The Soteria that Loren Mosher opened in Santa Clara, California in 1971 was housed in a cozy older home, and his thought was that this physical environment, which was in such stark contrast to the cold floors of a hospital ward, could be a place of healing for newly psychotic patients. The men’s Soteria that opened in Jerusalem in the fall of 2016—the first house in a budding Soteria movement in Israel—provides that sense of comfort and something more: there is, architecturally speaking, almost a magical feel to the place.

The older stone building is located on a small side street in the center of town, perhaps a fifteen-minute walk from City Hall and the walls of the Old City. After you are buzzed in, you climb a few steps and come to a small courtyard, walled-in and yet with the open sky overhead. The space feels both cozy and partly outdoors, and at night, residents and staff lounge about on couches and chairs. From there you enter the home’s common room, which is like stepping into a fanciful set for a Shakespearean play. The ceiling is two stories high, with staircases on each side leading to bedrooms and alcoves that look down on the common area, and on the left-hand wall there is a second-floor balcony protruding into the space, a feature so whimsical I nearly laughed out loud. I couldn’t think of a better setting, as the Soteria doctrine goes, for “being with” people negotiating extreme emotional states.

I visited the men’s Soteria several times in the middle of December, and the tableau that greeted me on my second visit was a typical one: a few men sat at a table eating soup, and nearby a younger man was idly hitting a punching bag hanging by the kitchen, while another was expertly—and joyfully—juggling a few balls. Soon someone was strumming a guitar that had been propped up in the corner.

In the middle of the comings and goings, I spoke to a slightly taller man, who introduced himself as God, albeit a very modern God, as he had formed a What’s App group for those who wanted to communicate with Him, and, if I understood correctly, with Jesus too. Once I had signed up, he promised me that although God spoke in Hebrew, he would translate his comments into English for me.

This did feel a bit like traveling back in time, as I had often imagined what Mosher’s Soteria might have been like, and while there are a handful of other Soteria homes currently operating in the United States and other countries, what is happening today in Israel is of a different magnitude. If this initiative succeeds, Soteria homes will become a centerpiece of Israeli psychiatry.

In addition to the men’s Soteria, a women’s Soteria is also now operating in Jerusalem, and three more “stabilizing houses,” which is the government’s name for this model of care, have opened in the last month. Two more stabilizing houses are in the planning stage. Media coverage of the two Jerusalem homes has been quite positive; the president of the Israeli Psychiatric Association, Haim Belmaker, is on the board of Soteria Jerusalem; and the director of mental health services for the Israel Ministry of Health, Tal Bergman Levy, has voiced her support. Meanwhile, the Lasloz N. Tauber Family Foundation, a prominent mental health charity in Israel, has provided financial backing for the Soteria houses, and at a December 19 conference in Jerusalem, Sylvia Tessler-Lozowick, the foundation’s director, set forth her vision for the future.

“Soteria,” she declared, “should be a first-line treatment” for newly psychotic people.

At that moment, I thought that surely Loren Mosher’s ears—even though he passed away years ago—must have pricked up.

The Path Not Taken

Loren Mosher was head of schizophrenia studies at the National Institute of Mental Health when he conceived of Soteria, and he set it up as an experiment that directly challenged psychiatry’s current practices. Younger adults experiencing a first or second episode of psychosis were alternately assigned to treatment-as-usual in the hospital or to care in the Soteria house, which was staffed by ordinary people (as opposed to mental health professionals), and where there was no immediate use of antipsychotics. It was only if people did not start to get better within a couple of weeks that a low dose of an antipsychotic would be prescribed.

“I thought that sincere human involvement and understanding were critical to healing interactions,” Mosher told me some years ago. “The idea was to treat people as people, as human beings, with dignity and respect.”

In the late 1970s, Mosher began publishing the results of his study. At the end of six weeks, psychotic symptoms in the Soteria patients had abated just as much as in the medicated patients. The home was effective as an acute-care antipsychotic, so to speak. Even more compelling, the Soteria patients were doing better at the end of two years. Their relapse rates were lower, and they were functioning better socially—more likely to be employed or attending school. In terms of their use of antipsychotics, 42% percent of the Soteria patients had never been exposed to antipsychotics at the end of two years; 39% had used the drugs temporarily; and 19% had used them continuously.

Although the results told of better long-term outcomes with this approach, the experiment was understandably seen as a threat to psychiatry, and the field’s response came fast and furious. Mosher was accused of cooking his results, and while Mosher could easily refute the charge—he had independent investigators assess the outcomes, precisely to protect against this sort of accusation—the damage had been done. Funding for the project was soon shut down, even as an NIMH review committee, in a private written review, grudgingly admitted that the experiment had proven to be a success. Not long after that, Mosher was ousted from his position as head of schizophrenia studies.

Today, looking back, it is easy to see that this was a splitting-in-the-road moment for American psychiatry. Soteria became the path not taken, with Mosher’s firing the equivalent of a Danger Sign placed at the head of the road. Any psychiatrist pursuing this path did so at his own peril. American psychiatry went barreling down its “medical model” road, and soon the public was learning that schizophrenia and other major mental disorders were illnesses caused by chemical imbalances in the brain, which could be treated by drugs that fixed those imbalances, much like insulin for diabetes.

It is also possible today to see where the road not taken might have led. There is an obvious connection in spirit and practice between Soteria and the Open Dialogue therapy developed in the early 1990s in northern Finland. That approach emphasizes treating newly psychotic people outside the hospital; antipsychotics are used much in the same manner as they were at Soteria; and dialogical therapy provides a gentle way of “being with” those in psychotic states. And today, their long-term outcomes are, by far, the best in the Western world. At the end of five years, 80% of their first-episode patients are asymptomatic and working or back in school.

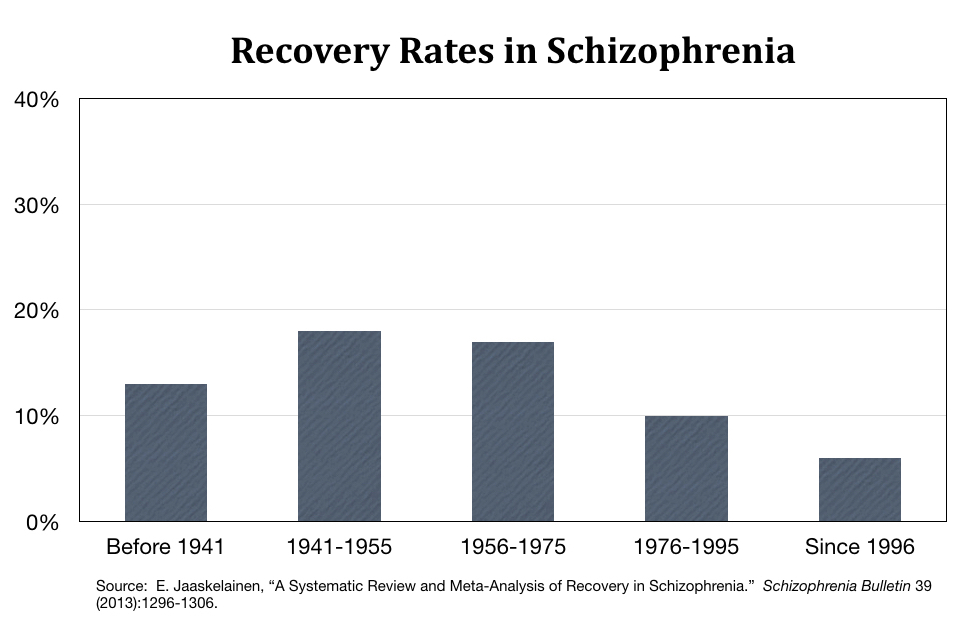

However, American psychiatry—and in essence, global psychiatry—went down a different road, and that has led to a different end. A 2013 meta-analysis found that long-term recovery rates for schizophrenia patients have been slowly declining since the 1970s, with recovery rates since the arrival of the atypical antipsychotics the worst ever, even below the rate in the pre-antipsychotic era.

