You know those movies that start close to the end, zeroing in on some catastrophic scene, and then backing up their timeline for the big reveal on how they got there? Let’s take this otherwise fairly straight forward ASIST review and try that out:

<SCENE> It’s Friday, January 25, 2019, two days after I’ve completed the ASIST Suicide Prevention training at Northern Rivers in Albany, New York. I’m back in western Massachusetts, sitting in my car outside the gym preparing to log some steps on the treadmill. Before proceeding, though, I am mulling over the call I got a mere hour or so earlier from the Department for Children and Families (DCF) Child Protective Services (CPS) telling me that someone had filed a 51(a) complaint against me for suspected child abuse of my daughter. While I’m still in active mull, my phone rings again. I pick it up thinking it must be DCF calling me back to let me know whether the  report has been screened in or out for full investigation. But it’s not DCF. It’s the local police department, and they’re saying that Northern Rivers has asked them to do a “wellness check” on me. They want to know where I am. </SCENE>

report has been screened in or out for full investigation. But it’s not DCF. It’s the local police department, and they’re saying that Northern Rivers has asked them to do a “wellness check” on me. They want to know where I am. </SCENE>

True story. Now let’s back up to the beginning.

What on Earth is ASIST, and Am I Misspelling It?

ASIST is an acronym, extra ‘S’ intentionally left off. It stands for Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training Program. To the best of my understanding, it is seen as the intermediary step between ‘SafeTalk’ (a half-day training meant for anyone 15 and older who wishes to raise their “alertness” to signs of impending suicide) and ‘Suicide to Hope’ (a full-day “postvention” training meant for clinicians who are working with people who’ve struggled with suicide, but are currently “safe”), all as developed by LivingWorks. LivingWorks claims the mantel of “world leader in suicide intervention training,” and lists among their main aims, the creation of “Suicide-Safer Communities.”.

(You might have already gathered this, but in case not, “safe” is pretty much their favorite word ever.)

Now, as someone who has been deeply involved in making space for the topic of suicide and supporting others to do the same, I’ve been curious about ASIST for quite some time. However, I found a burst of energy to track down a training when I learned that my colleague, Caroline Mazel-Carlton, and I were slated to present on a panel with ASIST trainers come February. (If you want to learn more about the event to which I am referring, check out the Institute for the Development of Human Arts. They seem to be doing some pretty good work.) Wanting to be as prepared as possible, I located a training in nearby Albany, New York, and signed up for research purposes.

I went in not entirely knowing what to expect, but I was somewhat heartened by a review of ASIST that I’d read online. Aside from the cover image (suggesting that perhaps this approach was primarily for middle-aged white ladies), there was some decent stuff in there. Perhaps what most stood out to me was this:

“While most gatekeeper training models are linear – teaching a three-step process of identification, intervention, and referral – ASIST more closely follows [a] philosophy by teaching a Suicide Intervention Model (SIM) that does not necessarily result in direct referrals to professional mental health services.”

Hallelujah! Was this going to be the first mainstream training I would ever attend that wasn’t pretty much all about getting people into the mental health system? Were they going to make space to talk about the dangers of medicalizing human distress? Were they going to challenge the assumption that suicide is necessarily even connected to “mental health issues”? Were they going to understand that the psychiatric system has the potential to do more harm than good so much of the time?

I’d like to report that this training was genuinely, fundamentally different than its most notable counterparts like QPR (Question, Persuade, Refer). But… well, how do you think that turned out?

Hint: “Always encourage appointment with a medical doctor, now or later.” Page 13, ASIST workbook.

ASIST Started on a Cold and Cloudy Morn

It was a cold and cloudy morning. Soft music intermingled with fluorescent lights to create a… disconcerting ambience. No, really. You know that brand of music that plays in a massage therapist’s office? That was precisely what greeted me as I entered the training room where I was to learn all about ASIST. Added to the mix were slides rolling on a loop and offering factoids mostly ranging from nonsensical to vaguely interesting. For example:

- “Suicide rate is a measure of suicide for a group” (Courtesy Captain Obvious, best friends with No Shit Sherlock.)

- “Suicide is NOT more common during the full moon” (Alrighty then.)

- “Left-handed people are at slightly greater risk” (Huh.)

- “People in institutions are at higher risk of suicide” (Go figure.)

- “Many people who might have been famous have died by suicide” (Might have been? Wha..?)

Only a select few slides seemed substantive in their messaging. (“Suicide rates tend to be higher in aboriginal communities” is one example, though also a candidate for understatement of the year given that indigenous communities in the US, Canada, and  Australia have the highest rates of suicide, period.) One slide went so far as to suggest that there are some people who actually aren’t at risk of suicide — some precious, protected group. But when a training participant asked the trainers to identify which group that was, they just said, “Well, we wouldn’t agree with that slide.”

Australia have the highest rates of suicide, period.) One slide went so far as to suggest that there are some people who actually aren’t at risk of suicide — some precious, protected group. But when a training participant asked the trainers to identify which group that was, they just said, “Well, we wouldn’t agree with that slide.”

I guess that’s okay, because the very next slide said, “The facts of suicide are not easy to explain.” Apparently so. At least as ASIST would have it go…

ASIST Wants to Know When You Go Potty

Our first task as training participants was to fill out a survey at the front of the room. We were encouraged to walk up to a poster board, and put a check next to our role (family, clinician, etc.), whether or not we’ve known people who’ve struggled with or completed suicide and so on. There was also one other very secret question we had to answer on a slip of paper, then folded over and dropped in a bowl. That very secret question, of course, was whether or not we ourselves had ever been suicidal, and if so, how recently.

Once we were all answered up, one of the trainers furiously compiled the data in the back of the room, while another stood up front telling us that we needed to let them know when we were going to the bathroom. Yes, in a flashback to grade school, we were instructed to give them a thumbs-up sign when we were headed to the potty (or, in fairness, any other time we were leaving the room for “safe” reasons), or else — they warned — one of them would follow us to make sure we were okay. Because, they claimed, it was their job to keep us “safe.” I should have counted how many times the word “safe” was uttered in those two days, but “safe” to say it was too damn much.

(As a side note, I will add that I basically “held it” for most of this training because while part of my brain felt energized by the idea of running wildly in and out of the room non-stop just in order to keep them on their toes, the other part of me refused to participate in their thumb game while also really not wanting to be followed, and so I just tried to stay put. Until day 2. That morning, I threw caution to the wind and walked out with all my digits retracted. No one followed me, and I’ve been contemplating ever since whether it’s better or worse to follow through once such paternalistic expectations have been set.)

Then it was time for us to learn the results of our little pre-class questionnaire (for no discernible reason other than the fun they had collecting the data and reporting it back). Turns out 7 people had (lied and) said they’d never considered suicide in their whole darn life. But, should any of us more currently be struggling, the trainers wanted us to know that they themselves were among the eager helpers we could tell. Yeah. Right.

(I’m just going to drop a gentle reminder right here that this story ends with this organization calling DCF and the cops on me.)

ASIST and the River of Suicide

Now, I’ve got to give ASIST props for at least recognizing that it is a model of intervention, and not prevention. Early on, trainers pulled out the ‘river of suicide’, and explained that prevention is actually what happens before someone thinks seriously of suicide (up on the other side of that dam at the top of the picture). Intervention is what you do when they’ve already descended into those blue suicidal waters, headed toward that big drop down below. And no, the “river” analogy never fully ended up making sense, even after their explanation. But, okay. Got it.

Next?

Trainers went on to mention several times how ASIST has undergone three major makeovers, but it’s a little hard to get a handle on whether it’s moved in a more or less medicalized direction. Notable changes have included shifting away from calling it a ‘Suicide Intervention Model’ (SIM) to a ‘Pathway for Assisting Life’ (PAL). Of course, that just sounds like a lot of euphemistic shuffling to me. Reportedly, the model makers also claim to now have moved “beyond risk to promoting safety,” although assessment-oriented questions (like “do you have a plan”) still reign central. Meanwhile, I’m unconvinced that a single one of these ASIST folks could adequately differentiate between assessing risk and promoting safety in actual practice.

