to see that there is always a thread of logic. So many people (I’m not saying you) spend too much time focusing on what is missing, rather than on working with what’s there.

Report comment

Rossa, the past was literally 2 months ago before meds & hospitalization. And his lack of insight was hindering his ability to hold a job, have friends, leave the house, pretty much do anything productive at all. I am all for people being drug free, if they are able to be 100% accountable for their actions, finances, etc. But my son was not only dependent on us fianancially, he also harrassed us daily wanting to know where is fortune was that he said we were hiding from him. So, I understand the argument of live & let live, focus on what is there, but what about getting a job, paying his own bills, having some independence? are these things I should not encourage & give up on? Because without the meds, he was going nowhere fast. I didn’t see how things were going to improve for him without the meds.

Report comment

I find this comment really interesting

Report comment

Tifftread, have you read Anatomy?

Report comment

I have not.

Report comment

Anatomy of an Epdemic by Robert Whitaker is an eye opening expose of many psychiatric “interventions” chief among them the use of psychotropic drugs. If your son was diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar I also highly highly recommend Whitaker’s MAD IN AMERICA book, the updated edition from maybe 2013. It is a fascinating and extremely disturbing account of how serious mental illness diagnoses have been treated in the US…right up to atypical antipsychotics, and their development. I hope you will look into these two books soon, before things are irreversible. My best to you,

Phoebe

Report comment

Tiff how does your son seem better? Are his odd behaviors and words lessened? Maybe his anxiety is better. I had short term benefits on the drug Stelazine at 6 mg for a few months.

I seemed better on psych “meds” to those around me because I was too tired/deadened to do or say anything weird. But i could never build an adult life for myself, wound up with OCD, couldn’t get along with others due to emotional numbness, have not been gainfully employed since my teens and was in low grade depression non-stop for over 15 years. Frequently suicidal.

I went off my “meds” without my family’s knowledge. Asked forgiveness rather than permission. Mom was shocked at how improved I am now, but my organizational skills and short term memory are horrible and may not improve much. Still, my OCD is gone along with extreme depression. I get along better with people when not exhausted from the iatrogenic disease I developed and am motivated to keep my room clean (despite aforementioned fatigue.)

Mom swears I used to need the “meds” though I was fully compliant during my freakiest episodes. The numbing out would make me do dumb things I never did before. Short term effects were way better than long term.

Report comment

Before the meds, he was unable to hold a job & thought we were holding his fortune against his will. He thought he was the descendant of Putin, he was a super hero, He was the richest person in the world. He was consumed with these thoughts that we were keeping something from him. He wasn’t leaving the house, isolating himself. Slowly but surely he had convinced himself that family members & friends were in on this & were against him. Did I want to my son on meds? No. I know the long term potential side effects & feel like it is a last resort. My son 100% refused to talk to anyone, he felt he was 100% fine. If he was happy in his own world & could support himself & his decisions, then I would be fine with NO meds. But I was 100% financially supporting him which I felt was just enabling him. We ended up having a therapist come to the house. He opened up to him some & agreed to be committed. Ended up on Invega injections. He is on his 3rd. He drove himself to his appointment last week unprompted. I do believe that he feels better on the meds. He is working, taking classes, socializing, visiting family that he had once blocked out. So I do feel thankful for the med at this point. I worry about long term. I would love to see him off the med & able to hold a job. Is this possible? I dont know. I only know what was happening before the med.

Report comment

The meds have their place, but I don’t like injections because I worry that they come in one size and one size only. Can people ask that the dosage be lowered, for example? Can people eventually wean off them? Clearly I don’t know enough about them. I just know that I’ve always cautioned my son to refuse them because they wrest control away from him and give it to the professionals.

Report comment

they started with a lower dose to make sure no adverse reactions. Then a follow up dose, then monthly maintenance. They told us that the dose can be adjusted &/or the doses can be spaced out further. I think everyone has a different story in what will work best for them. My son & I speak openly about potentially one day trying to be med free. This is very new for him, only 2 months on meds. I think it will be a process & see how he does. If he insists on coming off the med, that will ultimately be up to him. But he will have to own his decision whatever the case may be.

Report comment

Tiff, How did you find a therapist to come to your house? We would like to do this for a family member who won’t leave the house & stays in bed almost all day. So far we haven’t been able to find a therapist who will come to the house. Thanks for sharing your journey with your son.

Report comment

Rachel, also thank you so much for sharing your experience. I often wonder what my son is thinking, is he holding in all of these delusions that he had. Another thing I didn’t mention is that before meds, he thought he could be poisoned & would not eat much. The meds are obviously making him hungry & he no longer withholds eating. He has gained about 15 pounds, eats what we cook. I do believe his anxiety level is down. His energy levels have definitely picked up since the first month on the med. He vacationed with us last week & is just so quiet. I hate that the med may be suppressing his natural instincts & personality. It’s just such a double edged sword. As a parent, this has been my worst nightmare. To see your child struggling & not being able to reach them. I can only imagine how those suffering must feel.