Reviving Soteria

Anyone who knew Pesach Lichtenberg in the 1990s would not have pegged him as a psychiatrist likely to pick up Mosher’s baton and revive the Soteria experiment. After immigrating to Israel from the United States in 1986, he became head of the men’s inpatient ward at Herzog Hospital in Jerusalem, where he participated in the clinical studies of risperidone. He was certain that the new drugs coming to market represented a great advance in care, and in 1998, he left the hospital for a time to work for Israel’s Ministry of Health, where he oversaw the provision of second-generation antipsychotics to the hospitals.

“I was part of the general enthusiasm,” he said. “I thought the problem of mental illness could be solved.”

However, he also had a background in philosophy, which lends itself to questioning what one “knows to be true,” and Haim Belmaker had also placed a bug in his ear: “We are all so enthusiastic,” Belmaker told him, “but let’s wait a bit until we see the side effects of these new medications, because who knows.”

Over the next few years, disillusionment gradually set in for Lichtenberg. Studies that weren’t funded by pharmaceutical companies found that the new drugs were no better than the old ones, and as for hospital care, what helpful therapy did that setting really provide? There might be 50 patients for every staff person, which allowed little time for therapeutic contact, and patients at his hospital spent long stretches of time bored or in solitude. At times, he had to write orders that put patients into isolation or “even tied down to the bed.”

“I had a growing awareness that things aren’t as good as we like to believe,” he said, and with this discontent brewing, he became curious about the placebo effect. He read Irving Kirsch’s articles about how antidepressants barely beat placebo in the clinical trials, and he began exploring how other modalities of care—homeopathy and psychotherapy, for instance—worked through the placebo effect. What could be done, he wondered, to exploit the placebo to its maximum? Couldn’t a different setting help achieve that?

“I began imagining the possibility of a different psychiatry, a noninstitutional environment free of stigma and able to encounter the psychotic person,” he said.

Although Lichtenberg wasn’t aware of Soteria when his thoughts underwent this radical change, Belmaker, who had been at the NIMH in the 1970s, told him about Mosher’s experiment, and an obsession was born. He wrote his first plan for creating a Soteria in Jerusalem in 2004, and then spent the next 12 years trying to turn it into a reality. He spoke about his dream at conferences and public meetings, seeking financial support, and people repeatedly said that it was a nice idea, but that pat on the back didn’t turn into money. At one point, the Israeli government promised it would support a pilot project, but then that fell through, and at last a former patient of his, Avraham Friedlander, who was also involved in trying to make Soteria happen, put him on the proverbial Freudian couch. Did he really want to do this, or did he just want to talk about it?

“I was very disturbed by the question,” Lichtenberg said. “I was sure I wanted to do it, but why the hell wasn’t it happening?”

That was in the first months of 2016, and then a national scandal in Israeli psychiatry broke out. A morning radio talk show host told of a patient in a psychiatric hospital who had been tied up for 19 consecutive days, and each morning she added one more day to the tally. More ex-patients came forward with stories of abuse, and with the public now questioning the hospitals, Lichtenberg decided it was now-or-never time. The Tauber Foundation agreed to provide financial support; Belmaker joined the board of the non-profit he had set up; and he decided to ignore a lawyer’s warning that if anything went wrong at Soteria, “I would lose my property, my license, and my freedom,” he said.

In late July, one of the non-profit’s board members said she and her husband were moving to Canada for a year, so why didn’t Soteria rent their place? Lichtenberg told Friedlander they needed to have the house open by September 1.

“The image in my head was of Nachshon, who in rabbinic legend had dived into the Red Sea before it parted, in an act of faith which forced God’s hand,” he said.

“Being With” in Soteria Israel

The notion of “being with” is the core therapeutic principle of a Soteria house. The understanding is that psychotic thoughts and voices—rather than being seen as symptoms of a disease—might be meaningful, and thus do not need to be squashed. The role of staff is to listen and, in some manner or another, participate in experiencing the psychotic state in a non-judgmental way.

This sentiment, it was easy to observe, permeates the men’s Soteria in Jerusalem, but within a cultural context that provides, as Lichtenberg says, “a Jewish spin.”

The Story of Avraham

The clinical director of the house, Avraham Friedlander, is an adherent of Orthodox Judaism. Everyone calls him Avremi, and as he moves through the house and speaks with residents, he radiates a gentility and kindness, along with a firmness in thought and action. He also brings lived experience—of a particular religious kind—to the job.

More than a decade ago, when he was in his early twenties, he immersed himself in Kabbalah teachings, an ancient Jewish mysticism. “From this learning,” he recalls, “I started to travel in other worlds . . . I thought I am a prophet. I saw people, I saw colors, and I wasn’t afraid, because I wanted to see.”

He was now the “soul of Abraham,” and after a Rabbi told him that the Messiah would not come until someone “really, really wanted him to come,” Friedlander decided he would show God that he was that person. After many days of prayer, he knew that the day had arrived, and he went to the Holy Wall in Jerusalem, carrying a white robe for the Messiah to wear. However, after praying for some time, “nothing is happening, and it is very strange to me,” he recalled. “Why is the Messiah not coming?” He suddenly thought of the Biblical stories of Joshua and others who told God they would not budge until He answered their prayers, and so he dropped to his knees and told God “I am not moving, I am not talking to nobody, I am not looking at anybody, I am not eating, until I see the Messiah.”

“I didn’t want to force God,” Friedlander said. “I did it to show how serious I am. How really, really, I wanted the Messiah to come. But he didn’t come. And I was in trouble, because I had made a vow. I cannot talk, I cannot speak, and I cannot eat.”

An ambulance took him to Herzog Hospital, where the staff diagnosed him with catatonia. He awoke that night in an isolation room, and briefly broke his vow in order to find a common phone and tell his wife where he was, and inform her that “from now on, I won’t speak, never.”

The next day, the ward psychiatrist—this was Pesach Lichtenberg—wheeled him into a doctor’s meeting. However, rather than tell his colleagues about this new patient’s catatonia, he instead provided Friedlander a “being with” moment. “Pesach,” Friedlander said, tells them “he feels that I am with him, he feels that I am not catatonic, he feels my breathing, that I listen to him, that I feel him, and maybe he sees this also in my eyes. And then Pesach starts to talk to me, and he says you can go back to your room, and because he is an authority, I was able to go back to my room. I stand and go back, but because of my vow that I am not supposed to walk, Pesach is shocked, because I am walking.”

Soon, his wife brought a Rabbi to the psychiatric ward, who said he needed to hold a ceremony to let Friedlander break his vow. The ceremony required three people, and Lichtenberg—in another moment of “being with”—participated as one of the three.

“I opened my eyes,” Friedlander said, “and I started to talk and I was a normal person, and the hospital said, ‘it’s a miracle.’ They had never seen a catatonic man return to life, from one minute to the next, and thank God to Pesach that he agreed to allow the Rabbi to give me the ceremony.”

This was Friedlander’s experience as a hospital patient, and not long after the men’s Soteria opened, he had the opportunity to “be with” a resident in much the same manner that Lichtenberg had been with him. One of the first residents at the house—and this was a time when Friedlander’s wife and children often stayed there with him—lay down, “locked to the floor.” There was no way he could stand, the resident said, unless someone could find “rice” to open the lock.

“I told my child, please go to the kitchen and bring me rice, and he brought me rice, and with the rice I opened the locks, and he got up,” Friedlander said.

The Turkey Prince

In Rabbinical teachings, there are many stories that lend themselves to this practice of “being with.” The one that Soteria Israel has adopted as a guiding moral is that of the “turkey prince,” which was told by a Jewish mystic at the turn of the nineteenth century.

In this tale, a prince is convinced he is a turkey, and so he sits naked under a table and picks at crumbs on the floor. Nobody knows what to do, but finally a wise man comes. After a moment of contemplation, the wise man proceeds to take off his clothes and sit with the prince under the table. He is a turkey too! This goes on for a while, but then the wise man tells the prince he is cold; would it be okay if they got some clothes? He would of course still be a turkey! Then the wise man says turkeys can do better than eating crumbs from the floor; would it be okay if plates of food were served? Finally, the wise man says his back hurts from sitting under the table, and so would it be possible for them to sit at the table and eat? And with the prince clothed once more and sitting at the table, he was restored to his old self.