But, let’s back up and take a look at the overall framework… I was admittedly (momentarily) excited when I saw that phase one of the three phase line-up was “Connecting.” That is, until I saw that it didn’t just say “Connecting.” It said “Connecting with suicide.” That’s right, phase one isn’t about connecting with another human being. It’s more about sussing out whether or not that person is contemplating their own death. And all that sussing about like an overeager truffle hog is initiated by what ASIST deems an “invitation.”

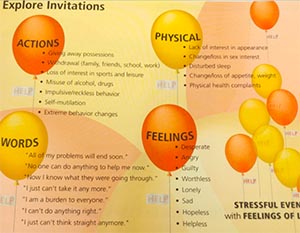

Yes, in a fit of balloon-fury and graphically questionable decision making, ASIST folks want us to know that “invitations” can come in any form. Basically, those “invitations” are anything another person might do or say that gets us thinking something might be wrong. But make no mistake: In spite of the voluntary-sounding nature of the word “invitation,” it really doesn’t matter if they meant to invite you or not. And, much like if you were a vampire, once you’ve been “invited” in, there’s not really any getting you back out according to the “ASIST way” until you decide to leave yourself.

Meanwhile, phase two is about understanding choices, which basically translates to listening and asking questions to learn what’s actually going on for someone. Thank goodness for that much, but don’t get too comfy there. Because you’re basically just waiting for the “turning point” where they signal readiness to consider the next step on your ASIST checklist.

Phase three is said “readiness” phase. It’s called “Assisting Life” and basically boils down to “disabling” one’s suicide plan (i.e., confiscating the “means” with which they were potentially going to kill themselves whether they like that idea or not), and building a “safe plan” in its place. Yes, the dreaded “safe plan.” (I will give the trainers some credit for at least differentiating between a safe plan and a safety contract, noting that the contract and related signatures are problematic and usually about the clinician’s safety more than anyone else’s.) Though, don’t worry. If someone is “unable to participate in the intervention,” you’re always free to “activate emergency response” and “24-hour monitoring.” (Page 10, ASIST handbook)

ASIST Makes You Safe… For Now

There really isn’t much more to ASIST than a lot of emphasis on paying attention to the verbal and non-verbal cues someone else is sending out, asking them honest questions in hopes of honest answers, and supporting them to think about how to move forward. Trainers even spent a fair amount of time emphasizing the importance of partnership over control, or necessarily following all the steps as they’re written on paper.

However, unfortunately, that stripped-down version of what ASIST is all about doesn’t address how it gets at those points, what harmful beliefs or practices people tend to cling to and incorporate in the absence of support to unlearn them, or what it misses altogether. For example, ASIST fails to address:

- How quickly “invitations” can turn into raids

- How little curiosity and listening to someone’s story might mean if you’re simply trying to fit what you hear into a particular box

- How the language and rigidity of a “safety plan” might be off-putting and problematic for many

ASIST also glosses over how utterly useless any brand of suicide risk assessment has turned out to be according to just about any and every formal assessment, the potentially harmful impacts of hospitalization (aka “24-hour monitoring”) especially when involuntary, and how unlikely someone is to tell you the truth of their struggles if they realize you pose any kind of risk to them being forced into the hospital as a result. It also misses the mark regarding how an agenda that focuses on whether or not someone is willing to say “I am suicidal” can get in the way of supporting them to talk about what they’re actually struggling with underneath all that

Additionally, trainers spent a substantial amount of time explaining that ASIST is only about making someone “safe for now,” because “safe” in general might take much longer and involve a “warm hand off” (gag) to a clinician who can see them ongoing. “Activating” other more forceful responses behind a person’s back while someone else “keeps them talking” was also promoted multiple times by both trainers and participants.

- Safe/safety.

- Invitation.

- Partnership.

- Connecting.

- Turning point.

- Warm hand off.

- Activating.

I’m building a list of words and phrases that ASIST trainers and I might need to get together to unpack real soon.

ASIST Brings Out the Stereotype in You

ASIST in itself is kind of a stereotype. What do you do with someone who might be suicidal? Well, you ask them if they have a plan! Come on. What else would you do, silly? Then you substitute the suicide plan with a safety plan, and if all else fails, call 911. Then (at least for some folks) you get to stop caring because you did what you could to “CYA (Cover Your ASS),” and now they’re out of your sight, so what happens next isn’t on you at all. Done!

ASIST’s approach is nothing new, and has probably only developed the reach that it has because people are so terrified to talk about death and dying in any form that they crave something that at least creates the illusion of morphing complexity into the concrete. Yet, this sort of model isn’t just a stereotype unto itself. It can also serve to draw out the stereotypes lodged in you. Especially if you happen to be a young clinical type.

By late morning on day 1, we found our larger group split in half. And, once divided, we dove right in to talking about our beliefs about the topic at hand. While likely the best part of the training in most regards (given it had nothing to do with the actual ASIST approach, and was simply about exploring common societal beliefs), this is where certain clinical archetypes began to show up.

Young and idealistic newbie therapist: At some point during the dialogue, I asserted that the system is designed around the “safety” of the clinician, not the people seeking support. I further explained that that was a large part of what drives so many people to feel they can’t be honest with providers for fear of negative consequences like forced hospitalization. This, of course, is where young and idealistic newbie therapist stepped in (“I just want to challenge that a little bit”), and told me how it’s not really that way anymore, and their training really encourages them to keep people out of the hospital nowadays. Thanks, newbie therapist guy. In all my years of being in the system and supporting and working side-by-side with other people who have been or are receiving services in the system, I never would have known that if you hadn’t said so. Clearly your two minutes of professional therapy work amount to more wisdom than my lifetime.

(I’d like to once again take this opportunity to remind everyone that this story ends with DCF and the cops.)

Young and proud soon-to-be college grad: When discussing who was to be held “responsible” if someone does attempt suicide, young and proud soon-to-be college grad jumped in to throw around theories about underdeveloped or impaired frontal cortexes, serotonin, dopamine, and more. She threw around so much schoolbook knowledge that she sounded as if she were taking an oral exam. She was confident. She was excited to soon be entering the clinical world all grown up and graduated. She was so super sure of what she was saying. And, it might have been more endearing, had so much of it not been so damn wrong, and such a big indicator of how little anything has changed at all.

Young and cocky CYA guy: Young and cocky CYA guy was late. Apparently, his pipes had frozen overnight, and there was some issue with his daughter and her car seat that he had to tend to before gracing us with his presence. But all that lateness didn’t come with an ounce of humility. Yes, this is the guy that openly told us that he’s all about the “Cover Your Ass” approach, and that his “therapy style is dismissive sometimes.” (Never before had I known that jackass was a therapy style. Go figure.)

I wish I could remember these three young people’s names. There was Griff (short for Griffin), Steve, and… Ashley, maybe? I wish I could find them and make them read this, and make them hear about what happened to me.

What happened to me after I was assured by an ASIST trainer that partnership was so important.

What happened to me after I was assured by young and idealistic newbie therapist that they’re now trained to keep people out of systems.

What happened to me because of all their dismissive assumptions, and actions taken out of smug CYA motivation, or even retaliation, and without any regard to the impact of their abuses of power.

ASIST, DCF, and the Cops… Oh My!

By the morning of day 2, we were supposed to move into role playing. Each of us were paired off with the expectation that we would perform two role plays: One as the helper and one as the helped. We would act out each scene in front of our small group and trainer, and receive feedback on how we were doing with employing the ASIST model. We were warned ahead of time by a trainer to “not use a scenario that would hit too close to home.”