Report comment

Are you familiar with the book “Natural Healing For Scizophrenia & Other Mental Disorders” by Eva Edelman? If not, it’s an excellent book. It gets into what medical / nutritional things to look for & rule out when it comes to “diagnoses”. (things like heavy metal poisoning and Celiac’s for symptoms of “schizophrenia”, for example). The allopathic/ conventional medicine approach often misses ruling certain things out. I highly recommend this book, as well as Craig Wagner’s “Onward Mental Health” website. Good luck to you & your son.

Report comment

I sought out psychiatric help because of some rough experiences. An awkward loner in my teens. Had felt there was something bad/wrong with me for a long time.

My dad was a clergyman who couldn’t keep a church for long. How long he stayed depended on how well his family members–as well as he–performed for the “right” people. Appearance was EVERYTHING. And we were watched ALL the time. I felt woefully inadequate.

2 years of sexualized bullying in high school made my anxiety worse than ever. (And made me loathe my body.)

Depressed and anxious as a college freshman I was afraid to leave my dorm room. Dr. M gave me Stelazine which took the edge off my anxiety. Unfortunately it made me sluggish, numb and the good effects wore off.

I mentioned I had negative thoughts that wouldn’t leave on a visit later. Dr. M put me on Anafranil. No sleep for 3 weeks. 23 years in the MH System as punishment for my bad reaction to a drug he put me on. (My sister is allergic to penicillin but no one suggested she be shamed and segregated forever.)

I would have told young me to 1. Get a driver’s license despite Mom’s protests. Can’t go car free in Indiana. 2. Drop out of the university and get a clerical job after a year at business school. A 4 year degree was my parents’ dream. Not mine. And they were dead wrong when they said it would help me find work. No MI history and a good work history are the ticket. I held several jobs in my teens and had a reputation as a conscientious worker. All ruined at age 20.

Report comment

I believe in psyche, not in drugs or psychiatry. Without the proper image of the psyche, people will think that psyche is some kind of brain illness. For monotheistic psychiatry, drugs are used, as a crucifix for a satan. The believe that psyche is some kind of demonic power. Psychiatry is Van Helsing and your psyche is a monster for them.

The problem is that psychiatry believes in drugs and mental health (apollonian ego fundamentalism). PSYCHiatry without psyche is a sin against humanity. Psychopathology is an enemy for their theological or rational believes. And psyche is not something which can be measured by science/ empiricism or theology. We should create the proper image of the psyche.

James Hillman ,”Re-Visioning psychology”

Mental health is just one of many kinds of perception.

Report comment

In reading your essay, I noted you spoke about having “forced ECT”, yet you do not seem to have suffered from cognitive or memory issues. How much ECT were you given and what type?

Do you recall how it did affect you?

Report comment

I have written extensively about my experience with ECT. You can read what I wrote here:

https://phoebesparrowwagner.com/2012/04/08/shock-treatment-ect-therapy-or-torture/

I suffered from symptoms I now attribute to ECT for years. But I would say that whatever losses I incurred, they have been largely ameliorated. Though I still lack many memories of that now distant past, I form and retain new ones just fine.

Report comment

You are lucky, then. Must have had unilateral. I lost 25 yrs of memories- completely gone and now can’t make of keep new memories, more distressing- 14 brain frying bilaterals.

Don’t know why they keep using brain damage as treatment…

Report comment

I had 18 sessions, some bilateral then switched to unilateral.

Report comment

Yes! We need more individual responsibility, not more expertise or even more science.

http://refusingpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2010/05/drugs-solved.html?m=0

Report comment

“Now, I suspect some readers might claim that it was the stimulant which helped me produce art and read.”

I, too, am an artist. I, too, was a “very prolific artist” while psychiatrically drugged. So much so, that the child abuse cover uppers of my former religion, who had me psychiatrically poisoned, to cover up the abuse of my child, are now terrified of my “too truthful,” “insightful,” and “prophetic” artwork.