Today, Lichtenberg and Soteria staff can tell many stories of “being with.” One of their first residents would relieve his anxiety by letting out a “blood-curdling scream”—after this happened several times, they decided they would all join in, everyone sharing a “protracted shriek.” Afterwards, everyone “felt relief,” Lichtenberg said, adding that the staff at the men’s house, when a “being with” moment presents itself, will often say, “maybe you should turkey him.”

I got my soul back

Naturally, I wanted to hear from the residents about how they were experiencing this “being with” environment, and there was one resident—a burly, rough-edged man—who was particularly keen on telling me his story. However, he asked that I not print his name, evidence of the stigma that exists, in this country as in others, around “mental illness.”

A middle-aged, divorced father of two, he had suffered a psychotic break of sorts six weeks earlier while strung out on high doses of benzodiazepines. He had acted out aggressively at work, and by the time he arrived at Soteria, he was hearing voices and suffering extreme anxiety attacks. During his first days here, he often behaved in a threatening manner.

“If I had gone to the hospital, I would have been completely drugged,” he said. “My old head didn’t work. I had emotions gushing out, I was crying, shouting and angry when I came here, and I broke pots, I broke chairs. But they were just with me. They just let me let it out. The love was still there, and nobody came and grabbed me and threw me out. And from there, I started an unbelievable journey.”

Under Lichtenberg’s guidance, he gradually tapered from the benzodiazepines, and quit his marijuana habit too. Soteria, he said, was “full of hugs,” and during his six weeks he had gone through a transformation: the angry, violent man he had always been dissipated, and a softer person appeared.

“I could be emotional here, I could be sad, I could be sensitive,” he said. “After a week and a half, I felt my soul was becoming free. I was dancing, like in a trance listening to music, and no drugs, and I went into a happy place. The love, empathy, and acceptance allowed me to be who I am. I am a sensitive man, and it was not possible for me to be that in my world before.”

He would be leaving the house in a couple of days. “I still have a long journey ahead of me, but I am excited for it,” he said. “I found my inner truth, talking from inside my heart and not from my head. This is me, and it’s okay.”

Daily Life in Soteria Jerusalem

The men’s house has nine beds, and at the moment, all of the residents are private-pay, as the country’s four HMOs have yet to approve payment for Soteria care. There are three or four professional staff, a house mother, and 15 “ordinary staff,” about half of whom have “lived experience.” There are three staff at the house at all times. A dozen or so volunteers, including several former residents, come by regularly to help out.

There are no scheduled therapeutic routines in the house. The house mother prepares a daily soup, all the food is kosher, and there is always fresh hummus, made from Lichtenberg’s own recipe. The residents are expected to help prepare food, clean up their dishes, and otherwise help with the chores needed to keep the house running. There is no formal psychotherapy at the house, and the group talks, with everyone sitting around in a circle in the common room, are more like house meetings common to communal living, with no requirement for anyone to attend.

The most controversial aspect of the house, at least from the perspective of many of the residents, is that the front door is locked. When the house first opened, the plan was to leave it unlocked, with residents free to come and go, but on the very first night, one of the residents went out and “almost got killed by a passing train,” said Shimon Katz, a social worker who has been here since day one. “That would have shut down the whole thing. We feel responsible to take care of the safety of the residents, and if they are not in a condition to be outside on their own, we want to be with them. We also have the responsibility for this project, this revolution, to work, and if something like that happens, the whole project is going to be shut down.”

Many of the residents do go out on their own, and the staff regularly arranges excursions—to the market, to a park to play Frisbee, or, more recently, to the desert to go hiking. However, there are residents who remain bitter about the locked door, and if the issue can’t be resolved, then the resident may leave, as everyone is here on a volunteer basis, Katz said.

While the house was quite calm the times I was there, the staff have had to deal with aggressive residents, and suicidal threats too. When someone is angry, Friedlander said, they do not respond in kind, but rather wait until the “person is cold. Then everybody talks about what happened, and decides whether the person can still be here, or, if it’s too much, we can take the person back to the hospital.”

This is the hardest part of running Soteria, he added. At such moments of crisis, they don’t have the mechanisms of control that a hospital does. “Somebody comes, and says ‘I want to kill myself,’ and we don’t have the power of authority, and sometimes people break things and want to hit people, and we don’t have an isolation room, and we don’t have a straight jacket, and we do not have the drugs, and so all this is very hard. What do we do? It’s personality, it’s our humanity that we have to use. We are hugging, we are breathing, we are singing, we are dancing, we are talking, we are being with, but it’s very hard.”

There was one instance, Katz said, that he suffered a minor injury when he restrained a resident who had begun physically fighting with his parents, who were visiting. At the same time, the staff has gained experience that makes it easier for the house to “hold” and “tolerate” difficult behavior.

“Do you see that person on the yellow couch,” Katz said, pointing down to the common room below. “He was a past resident, here for 2.5 months. He was one of the wildest residents we had. He decided he wanted to paint stone walls of his room, and he threw paint all over like Jackson Pollock, and he urinated at the entrance to Pesach’s [private] clinic downstairs, and he broke three guitars and an oud, and we weren’t sure we would be able to contain him because he was so wild. He would spit everywhere, and if we were meeting, he would take over. But he came out of that—initially he was a little dysphoric, a bit shut down—and then he came back up. We offered him to become a volunteer, and now, two months after ceasing to be a resident, you can see him teaching guitar to two other residents.”

Perhaps half of the residents arrive on psychiatric drugs, and the other half are newly psychotic patients and med free. Many arriving on psychiatric drugs want to discontinue them, and while Lichtenberg may prescribe a drug if he thinks it could be of benefit to a resident, the general thought is that drug tapering can be a positive step toward recovery, with getting off all medications and doing well a particularly good outcome.

As such, Soteria Jerusalem regularly has residents experiencing drug withdrawal symptoms, and the house needs to provide “something else” to help them cope with those difficulties, Katz said. “We have to be with them physically and metaphorically, holding the person’s hand in the night or the day, or singing a lullaby if they need to fall asleep. Or maybe it’s body work, massage, or holding, or hugging a person—these things are alternatives to pharmaceutical drugs and they work. We also teach people how to breathe, and to not be frightened or scared when they feel a bit anxious, and we teach them how to observe it from the outside. We teach them these kind of tools.”

One person who went through this withdrawal process, Asher Leibovitz, now works here as staff. A 38-year-old father of three, he had a good record working in construction, but in recent years he had begun to suffer emotional outbursts. Four time he had checked himself into a psychiatric hospital, and this past fall, after a particularly horrible panic attack, a family friend recommended that he come to Soteria, rather than go to a hospital. He arrived taking 12 psychiatric pills a day, and while the first two weeks of his drug taper were very hard, after six weeks he had gotten off all the drugs. “I will never go back to using those pills. I can think better now,” he said.

The staff I spoke to all told of how they “loved” to work here, finding it both fascinating and rewarding.”The excitement and gratification are invigorating,” Lichtenberg said. “Of course there have been frightening moments, especially at the start, when we didn’t quite know how to do this work and I found myself nostalgic for seclusion rooms and muscular orderlies. An undertone of anxiety is ever present, in anticipation of the inevitable tragedy which is part of our work, but which could undermine so much of what we’ve accomplished. But all in all, after over 30 years in the profession, I’ve never enjoyed my work so much.”

The final staff person I spoke to was perhaps the last person I expected to find working here. Sharon Goldberg is an adherent of Orthodox Judaism, and as such, she is expected to refrain from touching men, except for her husband. Yet, she has been working for 15 months in a residential home that, as everyone often remarks, specializes in giving hugs.

“This was a very central issue for me from the beginning, and not only in a physical sense, but also in an emotional sense,” she said. “It’s just natural that the residents here feel lonely and they long for a relationship with a woman, emotional and physical, and it’s always a challenge, because my job is to get close to them. So usually I won’t give hugs. They understand and sometimes it’s part of the negotiation about our relationship. I sometimes say, my job here is to give many things, but not hugs. I am not here to physically touch. Many times I say that I hope my care and love can be felt without the touch.”