I probably should have listened to that warning and used a fake scenario. Oh, yes, I should have listened. But, I had to make a choice. Either I was going to pull out of participation altogether and leave my partner stranded for how much I didn’t believe in the ASIST model, or I was going to make best use of this small platform I was being given. I decided on the latter.

By the afternoon of day 2, I was role playing myself back when my daughter was around one year of age. I played a mother (myself) who was having visions telling her to hurt her baby, and how she was struggling with wanting to die just to make all the visions and nightmares stop. That experience was real. I wrote about it in Miscarried Life back in 2013. I’ve shared about it all over the US, and in parts of Canada and Australia. After the role play was over, I explained to the ASIST group gathered before me that it was a real life experience, and how I’d moved through it; what had helped. I also said explicitly that I’d never actually felt at risk of hurting my daughter. I told them, “Just like you might have an annoying neighbor who tells you to do something that you never feel you actually have to do, I never felt like I needed to listen to those visions.”

Now, I’d shared that story because of all the concerning things trainers and trainees had said in reference to “clients” (“Clients are hardly the bedrock of mental health. There’s no telling what they’ll say or do”), or those deemed “psychotic” (“People with psychoses won’t be able to engage in these sorts of conversations”). I also shared it because it challenged all the conventional ideas people have about what is helpful at all. Normally, when I share, at least one mother approaches me and thanks me for speaking about it, for helping them feel less scared and alone. But, in this instance, it led someone in that group to call the Department of Children and Families (DCF) on me.

Yes, whoever that was (and I’m pretty sure it was the trainer because DCF had been given my unlisted work cell phone number and the address I used to register for the training) deviated from the lip service ASIST gave to the idea of asking questions and getting to know the “story,” and went straight for the “better safe than sorry” that is the true underlying theme of this model. Except, I would argue that “safe” shouldn’t include systems demonstrated to discriminate against parents with psychiatric histories coming into my home. And “safe” shouldn’t include reporting behind my back something I was openly discussing with the group, and about which I encouraged people to ask me questions.

So, after that call, I did what most people would do in today’s day and age: I took to social media and posted what had just happened. I also e-mailed the organization. In both spots, I included the following statement:

“This is why people kill themselves rather than be honest with anyone in a clinical role, ever. Whoever did this has done *such* a disservice. If they felt confused by my story, they could have asked me questions or asked that I clarify. What is the point of a training like this if one can’t even do that much?”

And it is this statement that I believe the Northern Rivers folks used to justify what they did next, which was to call the police. In a move that I believe was pure retaliation for posting about them on social media, Northern Rivers had the cops come to my workplace and search around for me for the purpose of a “wellness check,” because (as they told some of my co-workers) of a “concerning Facebook post.” Fortunately, the police were satisfied with talking to me on the phone, and went away after that.

ASIST is More Powerful Than Me

Only about a month before the ASIST training, I facilitated an Alternatives to Suicide training in that very same city. In that training, we went through a segment where we broke down all the unhelpful elements and assumptions of standard approaches to suicide, and how many people are driven to keep doing unhelpful things largely out of a fear of liability. One training participant, however, asked a very good question: If there’s research saying conclusively that practices like assessment aren’t helpful (and there is), then why aren’t people more afraid to be held liable for using such a discredited tool rather than not using it?

The answer lies in power and dominance. Approaches like ASIST follow the standard practices, and standard practices needn’t be good practices. In order to limit liability, they must simply be the most accepted (which also often aligns with whatever is perceived to be most profitable to some particular group or corporation in this capitalistic society of ours). That is, in fact, precisely from whence they draw all their power. And those with that power are the ones who get to decide what “safe” and “risk” even mean.

Ever since the cops and DCF were called on me, I’ve been trying to see it all as a gift. What better proof to counter Griff (and all other providers who claim it’s “safe” to tell) than what happened to me? What better evidence that our system responses are seriously off track?

I have a fair amount of privilege. I’m white, and have the confidence that comes from being fairly educated about my rights, the system and how it all works. I work full-time, and am reasonably well regarded in various professional circles. I wasn’t at all in actual distress. (Well, except for the distress that came from sitting through the training itself.) Fortunately, the police didn’t bother me beyond that phone call, and DCF screened me out of a full investigation. The worst consequences I experienced were embarrassment at work, and needing to sit my kids down to tell them what’s going on, and that people might approach them at school with questions. (My daughter was scared, near tears, and expressed fear because — at age seven — all she really knows of the police is that when they are involved it’s usually because someone is going to jail.) But, if things could get this far with me, what would the likely outcome have been for someone else with less privilege and more fear? How often are families disrupted and torn apart with little to no reason at all? We needn’t look far to see what’s going on around us all the time.

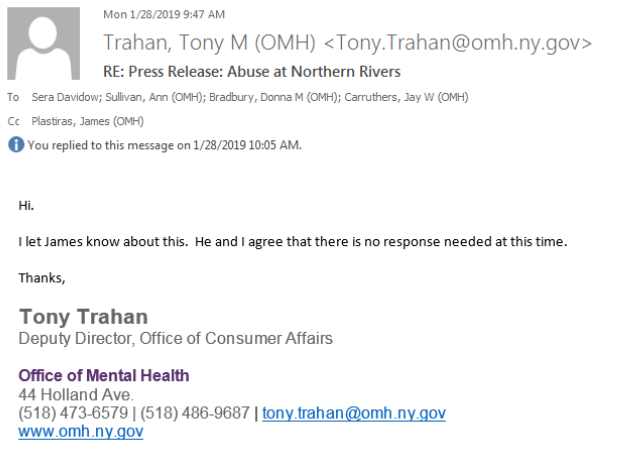

So, I’ve taken this gift and turned it into a press release. I’ve now sent that press release to all sorts of media contacts, the Northern Rivers CEO and COO, all the ASIST trainers who facilitated my class, and several Northern Rivers Board members. Additionally, I sent it to the Commissioner (Ann Sullivan) of the New York Office of Mental Health (OMH), the OMH Director of Child and Family Services (Donna Bradbury), and the one remaining employee of the OMH Office of Consumer Affairs, Tony Trahan (who was left on his own after the Director of that Office, John Allen, was charged with 29 counts of child endangerment and fired from his post). Not surprisingly, they’ve all been silent in response. Well, except for Tony Trahan who accidentally (I assume) copied me into an e-mail that he wrote just to say he’d be ignoring me. I replied immediately asking if he couldn’t even spare a “I’m sorry that happened,” but got nothing back. I guess I just have to see this as the part of the “gift” where I’m also given hard evidence about how useless and incompetent these systems are in handling the complaints about the terrible things they do.

In the End, ASIST is Not Safe

Perhaps one of the strangest things about the ASIST training was its incessant focus on “safety” as it intersected with all the trainers’ insistence that we might not be safe. We weren’t safe to say openly whether or not we’d personally struggled with suicidal thoughts. We weren’t safe to go out of the room on our own without assuring the trainers we were okay. We weren’t safe to use scenarios too close to our real life, because we might not be able to handle the feelings it could bring up. (At some point, one has to begin to wonder if what the trainers meant is that they wouldn’t feel safe…)

How strange that ASIST insists it’s so important to be able to talk about suicide openly, while simultaneously signaling that it might not be safe to do so. And, in the end they were right. It wasn’t safe. Not for me. Not for anyone who wasn’t a clinician. Not for anyone who might actually need or want some sort of “help.”

Yes, ASIST is more powerful than me. It gains its strength from a system that is more powerful than all of us. And, it apparently sits in a place that grants its wielders immunity when they use all their strength to siphon power at someone else’s expense. In the end, everything that happened to me was the result of fitful efforts on the part of providers to make themselves feel “safe,” all wrapped up in the smug warmth of widely misunderstood concepts like “mandated reporter.” Ultimately, ASIST is just another cog in that same old system.