Once I escaped the psychiatric system, in 2009, I will admit I did decrease my art production substantially. But, that was more due to the fact that the child abuse covering up religions have been utilizing the information age to have multiple corporations target certain families, as touched upon in the Preface of this book by a decent ELCA insider. I’d be one of the many “widows” mentioned in the Preface of this book.

https://www.amazon.com/Jesus-Culture-Wars-Reclaiming-Prayer/dp/1598868330

My family was eventually party to something like 40 class action law suits by thieving corporations, of which I have the physical evidence. My husband couldn’t handle the onslaught, and died at the unexpectedly young age of 46. $250,000 of my home equity, in my family’s home, was stolen from me by a bank that had neither the note, the assignment of our home to them, nor the mortgage. Because my family’s home had never been legally assigned to our “mortgage lender.” Even according to paperwork eventually sent to my family, by the company that actually had our mortgage, shortly after I short sold my families’ home in 2012. But since “all the Kane county judges are bought out by the banks,” according to many Kane county lawyers ….

During this entire time I was also working, trying to raise my children, while also researching into the psychiatric crimes that had been committed against me, all of which takes time. But this brings me to the point that your “beneficial” drug cocktail, a combination of antipsychotics, likely causes anticholinergic toxidrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

Anticholinergic toxidrome creates “psychosis” / “voices,” but it also makes people “hyperactive.” “Inactivity” is a symptom of “schizophrenia,” not “hyperactivity” or productivity. Anticholinergic toxidrome is what likely allows you to be very productive, rather than “inactive,” when psychiatrically poisoned (a toxidrome by definition is a poisoning).

I was anticholinergic toxidrome poisoned, too. But it does take time, and research to understand why weaning from the psychiatric drugs is wise. I’m not here to convince others they must do that. But I do recommend it. And i will say, I did have about a decade of dearth in my personal artwork production. But researching all the crimes that were being committed against my family, and trying to fight against such corporate crimes, was time consuming.

Plus I spent a tremendous amount of my creative inspiration, in running an art program for children, which of course does take creativity. But I’ve downsized the art program in the past year, and I have vastly increased my personal artwork production. So getting off the psych drugs, doesn’t in the long run, prevent inspiration for artists, at least in my personal experience.

Nonetheless, to take drugs or not, is a personal choice. But you should know your “beneficial” drug cocktail likely causes anticholinergic toxidrome, which is a medically known form of poisoning. But getting off the drugs is a challenging journey, as well.

For me, it merely took the form of a staggeringly serendipitous, song and dance, bike riding, home remodeling, “show me a garden bursting into life,” “manic” gardening “psychosis,” that eventually turned into a “born again” story. But it was also an awakening to my unconscious dreams. So a drug withdrawal induced “super sensitivity manic psychosis” would possibly be more difficult for someone with a personal trauma history.

God bless, and I hope this might more accurately explain both your “psychosis,” as well as your productivity on the antipsychotics.

Just curious, is your twin sister an identical or fraternal twin? And was she also diagnosed with “schizophrenia?” I’m curious since the psychiatrists are still fraudulently claiming their “serious DSM disorders” have “genetic” etiologies, despite having zero scientific evidence.

Report comment

I have a psychological label. These days life is complicated.

My home is here though it could also be there yes. Great one. So great ahhhh. I’m at Denny’s eating dinner. I feel like I can feel peoples brains especially people that scare me. It’s quite uncomfortable. I think of great things to keep me comfortable. This is just one specific instance of how this unbelievable thing they call psychosis gets all out of proportion. So many nuances and what not that makes people squirm or is it just me. These quirky yet very interesting abilities or obstacles are often dark yet really awesome basically.

Report comment

PatUSA,

You are correct, our homes can be anywhere.

We are just one huge collection of people, yet individual.

We can all sort of feel people’s energies, (their brains),

and it can be quite uncomfortable.

It’s good to be aware and know that it’s not odd.

Some people feel things more than others.

Report comment

Loved your essay Phoebe. I’m checking out your art site.

I find caffeine helped me create in the past. Now I have one cup mixed with half decaf each morning. Off psych drugs now I find more caffeine too stimulating. Used to drink 5-10 cups a day on “meds.” And still slept 10-12 hours out of 24.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Thanks, Phoebe, for your insightful, yet different MIA contribution.

Here is an artist you may not know about:

http://observer.com/2015/04/the-stunning-story-of-the-woman-who-is-the-worlds-most-popular-artist/

The Polka Dot Princess: Yayoi Kusama

At the time, she was second only to Andy Warhol, with her work based on seeing dots everywhere. She lives in a hospital in Japan with her studio nearby.

Report comment

Hi Don,

Yes I have read a lot about kusama. What I do not understand is why she chooses to live in a hospital. But be that as it may, she certainly has more freedom than most hospital patients! and probably a lot more money too. Perhaps she funds her own hospital life, I don’t know. No hospital I was in ever let me go out daily to a studio to paint, and usually monitored and severely restricted my access to art supplies. Maybe Kusama doesn’t like cooking and shopping for herself. I don’t either so if the life in hospital works for her, i say, the more power to her!