Soteria, Goldberg said, is a place of learning, growth, and questioning of boundaries for both staff and residents. While the residents have all been Jewish so far, the hope is that one day that there will be Arab residents too.

“The house, I hope, can welcome everyone, and it is also interesting that each resident and each staff member changes the dynamics and atmosphere in the house. It’s really easy to see it, in the energy and the relationships, it is amazing. The house is always breathing.”

Rethinking Antipsychotics

The launching of a Soteria movement would not necessarily be seen as “revolutionary,” or as a “paradigm-shifting” event, if it simply involved treating psychotic people in a home-like environment. There has been a long-standing international effort to move psychiatric treatment out of the hospital and into the community, and if the Soteria initiative were accompanied by regular use of antipsychotics—and this is how many innovative social programs for psychotic patients in recent years have dealt with the medication issue—then mainstream psychiatry could mostly shrug its shoulders and move on. The medications would still retain their position as the cornerstone of care.

At first, that was somewhat the story told to the public when Soteria Jerusalem opened. Media stories focused on the humanistic environment, and if they made mention of antipsychotics and other drugs, they simply noted that antipsychotics had been downgraded in importance, or that patients would have a choice on whether to take them. Those stories didn’t tell of the possibility that the drugs may be a barrier to recovery, which was one of the conclusions drawn by Mosher.

That has now changed. There is a discussion that has opened up within Israeli psychiatry, which has spilled out into public venues, about the merits of antipsychotics, particularly over the long term. The discussion has been generated in large part by a high-tech entrepreneur, who asked that I only use his first name, Gadi, and his wife Ruth. And once they planted the seed for this discussion, it has been taken up, in a surprising way, by Belmaker, president of the Israel Psychiatric Association.

Introducing critical psychiatry texts to Israel

As might be expected, Gadi’s and Ruth’s activism arose from a personal experience with conventional psychiatry that didn’t go well for their family. One of their teenage sons became anxious and depressed while doing a year of community service, which involved living away from home, and two weeks after being put on an antidepressant, he developed manic-like symptoms. Thus began his fall into the medication rabbit-hole. He was taken off the antidepressant and switched to an antipsychotic, risperidone. On that drug, he suffered from akathisia, and so his psychiatrist switched him to olanzapine, and on that drug their son “suffered from hallucinations, inner restlessness, and zombie-like behavior,” Gadi said.

The psychiatrist told Gadi and Ruth that their son needed to be hospitalized. But having seen their son get progressively worse under psychiatric care, they rejected that advice, and instead decided to help their son taper from the medication. As they did so, they immersed themselves in critical psychiatry books, and suddenly they began seeing their son’s difficulties through that lens, as opposed to the chemical imbalance story they had been told when their son first saw a psychiatrist. Their son’s “power” began to return as he tapered from the medication, Gadi said, and he began to play music again and engage socially with others. After six months, his son was totally off psychiatric drugs, and “we had our son back.” His son soon started academic studies, and today “enjoys a very vibrant social life and political life.”

That might have been the end of it, except that Gadi and Ruth, having found the critical psychiatry literature so helpful to their family, “felt committed to share this knowledge with other families in Israel.” They began thinking of starting a Soteria project in Israel, only to discover, much to their delight, that Lichtenberg would soon be opening a Soteria house in Jerusalem. Gadi quickly joined the board. At the same time, Gadi and Ruth wanted to introduce critical psychiatry texts to Israel’s Hebrew readers, and this is how I came to this story: they engaged an Israeli publisher to translate my book Anatomy of an Epidemic, given that it challenges, in what they saw as an evidence-based way, the long-term merits of antipsychotics and other psychiatric drugs.

This “critical psychiatry” perspective is new to much of Israeli society, Gadi said. “Although Israel is quite advanced in its social support and rehabilitation programs, a lot of the energy of activists went into that, rather than focusing on changing the core of the biological paradigm. Israelis also treat their doctors as ‘mini-Gods,’ and up until recently were unlikely to challenge their views.”

Given his work as a high-tech entrepreneur, Gadi is experienced in launching new businesses, which includes marketing new ideas to the public. He and Ruth successfully got media attention for this challenge to psychiatric drugs; they set up or helped organize several public events; and most important, from my point of view, they arranged for me to meet Belmaker and other psychiatrists that would be open to talking about the long-term effects of psychiatric drugs. This was reaching across the aisle, so to speak, which can be so very difficult.

While Gadi knows that the Soteria initiative is in an “early-development” stage, he brings an entrepreneur’s confidence to this effort to create wholesale change in psychiatry in Israel and beyond.

“With Israel’s high-tech success, we’ve seen Israel startups changing the world—Waze, Mobileye, etc.—and gained confidence in our abilities,” he said. “And like any high-tech investment, the key is always the team and the entrepreneurs. When we met Pesach and Avremi, it was clear that this is the team we want to back.”

Agent of change

There is perhaps no better known psychiatrist in Israel than Haim Belmaker, and given his career, he, much like Pesach Lichtenberg, would seem to be an unlikely candidate to promote a rethinking of the use of antipsychotics and other psychiatric medications. Belmaker, who grew up in Brooklyn, is known for having brought “biological psychiatry” to Israel when he immigrated here in 1974, and when criticisms of psychiatry have arisen in Israel, he has often been the public defender of his profession and its treatments. His CV tells of his having served on the editorial boards of Biological Psychiatry, the Journal of Neural Transmission, and Bipolar Disorders; he has received research awards and prizes from NARSAD, the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry, and the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology; and he has been the president of the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology and the International Neuropsychiatric Association. He became president of the Israel Psychiatric Association in 2015.

However, even before I came to Israel, I knew of his name because of an obscure letter to the editor of the British Journal of Psychiatry he’d written in 1977, which told of an ability to see the drugs through an unorthodox perspective. In it, he described the reactions that he and a colleague had to taking a dose of haloperidol.

“Each subject complained of a paralysis of volition, a lack of physical and psychic energy. The subjects felt unable to read, telephone or perform household tasks of their own will, but could perform these tasks if demanded to do so. There was no sleepiness or sedation; on the contrary, both subjects complained of severe anxiety.”

That letter told of an open mind, and as Belmaker confessed in a later interview, he also discovered, early in his career, that initial findings in biological psychiatry often do not stand the test of time. “It has influenced my whole concept of science ever since,” he said. “One of our major problems in psychopharmacology is that a large percentage of what we find can’t be replicated. Sometimes, this is so even with excellent work that was done with the best of intentions. I don’t think we have dealt with this as a field.”

Those experiences may help explain why, decades later, he cautioned Lichtenberg about getting too excited about the second-generation antipsychotics, and told him too of Mosher’s Soteria work. And during my ten days in Israel, I watched his thinking continue to evolve.

One evening shortly after I arrived, I gave a very short talk about Mosher’s Soteria experiment at a dinner gathering. The next day, as he led me on a walking tour of Old Jerusalem, he said that what he had been learning about Mosher’s Soteria experiment, together with what he was hearing from staff and residents at Soteria, was leading him to think anew about the possible hazards of long-term use of antipsychotics, at least for some patients.

He echoed that thought at another dinner several nights later, a gathering that included several directors of mental health services for Israel’s HMOs. He didn’t just urge his colleagues to be “open-minded” about discussing the merits of psychiatric drugs, he suggested that the time was ripe for thinking about new paradigms of care. I felt like I could hear the wheels of change spinning, and afterwards Ilana Kremer, director of psychiatry at a hospital north of Tel Aviv, asked that Gadi and I come to speak to her staff, and by the end of that day, she and others at the hospital were excitedly talking about creating a Soteria project of some kind as an adjunct to their institution.

Finally, on one of my last days in Israel, I spoke at a conference in Haifa that the Israel Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association had set up as a debate of sorts. I would present the case against antipsychotics, and Donald Goff, a well-known schizophrenia researcher in the United States, would present the case for the drugs. Goff had been the lead author on a paper published last spring in the American Journal of Psychiatry that was designed to refute those of us who had written critically of antipsychotics, and so I expected the day to be contentious. Yet, at day’s end, Belmaker, much to my surprise, had found a common element in the presentations, which was that both could be said to have made a case for selective use of antipsychotics.