But, then, what do we do with the fact that the sort of loss of power and alienation experienced by so many people who are “helped” is exactly what drives so many of us to want to kill ourselves? Is the goal to actually support people to build lives that lead them to want to live? Or do we have to finally acknowledge that we’ve been tricked, and that so much of what exists is set up to keep people as comfortable and blame-free as possible when those people go ahead and die…

* * *

NOTE: If you know of a media person who might be interested in this story, please e-mail me!! And in the absence of that, I hope you will share this article far and wide.

For more information on the topic of suicide along with ways to actually support people who are contemplating death:

- Training: Alternatives to Suicide

- Article: The Best Way to Save People From Suicide by Jason Cherkis

- Article: Life & Death: Robin Williams, Suicide “Prevention”, and the World as We Know It

- Article: Suicidal Tendencies, Part I: I’m Suicidal Because I’m Mentally Ill Because I’m Suicidal

- Article: Suicidal Tendencies, Part II: The Real ‘Stigma’ of Suicide

- Article: Suicidal Tendencies, Part III: So, When Do I Get to Call the Cops? by Sera Davidow

Sera, thank you so much for sharing this. I’ve been wondering about you ever since I saw you mention the “wellness check” in your last blog.

We don’t always see eye to eye but you are absolutely my hero today. Yes you are privileged but it still takes a boatload of bravery to fight back against systemic abuse, especially so publicly. You’ve done a public service by documenting this so clearly and completely. You’ve given voice to those who have been harmed by punitive suicide prevention strategies.

Well done.

Report comment

Thanks, kindredspirit. I’m doing everything I can to get this story out there. No surprise, of course, that the media isn’t interested. First, I’d have to convince them that I shouldn’t, in fact, be locked up forever in order to get them to care. But, I’m working on it as best I can. 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

I’m sure you don’t want to hear an extended presentation on strategy and tactics. So I will let it suffice to say, once again, that hoping against hope for the corporate media to cooperate in putting out information detrimental to a corporate agenda is like bashing your head into a wall, as your experiences with the Globe confirm. Revolutionary change comes from the grassroots, not from the top, and such efforts will not be reported in the media until they start to become successful, at which point the corporate media will step in to sensationalize and distort the issue, and do their best to make you seem crazy. People from any political perspective who want to defeat psychiatry need to develop their own means of communicating and reaching out to the masses of “survivors.” (And that DOESN’T mean Facebook!)

Btw has this organization “officially” responded to any of your publicity yet? Having a kick-ass, take-no-prisoners response, for those who are paying attention, would be a priority, I think.

Report comment

Oldhead,

Yes, I know you’re largely right, and I can’t help but try. And no, not a word… although I e-mailed them *ALL* (Office of Mental Health and Northern Rivers leadership and Board members) again yesterday with a link to this article, and telling them that I am *formally* asking for information on how to file a complaint which I believe they should be legally compelled to provide to me… But nope, nothing.

-Sera

Report comment

I love complaints procedures, especially when making the fact I put a complaint in public on social media and such like.

Better still, make the complaint at their next training event, with a banner drop n all.

Report comment

I’m late to this party, but I want to add a thought about making a public complaint at a training.

The people who put on trainings don’t work for Livingworks, they work for local, usually non-profit, organizations. Doing some sort of protest at a training would be ineffective, since it doesn’t reach the intended audience.

However, the American Association of Suicidology (AAS) has an annual conference and a scholarly journal, and is well-attended by leaders in the field. They also invite people with lived experience to attend the conference, and the number of those people increases every year. Getting involved there would enable you to connect with like-minded individuals and get a seat at the table with decision-makers in multiple areas – crisis hotlines, the education system, government and research.

Report comment

wow

Report comment

I agree with kindredspirit: Pushing back against the trainers and the mental health ‘authorities’ and ‘experts’ is hard enough but to do so publicly in a way that could put you at risk of being defamed, blacklisted, or fired by your colleagues is very commendable. By going public, the rest of us don’t feel so all alone in our individual battles. Each of us must come out of the closet a little bit more and exhibit just a little bit more courage to do what we know is right. Speaking truth to power is like a muscle that gets atrophied for individuals and family members who get ensnared in the mental health system but the more people exercise that muscle the more people can protect themselves and their loved ones from harm. The more they can protect themselves, the more people they can shield with their example, Eventually, a small army of well conditioned people will be able to shield themselves and others.

Report comment

Thanks, madmom. I like that idea of an army. 🙂 Unfortunately, if anything, I think so many people have headed in the opposite direction of any real fight, but hopefully we can turn that back around. 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Thank for the Article, Sera. I agree with madmom.

Report comment

I think this helps demonstrate that “survivors” constitute a quasi-class transversing standard class barriers. Also confirms that psychiatry — and the psychiatric mentality — constitute a parallel police force. Anyway, glad you eluded them this time.

Report comment

Thanks, oldhead. I’m glad I eluded them, as well… Although, I did get something back from a media person suggesting that they would have been more likely to be interested in helping to get my story “out there” if the consequences had been worse. Oy.

-Sera

Report comment

Ah, if only you could have engineered a REAL disaster – simple extreme suffering just doesn’t get the audiences it used to…

Report comment

Yes, exactly. Unfortunately.

Report comment

Sera, what a nightmare the ludicrous training course turned out to be. Once again it shows how insincere and calculated mental health care can be. Thank you for sharing and I agree with KindredSpirit you have done an amazing “public service” and “given voice to those who have been harmed”. Also as Madmom says we all need to start speaking out and getting our stories out there. I had no clue how dangerous it was to set foot in a psychiatrist’s office and unfortunately many, many people still don’t. It is a shame that it is so difficult to get the media to report these stories. Any chance of going on a talk show maybe?

Report comment

Rosalee,

I’d love to go no a talk show and talk about this. I think the challenge is getting a talk show to want me. :p If anyone has any ideas, I’m more than open to them! Thank you 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

I experienced a number of suicidal hospitalizations and extrapyramidal disability in the early 1980s at Galway Southern Ireland. The Hospitalisations and the Disability stopped when I stopped the “medication”:-

https://journals.lww.com/psychopharmacology/Abstract/1983/08000/Suicide_Associated_with_Akathisia_and_Depot.6.aspx

Report comment

Thanks for sharing, Fiachra. You’re so not alone in that, but it’s still not nearly well enough known that that can be a thing.

-Sera

Report comment

Thanks Sera,

A lot of people on these “medications” are forced to take them, and the treatment can in a sense be a “death sentence”.

Report comment

I do agree, the “mental health professionals” are obsessed with suicide. My first experience with a “mental health professional” included the “Have you ever thought about suicide” question. I was there because I had antidepressant (“safe smoking cessation med”) withdrawal induced brain zaps, and wanted to know why I had the brain zaps.

I had to think about the suicide question, then said maybe once, 20 years prior, in high school? This turned into “suicidal thoughts – no plans.” Maybe, 20 years ago? What a crock of sh-t our “mental health professionals” are. And, of course, I learned what the brain zaps were from the internet, since none of the “mental health professionals” knew what brain zaps were for three more years.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247806326_'Brain_shivers'_From_chat_room_to_clinic

I must agree, it’s apparently not “safe” to confess to ever having a suicidal thought to any “mental health professional” ever.

Report comment

Yes, that’s exactly what I experienced, the psychiatrist was the one who was “obsessed” with suicide. I was tricked to see her for “help with sleep meds” and as I sat there bald, emaciated and fatigued from cancer treatments she suddenly asks me if I am “suicidal”. Me, puzzled: “What? No of course not” Her with a skeptical look: “Are you sure?” Me in an effort to convince her: “Yes I’m sure, I don’t have a Will and would NEVER want to die without a Will”.

So she documents: “Suicidal++, only thing stopping her is she doesn’t have a Will”.