Report comment

I believe that psych drugs are not the only way to sedate or stimulate oneself. There are much safer, legal, and equally if not more effective methods. Few people realize that sedative herbs even exist. Valerian root, lavender, kava-kava, and motherwort work very well, if you find the right dose, and you can increase the dose severalfold without toxicity. I like valerian the most because it has no effect on mood; I need a triple dose three times a day for a good sedative effect (I am a pretty big man). Motherwort and lavender tend to get me high; you can combine them in various ways safely. Other good sedatives are a hot environment, excessive physical exercise, raw honey well diluted in water, and beath-holding exercises. It is worth noting that drug companies have sponsored a number of fake studies “showing” that valerian does not work, for obvious reasons. Apparently, they also helped to ban kava-kava in European countries. Valerian is much safer and cheaper and as effective as chemical sedatives, but currently you cannot advertise valerian as a treatment of insomnia or schizophrenia, and it is not included in the official treatment guidelines in the US.

Regarding stimulants, rhodiola and ginseng are pretty good, and the dose can be increased if needed. They are stronger than coffee and are more effective if combined with brief cardio exercise, e.g., on a stationary bike. Your pulse should double for 10-15 seconds if you want to see a real wakefulness-promoting effect. This combination does not have a strong effect on mood. If you add an adapted cold shower, then mood will increase sharply and you may become hypomanic. These treatments increase creativity and kill boredom in my experience (but this combination increases impulsivity and other symptoms of hypomania). Of course, you need to familiarize yourself with the contraindications of the above-mentioned herbs.

As for hallucinations, I don’t believe any drugs can treat them (I never had them myself, but I have talked to the patients and read various studies). There is no reason to believe that sedation will reduce halluciations if there is no concurrent agitation. In my opinion, what one needs is to heal the brain by making many changes toward a healthier lifestyle: add small amounts of vitamin-rich foods, not pills (cod liver, beef liver, seaweeds, turmeric, black seed, a glass of raw pomegranate juice, etc.), try a week or two of a 100% raw diet (pascalized raw meat is safe), try brief fasting regularly, exercise was mentioned, a makeover of the intestinal microbiota, hot baths or sauna (don’t stand there to prevent varicose veins), hyperventilation exercises, brief tanning sessions, etc. There are some case reports showing that a ketogenic diet can cure schizophrenia.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19245705

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26547882

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23030231

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14283310

Report comment

If any of that stuff worked on enough people, Pharma would be extracting the responsible chemicals and marketing them faster than you could blink. How do you think they come up with new drugs to begin with? One method is to see if any folk remedies have any real effect and if so, figure out why and profit off it if it works. If your stuff works on some people, fine, good for them.

There is the possibility that research is often denied on those plants if they can produce a high that gets black market value, but lots of controlled substances are still used for medicine, so it’s a bit of a wobbly possibility.

I’m not saying it doesn’t work AT ALL, mind you. Just not often enough to look profitable.

Report comment

I recently increased the amount of antidepressant I take daily – after checking in with my prescribing physician. I’ve been on meds for almost 22 years – I started taking them a few months after I got clean and sober. For me, antidepressants work; recreational drugs don’t. This is a fact of my experience and I ain’t lettin’ nobody undermine that – whether it’s other people in recovery who say I’m “not really clean” because I take SSRI’s, marijuana advocates who say pot will solve my problems, or people who have gotten well without meds – using ginseng or kava kava or whatever – and now oppose them. If it helps you have the life you think is best for you, go for it.

Whether I know what’s best for me or not is debatable, but I’ma do what seems to me to be best for me.

Report comment

You know how you feel better than anyone else.

A lot of us here–including the anti-psych crowd–are not against the use of SSRI’s or whatever. It’s coercive psychiatry we oppose. Involuntary. Obviously not your situation.

Glad you have a doctor willing to work with you. 🙂

Report comment

Thanks. I’m new here. Also recently left a job that had me on the ropes for too long – a lot of othering, gaslighting, random verbal attacks. Still a little defensive.

Report comment

Now see, I’m sure you are old enough to know what is best for you.

I also don’t like othering, I mostly resent the public and shrinks being in bed together, along with every institution as far as “othering” goes.

I am very defensive right now, because I spent my day strolling through stores in a small town where I raise the subject of their huge amount of people who look like they are not doing great and they tell me it was not a problem before they shut down the BIG mental center.

And in my newness to this town, I tell the rich storeowner about the very likely result of othering and how they will never get rid of their “problem” as long as they allow psych to deal with them and I try to enlighten them between the difference of psych and ancestral/societal issues.

And I walk away knowing that it is church.

The whole bloody town is one big church. With a belief system that applies to “others”

Report comment