“In the next few days, I will appoint a committee to develop guidelines for lowering medication doses for schizophrenia patients, and deciding on which patients might be appropriate for stopping (the drugs),” he told me immediately afterwards. “These guidelines will not determine treatment, but they will allow psychiatrists who might be afraid of the medical legal consequences of doing a practice that isn’t standard, and of being sued for that, to start thinking in this direction.”

There was a changing of the guard underway in Israeli psychiatry that made this a particularly propitious time for rethinking the use of psychiatric drugs, he added.

“About half of the psychiatrists in Israel are over age 60, and many of them came to Israel in a large wave of immigration that occurred with the breakup of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. I can say, very honestly, that they came from an authoritarian culture that didn’t have the psychotherapeutic, anthropological norms that anyone growing up in North American or Europe had as their cultural background. Their approach to data, and data analysis, and their ability to absorb a paradigm shift—one that comes partly from the public in its demands, rather than from authority—is much less than those who have gone to medical school in Israel. Many of them will be retiring soon. But the people you have been meeting will be quite open to new ways of thinking.”

Shortly after I returned to the United States, Belmaker made good on his word. He appointed Lichtenberg and three other psychiatrists to a committee to develop such guidelines, which, he wrote, would provide the “legal and moral defense of a psychiatrist who, in his judgment, wants to reduce dosage or make a discontinuation attempt.” Marker magazine, a general interest publication in Israel, reported on this startling development, reporting that Belmaker also advised his colleagues “to stop claiming that we know the pathophysiology of psychosis and depression through serotonin and dopamine, and to admit that we treat symptomatically and do not always succeed.”

Perhaps, I thought, one day this would be the shot heard ‘round the psychiatric world. With this initiative and Belmaker’s directive, Israel is pulling up the “Road Closed” sign that American psychiatry had placed on the Soteria path decades ago, and declaring it open for exploration anew.

Stories of Transformation

The women’s Soteria in Jerusalem opened in October of last year, and it is located in one of the nicer neighborhoods of the city, perhaps a 20-minute walk from the men’s home. Although the house doesn’t have the same magical architecture as the men’s does, it has a homey feel, with the kitchen and adjoining living room a relaxing area to hang out. A sun-dappled backyard provides a quiet refuge.

This was the one time I got to see Lichtenberg interact with the residents, and what was so noticeable was how relaxed and open they were with him. He has a gentle, self-effacing manner of “being with,” both in terms of how he listens and offers advice. He often lightly teased the residents, which usually elicited an appreciative smile or a joyous laugh. “They can’t believe that Pesach is a psychiatrist,” said Tova Ofek, the house mother.

The four women residents that told me their stories all asked that I not use their real names. While the details of their stories varied, there was a common theme in terms of their experiences at Soteria.

Hospitals

Soteria is meant to serve as an alternative to hospitalization, and all four women had been hospitalized before, where—and this was their biggest complaint—they had been heavily medicated. “Ask me which drugs I didn’t take,” said one woman, who had been hospitalized multiple times. “Most were worse than the one before.”

The women all told of how the heavy drugging, first in the hospital and often after their discharge, had negatively affected them. They told of being cognitively slowed, apathetic, anxious and physically impaired on the drugs. One woman who had been a dancer all her life grew quite heavy on an antipsychotic, and, some weeks earlier, when confronted with going back to the hospital, she had planned her suicide. “For me, the choice was psychiatric hospitalization or death, and a psychiatric hospital was worse than death,” she said. “If there hadn’t been an alternative (Soteria), I would be dead.”

As a group, their complaint was not necessarily against medication, but rather against the heavy drugging they had experienced and observed in their fellow hospital patients. “Here in Israeli hospitals, people are drugged to death,” one resident said. “Women much younger than me can hardly move. They gain a lot of weight. They don’t function. They are sleeping with diapers. Life seems really hopeless.”

The Soteria experience

The four women, whom I’ll call Aliza, Nicola, Natalia, and Miriam, knew little about Soteria before coming here. Usually it was a family member that had become aware the house had newly opened, and they told of being slightly disoriented when they first arrived, simply because it was so different from the hospitals they had known. Could this place be real? But then—and this was the recurring theme in their stories—they started to feel safe here, and that’s when they began to feel better. They had all tapered down from the medications they had been on, with one of the four women off psychiatric medications altogether, and they all said this was an important part of their coming “back to life.”

Aliza is 26 years old, and her struggles in the outside world had begun three years earlier when she moved to a new town and quarreled with her new neighbors. They started calling her “horrible names,” with one man threatening to kill her. “My body got hurt,” she said, “my internal parts got hurt.” Those voices continued when she arrived at Soteria, and during the first nights, “while I slept, they hurt my body.”

The staff asked her if she could find a room in the house where she would be safe, and that proved to be the turning moment for her. “Things are feeling better,” she said. “I hear people talking less bad about me. I am not as afraid of being hurt.”

As for medication, she had tapered down to a small dose of Abilify. “Here I get proper medicine,” she said. “They are attentive to my needs and they listen to whatever I need. They see the person . . . I feel like people here care about each other. I am surrounded by love.”

Nicola, who is in her mid-fifties, had tried to commit suicide several months earlier, and after spending time in a hospital, came to Soteria the day it opened. “I was completely despondent because of the pills, and when I first got here, I didn’t go out,” she recalled. “The place was confusing. There is so much love from the staff. Everybody is hugging and kissing you. It is the antithesis of the hospital. It is hard to adjust to something good like this. You have too much freedom. You can think about what you think about, and nobody gives you a shot or ties you up.”

That was six weeks ago, and she was now down to a small dose of perphenazine and a Valium at night to sleep. The “sleeping pill” would be the next to go, she said. And having adjusted at last to this “loving” environment, she now regularly ventured out and was even taking a dancing class, her mood change so dramatic that Lichtenberg could not help from quipping that she was becoming “hopelessly optimistic.”

“I feel like a new person,” she said. “I feel like I have been reborn. I got my self confidence back.”

Natalia, who is in her mid-thirties, immigrated to Israel from Russia, coming with her family when she was seven years old. The story that she tells of her life since then is one of almost relentless suffering: being bullied by other kids in school, domestic violence at home, and years of sexual abuse, starting when she was barely a teenager. After a suicide attempt in her early 20s, she began taking psychiatric drugs, losing herself every evening in a haze of Xanax, Clonix, wine and Ambien.

Like Aliza and Nicola, her first days at Soteria were difficult. “I couldn’t sleep, and I started to hallucinate,” she said. “But about a week ago, it was the middle of the night and I had a wonderful conversation with a beautiful 23-year-old worker. I felt at that moment like I fell into a rabbit hole, a parallel universe. For the first time in my life, I can break down, I can cry, and I can cut myself, which is my defense mechanism. They just took care of me and sat with me. I felt so accepted, and they hugged me. I am a person with a dire need for love and acceptance, and here nobody labelled me. You can just be yourself, and it’s okay, and they will be here for you, no matter what state you are in.”

But, she said, she was still struggling to believe this place was real. “This feeling is so new to me. I don’t know how to process it. I didn’t believe in my wildest dreams there could be a place like this, and people like this.”

Miriam, who is 32, had come here with one goal in mind: to get off antipsychotics. She had first been put on psychiatric drugs when she was 17, and she had come, in particular, to hate antipsychotics. “The pills feel like a Holocaust, and they are like Auschwitz, and they bring the world down upon us. I used to pray to God that He would help me get better without medication.”

She’d had her last antipsychotic shot three weeks before coming here, and Lichtenberg hadn’t prescribed any continuing drug treatment. “I don’t have to worry about Pesach,” she said. “He is good at not giving you medication.”

However, being off medication was turning out to be slightly unsettling for her, but for an unexpected reason. She is a voice hearer, and in the past she has had an ambivalent relationship with those voices. “Without medications, the voices will be good to me,” she explained. “With medications, the voices start cursing me and saying dangerous things. It is only the medication that made me want to commit suicide.”