Why would I even bother doing chemo if was going to kill myself?

It would be hilarious if it wasn’t so dishonest and calculated of her to twist words, manipulate and write lies.

Report comment

OMG, that is awful! “Are you sure?” Maybe you should have said, “You sound so disappointed. Would you feel better if I were suicidal?” Nah, probably would have gotten you locked up for “excessive snideness disorder.”

Report comment

Yes Steve, wish I was more quick witted and assertive at that time as would’ve loved to say something like that! As you say though, every thing you say will be held against you and even if you are polite and positive, etc, they just twist your words into something negative and entirely different in order to have something to hold against you.

Report comment

It’s always easy to think of what to say after the fact. I seldom come up with these zingers when I’m actually talking to the person who is messing with me. Maybe I need to learn to stop and say nothing for a while instead of immediately responding, and I can come up with some better routines on the spot!

Report comment

Sera you are far more likely to get your story into the media than most of us are.

If you are going to use your own story as illustration, as you did in the workshop, I’d suggest putting it in third person: “This happened to someone I know.” Don’t say it was you. Just for future reference.

In a recent job interview I was asked if I ever had a conflict with a coworker. I haven’t. I did have a conflict with a supervisor. She had deliberately picked on me and did what might qualify as workplace bullying. Instead of saying that happened to me, which would have made me look bad in the job interview, I stated that I witnessed her doing unethical things including belittling another worker. Here, of course, I put it in third person.

All of life IS like a job interview. People constantly criticize and constantly seek out ways that we are faulty, abnormal, or diseased. We are all actors. We play roles, some of us many roles. Acting is lying, whether we realize it or are simply fooling ourselves.

Report comment

Julie,

I hear you, and you’re not the person to suggest I make it about someone else. However, it loses a lot of power when I can’t say “that was me”. Being able to say “that was me” is a huge chunk of the power of sharing these sorts of stories at all. It’s where we get to challenge people’s assumptions in how they might conjure up an image of the person about whom that story is true… I know it’s a risk to me. But in spite of all this, it’s a risk I continue to be willing to take … most of the time. 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

Hi Sera,

thank you for sharing your experience, especially how you were reported to the authorities. As much as I’ve kept my wife out of the system, your story is a cautionary tale to me because this journey she and I are on is so hard many days that my personal journal is filled with the sigh that I’m so tired of life and the wish that I’d never been born. To me that feeling is always there, ebbing and flowing, but it’s kind of freeing, knowing that if things ever get too bad, I have an out, and with that ‘out’ it gives me power over those feelings…

…And yet on my blog I wrote about how to help someone feeling suicidal from my personal experience, and fortunately none of my immediate family who read it called anyone on me. And when my wife and I take our daily walks together, we walk past a counseling service and part of me loves the idea of just getting some help and support on the days when it’s so hard helping her on my own…but your experience shows to me that my wife’s insistence on our anonymity is probably for the best, even though it means we can’t help others, because it protects me as well as her, sigh…

I’m glad nothing worse than a phone call and a little embarrassment happened to you. Thank you for being willing to share for those of us who can’t yet…

Sam

Report comment

Thanks for sharing that, Sam. The idea that knowing that suicide is an option brings a sense of hope, control, and willingness to *keep living* is so hard for so many people to grasp, and yet so true for so many of us.

-Sera

Report comment

Sera, a surprisingly large number of people commit suicide when locked up for it. I don’t have the information right now. I believe it can be found in the index of An Unquiet Mind by Kay Redfield Jamison.

If I had a suicidal friend I would keep an eye on her, call her, show her unconditional love and try to keep her spirits up. But you don’t find much love or hope in a psych ward. 🙁

Report comment

Hi Rachel,

Yes, during and following hospitalization is when suicide “risk” is actually the highest according to research, and hospitalization seems to have long-term impact on suicide rates even for people who were hospitalized for reasons other than wanting to kill themselves. It’s pretty staggering and largely ignored data.

-Sera

Report comment

Sera,

This I believe is because of the “medication” (starting, stopping, changing).

(A “schizophrenic” is also most likely to kill themselves in the early years after “diagnosis” and here again I believe this to be because of “medication” (- it takes a number of years for a person to familiarise themselves to psychiatric drugs)).

There are also alternatives within psychotherapy to the strongest psychiatric drugs available.

Report comment

Fiachra,

I think the drugs – and their largely unacknowledged contributions to *increasing* emotional ups and downs, disconnections, etc. – definitely have a role. However, I hesitate to say they’re all to blame. The hopelessness that comes with being given some of these diagnoses, the “prognosis” people are given, the hospital environments and how powerless people can feel… All of it also has a role.

Iatrogenic effects are bit… and with more than just the psych drugs.

-Sera

Report comment

Thanks Sera,

I’m definitely talking from my own experience and outlook.

On the subject of “prognosis” after nearly 4 years in the psychiatric system my “prognosis” was atrocious – and what followed was 35 years of Wellness.

(As regards Suicidal Tendency I’m referring to drug induced Akathisia – and for me I had no control whatsoever).

Report comment

I have to agree. The very fact of being told that your brain is broken and there is nothing you can do about it would make anyone feel hopeless. Add to that the frequent invalidation of one’s own experience and internal knowledge about what is going on, and you don’t need a drug to make someone give up. Not even getting into the horrors of “involuntary treatment.”

Report comment

Steve,

My experience was in the 1980s and my Consultant Psychiatrist (in Ireland) kept telling me that my problem was that I couldn’t hold down a job (- but I had to come off my “medication” to get to this position).

Report comment

The love and hope that I found was in some of the other “patients” who were locked up with me. The best “treatment” I ever received was at the hands of other “patients”.

Report comment

What they did to you is a crime https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swatting and time wasted on false reports is stolen from finding children in real danger.

I recently had a friend sending me some I am going to kill myself texts and I texted back WTF are you doing delete those texts right now. I was left with those scary thoughts of what if she does something stupid and it would be my fault for not doing something. She is over 1000 miles away only gets texts, minutes ran out but I did the math on it and calling her mother and saying I was getting these texts or the authorities I would just become more evidence to support the belief “you can’t trust anyone.” Then if there is another crisis of course I would not be contacted.

Its a tough spot but I know what would happen if if I took some action and the authorities showed up, a complete nightmare. Police cars and flashing lights in front of the house making the neighbors come outside to see you upset getting dragged off maybe an ambulance. That would be “helpful” for years to come being the one on the block dragged off by the authorities.

I would not have slept better cause she was “safe” after inflicting that nightmare but I am thinking people who don’t know what “help” is certainly would consider calling help.

This comment would have been different if I didn’t just go through this, probably would have just wrote about that hospital falsely labeling me suicidal as a billing and holding excuse and what a nightmare that was. All I can say is it really sucks when someone is saying suicidal things and you personally know what “help” really is.

Report comment

Yes, The_cat…I agree and what a horrible reality that is… “All I can say is it really sucks when someone is saying suicidal things and you personally know what “help” really is”.

What the masses don’t realize is if people are distressed and they get “help”, well then they are really going to have a much BIGGER reason to be distressed after getting any so-called “help”.

Report comment

And they quite likely will kill themselves anyhow. With psychiatry even if you “live” it’s not a good life!

Report comment

Hey The_cat,

Yeah, I’ve been in similar situations, too and had to make some really difficult situations. Ultimately, I so appreciate where you landed. It’s where I’ve landed, too. People *need* to be able to say some of those things to other humans and not get locked up for it. That said, there have been occasions when I’ve also said to people, “Hey, it was super unfair when you said that and then disappeared, and I’m feeling angry about that right now.” That (treating them as not so fragile that they can’t handle hearing how what they did impacted me) also turned out to be good for our relationship, though.

Thanks,

Sera

Report comment

I got a voice call yesterday she is alright. Texting sucks, you can’t hear how people are feeling.