However, this time, after several weeks off medication, “I stopped hearing voices. I felt something was wrong. Now that I am without the psychosis, I feel a bit dead. I am nostalgic for the psychosis.”

Even so, she was beginning to understand what she wanted from being at Soteria, besides getting off meds. “Because of all the psychosis I have known, I have been very confused. And now I want to know, who am I beyond the psychosis?”

Returning to the outside world

The four women had all told of suffering in the outside world—of loneliness, violence, sexual abuse and taunting voices. At Soteria, they had found a safe haven, and when I asked them about their leaving here, they mostly told of being afraid to do so.

Aliza feared her neighbors would begin yelling at her again, telling her “you are crazy, that is what you are.” Miriam said that out in the world, “people are often undressing me, and I need my clothes,” and so she would need to come back here. Natalia wasn’t even willing to consider what lay ahead: “My only goal now is to stay in this rabbit hole, this wonderland. I want to stay in this safe place.” Only Nicola expressed some confidence in leaving, but part of the reason was that the staff had urged her to return as a volunteer. “I feel really flattered by that,” she said.

Anecdotal results

These four stories, of course, all fall into the “anecdote” category, which are understood to be of little importance in “evidence-based” medicine. They also tell of momentary snapshots, of how the four residents felt about Soteria on the particular day I spoke with them. Their perceptions can easily change, and indeed, a week or so after my visit, Natalia sent me an email saying she was now being “bullied” and that was the “truth” of the place.

But the staff here, for their part, are confident that the Soteria house is working. “What I can see, in the women’s house, is that the people start to talk about what is inside, and we hear them, and suddenly they feel better,” said Ofek, the house mother. “We listen to them, we don’t judge them, and it happens in days. It is like a miracle.”

Hurdles Ahead

Although there is growing public support for Soteria in Israel, thanks in large part to the positive media reports, this initiative is still very much in its infancy, and there are two evident hurdles that must be surmounted if “stabilizing homes,” as the Ministry of Health is calling them, are to become a first-line treatment for those who otherwise would be hospitalized. The first is that many psychiatrists are resistant to this “paradigm shift,” particularly the questioning of antipsychotics.

“There is a certain suspicion among some of my peers that I’m undermining their work or threatening their prestige,” Lichtenberg said. “But I’ve been delighted to find how many psychiatrists, especially but not only among the younger ones, are open to new messages. And I’ve invited hospital heads of psychiatry to collaborate. It’ll take time, but I expect that it will happen.”

The second hurdle, and this is a more immediate one, is making the case to the Ministry of Health, and to the four HMOs, to pay for this care. While the government sets a national budget for healthcare, the HMOs have some decision-making authority on how the dollars are spent, and in this era of tight budgets, this means that different patient groups—cancer, cardiovascular, psychiatric, etc.—are in competition for these funds.

“I would be happy if HMOs began paying for this, and I am saying this out loud. But I can’t make them do it,” said Bergman-Levy, head of mental health services at Israel’s Ministry of Health. “However, I can be supportive and if I persuade my director general that this is something that should happen, there can be a directive from the regulatory ministry that this is something you must have. So maybe I can be persuasive in that way.”

At the moment, the two Jersulaem homes rely on private-pay patients for most of their revenue. The cost is $5500 (U.S.) a month, which limits who can come and how long they stay. Even this payment is $2000 short of what Soteria needs to cover its expenses, and thus, at the moment, the homes are relying on financial support from the Tauber Foundation and other private donors to operate.

The case that needs to be made, Bergman-Levy said, is that Soteria care is cheaper than hospitalization, and at least equally effective. The cost argument can be easily made, as hospital care costs around $9500 a month, but of course Soteria Jerusalem doesn’t have any outcome data yet. The treasury department will want to see how the residents fare after they leave Soteria, and, in particular, whether they go back to work. “If I can prove that it’s good for the patient and cost effective, then I will be able to get more support from the department,” she said.

Bergman-Levy, Lichtenberg and others all said that they knew that this initiative, which can be seen as a national experiment, will be closely watched by other countries.

“My hope is that once the HMOs finance the venture, Soterias—or stabilizing houses—will proliferate by the dozens, and people needing care 24/7 will demand treatment in such homes and not in institutions,” Lichtenberg said. “We are not far from the tipping point for that becoming the norm. On bleaker days, I wonder whether Soterias can survive in the long haul without the extraordinary devotion of so many of the people who make it such a special place. And, of course, I worry how Soterias will be once they become the standard of care. Will Soteria retain the freshness of its extraordinarily humane approach?”

Said Bergman-Levy: “I think we can be an inspiration to the world.”

Robert,

Thanks so much for this report on the Israeli Soteria houses; it’s good to know they can operate successfully in such a conservative country. It gives me hope that our politicians and insurance company executives in the US will start using their common sense and look at the lifetime recovery rates in the Soteria/Open Dialogue models vs. recovery rates under the current drug-pushing medical model that produces life-long disability payments for increasing numbers of people – who also get free medical care and pay no taxes.

I don’t have the know-how and resources (or years left) to do this myself, but I sure wish you or one of your equally knowledgeable peers would would get these figures together and publicize them. Seems to me it’s going to take hard facts like this to counteract the half-truths and lies spread by Big Pharma and its allies.

Best regards,

Mary Newton

Report comment

Removed at request of poster.

Report comment

So fuck Palestine? Israel is essentially an American outpost for imperialism in the Middle East, and occupied territory.

Report comment

OH, Are you quoting Mahmoud Ahmadinejad?

Report comment

Israel is the the historical equivalent of “Fort Apache” in the Middle East. It wouldn’t last a week without the hundreds of billions of dollars in foreign aid from the U.S. protecting its Imperialist interests in that region of the world.

Would it be accurate to call ancient Greece a democracy when it was built upon a foundation of slavery?

Richard

Report comment

Thank you, I was hoping I wasn’t alone here (even though most of the world would concur) — I was waiting to be called “anti-Semitic” but hey, it’s early.

Friends in the Palestinian solidarity movement have a term “PEP” meaning “progressive except for Palestine,” which I have mentioned could also be applied to those who are “progressive except for psychiatry”; maybe we’ll see the two PEP groupings “intersect” here by the time we’re done.

Report comment

OH, as you have probably already learned through your experience with psychiatry, what most of the world believes does not make something true. Do you prefer the rule of Hamas, Hezbollah, and ISIS? And Richard, ancient Greece was composed of many types of governments.

Report comment

Hi there oldhead

Te situation in Israel is too complicated for these trite statements…

Do you know that the distance from Gaza to Tel Aviv is 50 km? (compared to 34 km from Ft Lauderdale from Miami, or 25 km from JFK to Jersey City)

Also, when I visited Beit Soteria in June last year there was some debate about whether the front door should be locked – many residents wanted it locked for their own feelings of safety, as did the Israel Dept of Health, and only one resident was objecting to this

Report comment

No one understands Israeli psychiatry as well as I do. I was involuntarily incarcerated, drugged almost to death, and left to rot in an Israeli psychiatric prison about a decade ago. The stories of those who suffered in psychiatric prisons in Israel sound all too familiar to me. It seems like just yesterday I was being thrown onto a gurney in an windowless white room, bound hand and foot, and subjected to repeated psychiatric torture.

The prison? Eitanim Hospital. http://www.psjer.org.il/?CategoryID=255 The psychiatric prison warden? Dr Katsenelson. The neurotoxic drug? Clopixol. In that dank prison cell I was once clobbered in the head and knocked to the ground by a huge Russian speaking inmate. I remember the other drugged up zombies that wandered back and forth through the dirty hallways. I escaped once, but was dragged back into the dungeon by psychiatric enforcers. After more than a month in this prison, a month of drugging, torture, and abuse, I was released, but my recovery, even after a decade, has never been complete.

Miriam’s comment resonates with me: “The pills feel like a Holocaust, and they are like Auschwitz, and they bring the world down upon us. I used to pray to God that He would help me get better without medication.” How ironic that the very country that was established as the new homeland for the Jews, the State of Israel, would become a home to such psychiatric prisons that distribute “pills that feel like a Holocaust” and “like Auschwitz.”