Report comment

I’m glad Cat.

At least she has a friend like you. Too bad it’s long distance.

Report comment

It is definitely a lose-lose situation!

Report comment

And PS she lives with her mother and family, I had that much at least knowing she wasn’t alone someplace even if problems with them contributed to the distress in the first place. She just wants to be on her own and her comes that word the family wants her ‘safe’ with them and she doesn’t have the money to leave and come live around here again. Going crazy with boredom not accomplishing anything being stuck and she is struggling with mental stuff I don’t even know what describe it using DSM code but psychiatry won’t help. Her mother was asking me but there is really nothing they have to ‘fix’ whats going on. When she has money and a place she functions just doing her thing even if its strange sometimes.

Report comment

“DSM code.” I like that.

Psychiatry tries to categorize behaviors which are bad or self defeating or odd or simply ones they don’t happen to like into “diseases” like astrologers drawing lines between stars to come up with zodiac signs.

People are too complex to fit into the boxes shrinks try to stuff us into. The labels are worse than useless and do nothing to end the suffering. The only people these help are the shrinks in their endless quest for power and money making billing codes.

Report comment

Thanks Sera and kudos for writing about this! I am so glad the interactions were relatively minor- which says everything about my own life narrative.

There are several layers to this workshop and how it played out for you.

I admire your bravery and know exactly where you were coming from and my guess is one of the inner voices was saying don’t go there but you did and I probably might have done the same twenty years ago. Now no.

1) This is now and we are living in a mess of a hair trigger world. We all are walking on broken glass so to speak.

As I look for societal connections to make or observe systems of all kinds I see knots and tangles, holes, and rips in fabric.So I try to see all folks as coming from this life trauma framework but so very hard and always one step forward and two steps backward.

So my guess all the folks including trainers were co- existing with trauma and were somewhere in different levels with all of that. Your real ness probably scared them witless!

So the one of the two things I want to bring up is we all all know folks who have tried or did commit suicide regardless of wherever we are on the spectrum and I would stand my ground that it’s not if you Thought this life is not that great my options are very limited and any hope grows dim at one time or another.

No group has ever brought out the connection of how we as a society not only cannot desk with death but suicide is almost a verboten word almost to the level of a taboo.

Read the obits. Listen to the muddle story of a cousin’s sudden death. The whispered stories that children tell each other at sleepovers. You know that house in the corner? This were the whoever offed themselves by whatever method fill in the blank.

In my old parish there was a suicide cluster and lots of wtf type of deaths in the passing years. I think trauma of many sorts played a role.

My list of folks and peers who have chosen somehow to walk away is long.

And there are so many ways to do that.

Not one so called helping profession ever ever bothered to asl how have you been affected by suicide. Never because

way way to scary and oh my the therapist would have experience your loss – secondary or tertiary trauma.

12step programs have been the only place I have felt this is even acknowledged and I know other new groups. This is just the first that comes to mind. I am aware of others.

The second piece is it wasn’t always this way. I really knew a Vietnam Vet shrink who would be like folks are going to do what they are going to do. There were more folks out there after the 1950’s and then it fell apart fairly quickly especially in the eighties.

And yes there are dangerous situations and like you been there done that but not anything like your workshop.

I hope the media picks up on this. There are some signs but not enough and I am too old to be patient for a long haul perspective. Trauma centers now.

Report comment

Thanks, Catnight! The taboo you speak of … the reality that a lot of this comes from a fear of talking about death at all… is definitely one of the things we try to address and bring to the surface with our Alternatives to Suicide work. And it was so weird to watch the ASIST folks twist themselves around the idea that we should be able to talk about suicide, while still sending such a strong message that it should also be really hard and upsetting whenever we talk about death. And yes, it definitely doesn’t have to be like this. There are certainly cultures where talking about death in all its forms is so much more normalized. The issues – being able to talk about death at all and being able to talk about suicide – are absolutely intertwined.

-Sera

Report comment

Sera

This is a very important blog for many reasons. Not only does it further expose the entire “mental health” system, but it shows the major shortcomings and limitations in all these so-called “newest” and “highly innovative” and “cutting edge” reforms, that are nothing but regurgitated pablum that cannot escape the confines of a thoroughly corrupt system that can NEVER be reformed.

This blog also raised issues of strategy and tactics for working “inside the Belly of the Beast.

I loved all your “cutting edge” and appropriate use of sarcasm describing this personal and political nightmare.

I can identify in some ways with your plight of being a “lone voice” in a sea of ignorance and arrogance. I felt that way in my 22 years working in community mental health. I know the tense feelings of being in a trainings where you know exactly what is so wrong with the presentation and you have to decide (in the moment and on your own) how to challenge the presenter without coming off as some “crazy disrupter.”

The times I did little to speak up, led me to beat up on myself for weeks and months after the presentation. Some times your “damned if you do and damned if you don’t.” But I always believe it is better to speak out and “shake the cage,” and then see what develops afterwards. There will always be someone (or a few people) who learn something and/or show support for what you have done.

Working inside this system (knowing everything you know) is so difficult. I don’t think its futile that you have sought out ways to expose what happen to you, including going to the media. I think it is worth the effort because we just don’t know when a “single spark might ignite a prairie fire.” Just make sure you don’t get your expectations up to high. I think I was a little overly disappointed when my formal complaints to the Mass Dept. of Public Health and Dept. of Mental Health went absolutely nowhere.

My only advice for future trainings like this is to try to never go alone. If you go with a few other people it will increase confidence and mutual support in the heat of the struggle. It will also help you sum up strategy and tactics as things develop.

Sera, great work and great courage. My only question is: what is going to happen when this training attempts to take place in Western Mass.? Do they (Asist) have the balls to come to this territory after how they treated you?

Carry on! Richard

Report comment

Thanks so much, Richard. And you’re absolutely right.. I shouldn’t have gone alone (from any other than a financial standpoint). Even before some of the worst things happened, it was still painful to be the lone voice in a sea of providers who were all on the same page with the terrible things they were saying. And it made my credibility much lower in a lot of ways.

And good question… Massachusetts doesn’t seem to do much with ASIST right now, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it moved in that direction. We’ll certainly be watching for it 🙂

-Sera

Report comment

The two word phrase which, to my mind, absolutely defines the oppression and untrustworthiness of the “mental health/social services” industry: mandated reporter. These words make me cringe big time. That’s what creates the police state dynamic.

At the center where I did my MFT training, a couple of the interns were chomping at the bit to report someone. That is wayyyyy too much power over unsuspecting clients, and dangerous to society at large.

I’m sorry you and your family had to go through that, but of course you turned it into a teaching moment. Excellent work, Sera!

Report comment

Thanks, Alex. Yes, mandated reporter is a serious issue, *especially* since so many people claim that it has anything to do with the topic of suicide which it most assuredly does not. But in general as well… It is a real issue. And what I think many people don’t realize is that once DCF is called in, it’s kind of like getting a diagnosis… I was thinking about my house after DCF was called on me. My kids aren’t getting abused. They’ve got pretty well supported, good lives… but how would DCF interpret my house not being so clean a lot of the time, and all sorts of other things that are just fine when you don’t have DCF looking at you through a particular lens…. Oy.

-Sera

Report comment

Right, it has to do with reporting suspected abuse or abusive neglect of kids, elderly, disabled, etc. So when you say “it’s kind of like getting a diagnosis,” this is where I think of the word “stigma” (in the truest, non co-opted sense of the word). That black mark is akin to the scarlet letter. People draw all sorts of false conclusions based on conjecture. In other words, guilty until proven innocent. And going around trying to prove innocence is the epitome of oppression, social dysfunction, and energy draining. In a sane and rational (functional) world, this would not be.