Loren Mosher’s Soteria house may have challenged the psychiatric paradigm to an extent, and Lichtenberg’s new project may challenge the current psychiatric paradigm in Israel in a similar way. Nevertheless, even these more humane institutions do not adequately challenge the underlying false claims of psychiatry. As long as the myth of mental illness runs rampant, including that sacred symbol of psychiatry, namely “schizophrenia,” psychiatry will continue to prosper at the expense of innocent lives.

Psychiatric prisons and even psychiatric stabilizing houses would be obsolete were it not for the pervasive myth of mental illness by which innocent people are labeled with fictitious “diseases” and drugged into oblivion. As the critical psychiatry movement gains momentum in Israel, now is a good time to invigorate the antipsychiatry movement in Israel as well. While I certainly advocate for the humane treatment of all human beings, it should be obvious by now that psychiatry is inherently and diametrically opposed to anything humane. Belmaker and others may still make “a case for selective use of antipsychotics,” but that is because neither Belmaker or most of the others who make this case have ever been on the receiving end of the euphemistically named “antipsychotics.”

In any case, this is an interesting article, and it is certainly a good thing that Mr. Whitaker’s work will be translated into Hebrew. Perhaps the Messiah will return before that time, but we shouldn’t wait until then to get the ball rolling for antipsychiatry in Israel. Yalla!

Report comment

I have read all your words with great reverence, although you have one mistake (which I know of). You wrote: “but that is because neither Belmaker nor most of the others who make this case have ever been on the receiving end of the euphemistically named ‘antipsychotics.'”

Belmaker actually tried it on himself in the early 1980s, suffered from it a great deal and even published the matter in a scientific journal. Whitaker mentioned this in the above article as a sign of Belmaker’s open mind. The problem is only with the conclusion that Belmaker came to after of this experiment: what destroys healthy people is useful and important in the case of people like us.

Report comment

“The problem is only with the conclusion that Belmaker came to after of this experiment: what destroys healthy people is useful and important in the case of people like us.” A rather counterintuitive conclusion, especially given the reality that all doctors are taught in med school that the antipsychotics / neuroleptics, all by themselves, can create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome and the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia” via antipsychotic induced anticholinergic toxidrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

But it’s apparently difficult for the psychiatrists to come to grips with the reality that love cures all wounds, as opposed to their psychiatric “hammer” (the antipsychotics), which create the very symptoms they are claimed to cure.

Glad to hear Israel is setting up Soteria Houses, best wishes for the success of such, and let’s hope and pray the US moves towards a love vs. hate paradigm as well. I do agree, the antipsychotics are “pills that feel like a Holocaust” and “like Auschwitz.”

Report comment

Yes. Thank you for your kind words. The conclusion is wrong, but even the method is wrong. I’m sure that Belmaker didn’t throw himself onto a gurney, bind himself hand and foot, and forcibly inject needles into his buttock. I highly doubt that Belmaker would be able to administer to himself doses high enough to compare with anything that happens to real life psychiatric prisoners. In any case, this is besides the point because the vast majority of people who advocate for psychotropic drugging don’t try these kinds of “experiments.” It would be folly to do so. The truly open mind will close itself on the endeavor to abolish psychiatry.

Report comment

You’re in good company, Dragon Slayer — the legendary “mental patients’ liberation” icon Howie the Harp and his partner Joyce, both now departed, had similar tales to tell about Israeli psychiatry. Looks like your own experience 30+ years later shows how things have since “progressed.”

Report comment

If you have any record of those tales, I would love to hear them. Thanks oldhead.

Report comment

That would be a hard one. Maybe search early Madness Network News issues online? If I stumble upon anything I’ll let you know.

Report comment

Thanks.

Report comment

Terrific story. Apparently the Soteria idea lives on in Israel. As the report makes clear, even with the expense of this program, it doesn’t cost as much as hospitalization. Let’s hope the Soteria idea will succeed there, and that it then may spread from Jerusalem to other places.

Report comment

Thanks Bob,

This is a very positive article.

“There’s no such thing as ‘Schizophrenia’ – its a word.”

The “Mental Health” Disability rates in developed countries are now out of control to the extent that people looking for any kind of help, are being turned away. The systems are collapsing.

My experience is that its the drugs that disable. I’d imagine any country that could produce long term alternative recovery and market it, could make a fortune.

Report comment

First of all, good shot:

https://www.madinamerica.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Womens-backyard-copy.jpg

To really understand or even begin to understand you have to experience it, and experience it for a long time… months into years. That’s the truth of the matter Robert. The gap between yourself and us is just that. I’m afraid to say it can be a gap of utter horror in the absolute extreme, so I do not advise experiencing it. Even though many or us are now almost normal, back to how we were save the bodily destruction done by the drugs, we are very affected, still have a MH medical record that harms us, the ever possibility of us being sectioned and drugged up again, watched for any sign of behaviour that qualifies us as a danger, our medical records accessible to verify a past diagnosis. (so it must be true) This hangs on us. Psychiatry enabled Nazism to mass murder, the same mentality still exists, this is clear, the brutality is still there and a human rights crime. Sure be critical of a crime but it’s got to be realised and then prosecuted and justice given. Psychiatry must end, and actually helping people who are suffering in what ever way begin. The question of being non-judgmental can only ever be ostensible, humans judge inherently, we have to, but we can show a surface of being non-judgmental, this would be a good start.

Report comment

Thank you for your article, Mr Whitaker.

In France, the psychiatric hospital day costs between 500 and 1,000 € per day per person (between $ 600 and $ 1200), that is to say between 15,000 and 30,000 euros per month (between $ 18,000 and $ 37,000)

It is much more expensive than in Israel. The question is: how is it possible to achieve such high costs?

Here is my answer:

The psychiatric hospital functions like any institution in a bureaucratic society: its ultimate goal is to grow indefinitely. When a day of hospitalization costs 100 € per person, it is simply a stage in its development; later, it will cost 200, then 500 and 1000 euros, without upper limit. It is only the competition between the institutions, and the limits of the state budget that governs the growth of expenditures, I would say the waste of the state.

Also the argument that Soteria houses are “cheaper” than the psychiatric hospital is fundamentally irrelevant. The civil servants defend the reduction of the budget of the institutions only if:

1) The state budget is decreasing globally, and then it is necessary to make budget cuts (and yet institutions like to borrow more than reason)

2) the money saved somewhere can be reinjected elsewhere (this is what happened when they closed the psychiatric hospitals to reinject the money into drugs of the pharmaceutical industry).

I do not think that moral principles will move psychiatry; I would even say it’s a baroque idea.

Basically, we must be aware that we live in a bureaucratic and competitive society, with institutions that want to grow indefinitely under the principles of “state capitalism”.

Report comment

It is hardly ‘irrelevant’ to point to the fact that Soteria houses are less expensive than state hospitals. The biggest difference is that state hospitals are literally prisons, and Soteria houses aren’t prisons, so why pay so much for a prison, and a prison that houses people who have broken no laws.

I fully concur when it comes to some of the things you are saying about the business aspects of psychiatry, and the circulation of money. Establish any kind of institution, and then, because of the business bureaucratic end of it, they become almost impossible to eradicate. After all, this institution or that puts bacon on the table of a number of households.

I think. however, that moral principals have to kick in at some point, that is, you don’t have to aid and abet these murderers (i.e. psychiatry in collusion with big pHarma and the government) when you can oppose them.

Report comment

$ 5500 a month is still ridiculously expensive, and the men’s soteria house has its door locked. Whitaker also points out that these houses are run by repentants of biological psychiatry. There are valid reasons for being extremely circumspect.

In my case, my income was 470 € per month (US $ 580), and now I have no income, I live on my savings. I have a problem with the fact they are spending so much money on the pretext that they are psychotic, whereas Soteria homes are supposed to be communities with extremely low fees.

What I say is irrelevant? I sincerely ask the question. In France, I see officials who earn more than 8,000 € ($ 9,700) a month to drug their patients to death, and who always demand more money and staff under their control. It is the psychiatric dictatorship, with associated privileges. Meanwhile, I have a psychotic at home, who pays 200 € rent (250 $) and 240 € for food and services (290 $).