I applaude your courage like others have. This is what happened when I made my film to share my criticism of the system and it definitely had both a positive and negative impact, although in the end, the “negative” was only an initial perception based on the anxiety it produced, as it all led to good things. Changed my life for the better to speak my truth like that, and it also got me professoinally blackballed. Seems like those two go together! I’ve certainly no complaints or regrets in the slightest, all these years later. Quite the contrary.

Report comment

Youtube activism is over.

I went to look for those videos posted on YouTube by people who secretly record DCF abuse in their homes and the search results for this are all mainstream corporate news videos. YouTube rigged all their search results to favor corporate news organizations rather than actual YouTubers.

Its not actual censorship they just bury the results under 100s or 1000s of corporate news Youtube channels. I keep posting on the Infowars comment section that someone needs to make an “anti censorship” browser extension that works similarly to an ad blocker to block out MSM media results. I hope someone takes my idea and makes it work. I first noticed what YouTube did after Hurricane Micheal. It was impossible to find real YouTuber videos of the hurricane behind the wall of corporate media YouTube channels in the search results.

I still think people should record DCF, they are known to lie all the time.

Its just sad internet censorship once the thing of conspiracy theories is quickly becoming a reality.

Report comment

What does DCF stand for Cat?

Report comment

“Department of Children and Families”. How is that for some Orwellian shit ?

I think what the government really needs one big department of stay the F out of our lives that would include ditching this ASIST suicide thing that only screws people up more.

Report comment

I’ll never forget my ASIST training. It was required by my employer, who also conveniently was the only provider of the training in the city. The training was conducted by the clinical director and his wife. I had just been hired as an Administrator of a residential program. One of the first things the trainers said was “Nobody ‘commits’ suicide, they ‘complete’ it. We’ve talked to a lot of survivors and this is how they feel about it.” My first thought was “F- You!” I’m a ‘survivor’ by any definition of the word. My mother committed suicide when I was 12 and my step mother did 9 months later. I spent my adolescent years in and out of psychiatric facilities for suicide attempts that included everything from overdoses to cutting myself. I never once heard of or thought of suicide in such a way. And I never will. I have a set of grand parents that won’t talk to me because I remind them of my dead mother and the pain is too much for them. I don’t know that my mother’s suicide will ever have been completed. Needless to say, the trainers were just as respectful and professional for the rest of the ASIST program. The facilitator later had the audacity to complain to my direct supervisor that I didn’t participate much, after being instantly stifled and all but shut down. They preached the notion that all suicide is bad and nobody truly wants it. That we must always try to stop suicide. They claimed to be person centered when harm reduction would teach otherwise. My mother hung herself with a dog leash after finding out my father had an affair. This wasn’t her first attempt either. Advocates of euthanasia say mental health is ‘treatable’ and so, should be excluded, but whatever treatment she had access to was never going to solve the problem. She didn’t want to be here. In my early 20’s, I thought this was a failing of the public mental health system and took it upon myself to become an agent of social change, but these days I can recognize there is more to it. I will no longer fear licensing issues or litigation. It is not moral or ethical of me to impose my own desires or beliefs on another, so I will not use motivational interviewing, only simple interviewing. If only someone had the strength to give my mom the okay to do it, maybe I could have been there. Maybe I could have said ‘goodbye’. Maybe, she wouldn’t have died alone in a cold garage in northern Idaho.

Report comment

Thanks, Bricew. It’s always interesting to me how important language is, and how we hear words differently. I do often challenge people re: “Committed suicide” when I’m in training environments. I do *not* ever tell people they “can’t” or “shouldn’t” use it, but just offer food for thought which is this: “Committed suicide” comes from a time when suicide was being painted overtly as illegal (as in “committed a crime”). Based on that, I personally try not to use that frame… but nor am I fond of “completed suicide” or ever telling people *what* precisely they need to say.

In my experience, telling others (and especially others who have first-hand experience with something) precisely what words they’re supposed to use comes from a special brand of ignorance and insensitivity.

Thanks for sharing some of your mother’s story as it intersects with your own. I too struggle with this idea that we should get to put our own priorities of people living as long as possible on other people who may genuinely just not want to be here. I’ve heard there are other countries where there are supports set up for people who want to die… Even heard at one point of a place of that nature where people could go to get support in killing themselves that supposedly ended up not having people actually go through with it, because it provided such a valuable space for people to talk openly about their struggles and death and everything else. I actually don’t know if that place actually fully exists as it was described to be… But it sounds really interesting if it does.

-Sera

Report comment

I can respect that. I don’t really like the term recovery either, since I’m not in recovery from the ‘disease’ of addiction, I’ve really just ‘developed’ the tools to cope with life without a chemical chaperone. Many of the terminology we use is routed in the archaic and barbaric past of the psychiatric sciences. I certainly have no problem moving away from that. Just, not at the expense of framing these issues in a way that downplays the reality or further suppressing and excluding those we are supposedly trying to help. I’ve lived longer without my mother than I did with her, and her suicide is far from complete. And I’m not saying we shouldn’t try to help others or that I’m glad my mom is dead or that I wish I had been allowed to kill myself. I’m only trying to say that the reality is that if her suicidal ideation even was treatable, she likely wouldn’t have been able to access the treatment. I don’t think the system failed to stop her, I think it failed to reduce the harm her actions caused. It failed to give her autonomy. It failed to identify my brother and I as high risk and make any effort to address that. Until it was far too late. I watched my aunts and uncles argue over whether to dress my mother in a turtleneck or a scarf, to hide the markings on her neck from the leash. Nobody in my ASIST training thought about that. If we demonize suicide and somehow convince this person not to do it, at least for today, and we do the “warm handoff”… But he later does it anyways, what then? His family can’t have an open casket because he took a shotgun to the face. His family can’t say goodbye, because some self righteous 50 year old white dude told me to at all costs use MI to convince people not to kill themselves. I understand it’s not all black and white and sometimes you have to accept whatever small victories you can get but I can’t live with myself imposing such beliefs on the community. All of this to protect myself from a $500k fine? No thanks, I’m a millennial. Maybe then I’ll be able to file bankruptcy so I can get rid of the 6 figure student loan debt doctoral training in social sciences awards you with. And what about my license? Eh, I can get paid more cashiering at Whole Foods. At least with my morals intact, I can look myself in the mirror. I can tell my son what daddy does for a living and not be ashamed.

Report comment

Bricew

Thank you so much for your heartfelt and insightful comments here at MIA. I have read every word.

I hope you continue to participate here. For future presentation of your valuable comments and ideas here, could you please break the one long paragraph into multiple short paragraphs. This will make it much easier for weary eyes.

All the best, Richard

Report comment

Thanks, Bricew. I really appreciate your sharing all this along with your conviction to prioritize morals and ethics over the superficial “goals” our society sets (often to distract us from some of the more covert ones).

Report comment

Brice, I am so very sorry for the loss of your mother and then stepmother and then hard times seemed to have continued. You lived on and it was not stupid for you to help out others and your life narrative is so very important.

Kids need you.

The trouble is the system and it still there were some good things perculsting but they got shot down. Fritz Redl would be a good person to look up if you still work in residential treatment.

To all, there are two threads here that for me seem to be getting tangled.

There is the 911 and or mental health check and then separate the mandated reporting thread.

1) The world is made so that ANYONE can make a call to polic and THEY have to act on that call.

So after having a blowout in the family car with one of my teen kids who was beyond furious with me for IDK and drove down the street to fast. Well families always always be wary when there are teen drivers living on the street or. the guy who stops at the bar everyday after work. So the neighbors made a fuss, I apologized for her behavior because by that time she had taken the car and driven away. I walked into the garage and muttered to myself something about being a bad parents and because there had been a suicide in the tiwn -actually a relative and nobody in the neighborhood knew because she did not associate with me- I just had these words that came out because several days earlier the same kid who also was unaware of the family relationship Nrs so and so shot her self in the mouth and died.