In addition to the “therapeutic” aspect – which I think is a fiction, a stupidity – I see the economic aspect, with people who earn money with the psychosis of others, and psychotics who earn ” disabled allowances “. As far as I am concerned, I have supported and I support many psychotics, and I have not earned anything as money.

From my point of view, psychiatry is a huge swindle, the legalized mafia. Both psychiatrists and psychotics are crooks. Families are opportunists. It is a huge machine to brew money, sell drugs, marginalize the “abnormal” people and indulge in a career of sick.

Because being psychotic is a profession. It’s a shitty profession, it’s not much paid, but a profession anyway. It’s part of the division of labor. You are crazy, I am a psychiatrist, and together we trade drugs, psychiatric prisons and pump a maximum of wealth from society. For you, 810 € per month ($ 990), for me, 8000 € (9700 $).

The real background of Soteria is the absence of psychiatry, the absence of psychotherapy: you put people in community, and they manage. If people do not reject each other anymore, where is the madness? There is no more psychotherapy, and there is no more madness either. You adapt society to what people are, you do not try to adapt people to society. So people stop going crazy.

Report comment

This kind of over priced private facility, as well as the locked door, are problematic. I agree with much of what you say, however, I think the Soteria project is a good one that could work under the right circumstances. The “therapeutic” aspect may be baloney, however, the living arrangements aren’t baloney.

I’m not saying psychiatry isn’t a huge swindle. I’m saying that any living arrangements outside of psychiatric imprisonment, what you get with the state hospital system, is a big improvement. Psychiatric imprisonment isn’t only a big swindle, it’s constitutionally unsound as well, but as long as it’s the law, some people will need a way around it. Other types of ‘safe houses’ are a good idea, too, but, in some cases, without the sort of history that you have with Soteria houses, perhaps even more difficult to set up.

Report comment

Pesach told me when I visited that no one is turned away due to lack of funds

Report comment

Sylvian, are there any Soteria or subacute crisis stabilization models in France, such as crisis hostels or residential crisis programs that offer psychiatric treatment in a homelike environment?

Report comment

Bob

Great investigative journalism that reveals some very important kernels of change (of worldwide significance) emerging within the Israeli “mental health” system.

I would like to raise 3 questions/concerns regarding some of the particular details revealed in this blog. I raise these to promote further discussion and debate regarding some contentious issues involved in trying create a paradigm shift in the world. These are NOT criticisms meant to undermine the overall importance of this great blog.

1) Bob you said: “If this initiative succeeds Soteria homes will become a centerpiece of Israeli psychiatry.”

I think this statement tends to overestimate what this experiment is doing within the Israeli “mental health” system. Even though there are clearly some more open minded visionaries working in this system willing to experiment, they are up against some powerful forces in the pharmaceutical industry and the APA. All it will take is a few serious setbacks for THE System to discredit these alternative programs (and its leaders) and to reinforce the value of hospital incarceration and drugging as a quick and easier form of social control.

We cannot forget that we here in the U.S., and those citizens in Israel, live in despotic/pseudo-democratic regimes built upon a foundation of profound forms of imperialistic oppression. Changes of the magnitude required to fundamentally end all forms of psychiatric oppression, ultimately run up against an inherent need by current governments and institutions to maintain maximum control of any forms of social unrest. This statement is NOT meant to undercut these developments but only present a more sobering approach as to what may be required to actually achieve this paradigm shift.

2) Pesach Lichenberg is quoted in his description of the Soteria experiment by saying “…What could be done, he wondered, to exploit the placebo to its maximum? Couldn’t a different setting help achieve that?”

It must be pointed out here that the Soteria environment is NOT an example of the “Placebo Effect.” Everything described about this radically new environment for recovery, is the exact antithesis of what can be expected from a psychiatric hospital experience, including with the massive amount of psychiatric drugging. In fact, it is vitally necessary to make the point that there are huge differences in what participants in these programs will experience related to the characteristics of “respect,” “love,” “nurturance,” “boundaries,” “safety, and especially, the absence of no (or very little) psychiatric drugging.

3) And finally, Bob, I need to continue an important contentious dialogue regarding the use of the language describing psychiatric drugs as “medications.” While this might seem like nit-picking, or very trivial when looking at the importance of promulgating the lessons of the Soteria experience, I strongly believe it is necessary to once again raise this issue.

In this article, both you and others go back and forth using the terms “psychiatric drugs” and “medications” interchangeably. When “psychiatric drugs” is used it is very clear what the meaning is and does not somehow make your comments sound like an “outlier.” In fact, I often read hardcore biological psychiatrists use the term “psychiatric drugs” when describing their prescriptions as the centerpiece of their so-called “treatment” modality.

However, when you and others slip back into referring to these drugs as “medications,” it is reinforcing one of the centerpieces of the entire Medical Model of so-called “treatment.” Bob, everyone of your books has exposed the myth of these drugs being some form of “magic bullet medication” targeting “diseases” or “chemical imbalances” in the brain. Your books, along with those of Peter Breggin and other critics of Biological Psychiatry, have exposed the fact that Big Pharma and other Medical Model proponents, have literally spent several billion of dollars on highly crafted PR campaigns convincing the worldwide public that their mind altering drugs are “medications.”

Bob, wouldn’t it be a good thing, if every so often someone said to you (and others, avoiding the “medication” term), “Hey, I noticed that you seem to always use the term “psychiatric drugs” and avoid saying “medication,” why is that?”

Wouldn’t this be a great opportunity to explain the huge difference in this terminology, and why you choose not to want to reinforce, or somehow support, the dangerous myths promoted by the Medical Model. By doing this you WILL NOT in any way be undermining your credibility (or scientific credentials) by somehow avoiding the term “medication,” but you will only be maintaining a clear consistency of a well thought out scientific and political narrative.

We cannot underestimate the overall importance of making specific language changes (from “medication” to “psychiatric drugs”) in our efforts to seek a paradigm change on a world scale. Any serious examination of prior significant historic movements, would validate the importance of changing language as part of these historic shifts. Let’s start the consistency of this language change NOW!

Great work, Bob. Carry on! You inspire us all.

Richard

Report comment

Richard:

I don’t have strong political views. I can see both sides’ points. The way I view things is that all societies must be somewhat oppressive, since that’s what the essence of a society is – people giving up certain freedoms to pursue their own desires at will, in exchange for living in a safe, efficient society. Without some rules, restrictions, and demands you’ll have anarchy. We seem to have achieved an effective society without oppressing people as much as in other nations (with the obvious exception of slavery). That’s why many people have always wanted to leave their lands to come here. I think we’re most oppressed now by the medical model’s lies having become so ingrained into our culture’s psyche, that people now believe they’re much less capable/adaptive/free-willed than they really are. In effect, this causes people to oppress themselves, and then to voluntarily seek psychiatrists who oppress them more. My goal is thus to correct psychiatry’s lies so they’ll realize they do have the power/ability to choose/pursue their own paths.

Lawrence

Report comment

Lawrence

You said: “I don’t have strong political views. I can see both sides’ points.”

We live in a world where it is becoming more and more difficult for people to straddle fences. Especially when those fences are becoming as sharp as razor blades. Fence sitting can soon become a dangerous and bloody mess in these kind of times. Just ask those Germans who stood aloof and hesitated in the 1930’s. AND what do you currently see (or want to unite with) on Trump’s side of the fence, or rather, wall?

Political indecision, political “neutrality,” and/or intellectual laziness in these times, is to abandon any kind of moral compass and eventually morph into becoming part of THE problem.

You said : “We seem to have achieved this without oppressing people as much as in other nations (with the obvious exception of slavery). That’s why so many people have always wanted to leave their lands to come here.”

This statement contains a great deal of American chauvinism and/or ignorance. The U.S. is an Imperialist empire whose high standard of living has been accumulated over the last century on the backs of many Third World countries.

U.S based atrocities did not somehow end with the Civil War. What about the 2-3 million Asian people who died because of the U.S. led Vietnam war of plunder? What about the 500 thousand to one million Iraqi people who died from the largest “drive by shooting” on the planet earth?