On overhearing my comment which was ostensibly private the neighborhood said loudly I know what I will do. I will call the police. She had no idea of who I was in any shape or form.

And then the police came.

No consequences for her poor judgement and breaking of boundaries. None.

I was mortified.

This practice has a long history. Some people use it to create neighborhood wars. And now it can be a racist or whatever ism and done and cloaked in so called caring.Fear plays a role too-

It makes everything so much much worse for EVERYONE involved.

Then mandated reporting can be used to help or hurt by usually the mandated is for trained professionals with the emphasis on trained. With the breaking of the systems there are risks the trainings are done poorly and the CPS staff poorly paid, overworked, and not requiring any special degree or life wisdom – can be problematic in the investigation.

Children are a lifeline to the future. In the United States they are pawns for politicians and mere consumers for profit making corporations. And the abuse and neglect especially in certain groups- ah we are ruining heart , mind, and soul here.

So IDK issues all around. I will always trust a survivor of any corrupt system then one who claims human perfection.

We need leaders like you Brice who KNOW and create something like a phoenix.

Report comment

sera thank you so much for sharing this horror story. even though there is nothing to like about it – what i really enjoyed reading is the way you unmask this whole enterprise and expose it for what it is. my highlight are your precise portraits of griffs, steves and ashleys of this world. there are too many of them, they look young and innocent but cause serious damage that goes entirely un-documented. it’s time for them to be studied and microscoped for who they are instead of them being further equipped to study (and treat) us. the nightmare scenario that this all turned into is material and extreme but i have to say that it bitterly reminded me of far less spectacular, every day emotional and mental risk that entering such spaces can mean for us. some of us interfere with this daily in our attempts at dialogue and collaboration. i understand you didn’t go there to collaborate, but your account reminds me on some of my own experiences of working in so called collaborative research. i could write a novel about that but as that is my most frequent source of income, i kind of put the emotions away and do my best to focus on the ’cause’. but too often i find myself surrounded by steve, griff and ashley and even if all goes well and my perspectives even ‘win’ – too rarely i can afford asking myself wtf i am doing here. sorry to be this pessimistic by what happened to you gives a naked picture of the worlds there are in between humanity on the one side and what sells as ‘mental health care’ (in any format) on the other. this account is an awakening reminder of who rules at the end of the day, so thanks again for this sharp and detailed and greately written analysis, this is so important to remember.

Report comment

And what purpose did it serve for these ASIST folks to disrupt your life, violate your privacy, and cause the dehumanizing harm that they’ve become blind to from overexposure?

“The answer lies in power and dominance.”

I’m very sorry to hear about this happening to a person I respect (albeit from afar). I would call it shocking, but this framework of “help” and “safety” is very much the norm as we all know. Still disgraceful, considering the minimum humanity I would hope all people deserve to be treated with.

What you’ve written here has actually explained the problems of inefficacy (!!!) and exploitation of almost all of the many, many aspects of the current “suicide-prevention” paradigm that are so noxious to society, MORE clearly than I’ve ever read from any article explicitly about that topic… the way you’ve written this is very particular, subtle and powerful – an extremely valuable piece of writing that has the power to impact the system itself, and I’m sorry that it had to come from such circumstances.

I’m excited to see whose desk, and which publications, this story winds up on. I believe you’re set to light a rare, public spark on the mountain of clinical injustices and similar stories. Your writing is a gift – thank you, Sera. I’m sorry for the way things are, but as you know, there are a lot of us and we are bolder than most.

Report comment

Unfortunately there are lots of “sparks.” This mistake is in assuming this makes a difference when the goal of the media is to obfuscate, and that simply “exposing” something means that it will be stopped.

Report comment

I mean to say this particular writing is just right for a fairly mainstream outlet to publish; it’s not highly technical, and it makes a very pertinent point with the story. There are single articles and papers that can refute every claim of the system, but these are so direct that they naturally get snuffed out. This story is relatable, sadly, and Sera makes her point concisely and by illustrating how it went down. To the unfamiliar, it can even come off as morbid humor, a very popular thing right now in the media. Keep doing what you do, Sera.

Report comment

What you say makes sense, which is part of the problem. The so-called “mainstream” media don’t want people bonding with people like Sera; they prefer to portray us as “off our meds” and disjointed, emotional and impulsive in our thinking.

Report comment

I know plenty of people “on their meds” who act that way. I often was.

The Haldol and other crap made me too numb to speak often. But it did not make me more coherent or rational. Nor did it enhance my problem solving skills.

That’s how brain damage “helps.” 🙁

Report comment

The fact that many people “in treatment” continue to do (or START doing) what the “treatment” is supposed to prevent seems to be completely ignored or suppressed. You’d think that improving “symptoms” would at least be a minimum standard for effectiveness, but apparently, there are no such standards.

Report comment

“Compliance” is all that matters in “mental health.” I remember a study NAMI conducted (need to look it up) where they determined successful treatments solely by how many continued to stay drugged. The quality of life was irrelevant since they didn’t record it.

You can be miserable, vomiting uncontrollably, unable to speak or move without difficulty, and obsessed with suicide. But if you’re “meds compliant” no one gives a rip. And they’ll dismiss any suicides as “in spite of” never “because of.”

How convenient! 😛

Report comment

The title should be safe for whom. Whom is used in the object position and following a preposition.

Report comment

Speaking of “wellness checks” don’t forget to read this too:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2019/02/facebook-predicting-kill-yourself-wrong/#comment-149252

Report comment

Hi Sera, I have story that resonates with yours but from another jurisdiction. Not ready to share it yet publicly so how about you make contact? The link to your email above is not working.

Report comment

F*ck! I’m left handed! Darn, I guess I’m just predisposed 🙁

I think it is safe to say that I don’t feel very safe knowing ASIST has the job of keeping me safe.

Which reminds me of an old safe story… about The Little Safe…

The Little Safe wasn’t allowed to go pee unless other BIGGER safes we’re present in the toilet stall with her, that way the BIGGER safes could keep Little Safe, safe.

One day, Little Safe, after weeks and weeks of being unnecessarily kept safe by the BIGGER safes… finally had enough of their demeaning safety and senseless river analogies!

With her little combination dial spinning, Little Safe confronted the BIGGER safes, swinging open her little safe door so the BIGGER safes could see inside!

The BIGGER safes all gasped in amazement…

Little Safe smiled and spoke confidently, “See you disparaging BIGGER safes. I have all I will ever need tucked away safely inside me already.” Little Safe continued, “sure, sometimes I can’t always find what I need right away, and I have to do a little searching, but it’s in there.

Always has been, always will be.” said Little Safe.

“In fact,” Little Safes voice suddenly ringing like thunder!

“All of us Little Safes are actually GIGANTIC SAFES! And she instantly quadrupled in size. Towering over all the BIGGER safes who were now trembling, and needless to say they were not feeling very safe!

GIGANTIC SAFE’s voice shattered windows, cracked the ceilings and the walls.

“I fully realize,” her voice booming “that none of you are hardly the bedrock of intellect let alone able to understand a small fraction of the concepts I speak about.”

“You safe-a-philes are all alike,” continued GIGANTIC SAFE, while the walls crumbled and fell, “you approach so much in life from a place of safe ignorance and false sense of arrogance that you never truly learn anything beyond what you are conditioned to see and hear.”

As Little Safe returned to her customary size, “You see,” she said, in her normal safe voice. “We Little Safes can be BIGGER, and appear to be safe and in-control at all times too. We just don’t feel the need for illusions.”

“We know we are GIGANTIC SAFES” continued Little Safe. “You see, we’ve had no other choice in life except to grow, and the need to feel safe all the time, to waste space in our safes with all the answers to the inexplicable well, that would just make us small again.” She said in her sweet safe sounding voice.

“Oh, and Gary”… unexpectedly the Thunder returning to Little Safes voice!