I first corresponded with Zel Dolinsky five or six years ago, and after that we would exchange emails every few months. In this correspondence, I knew him as a scientist who had read my book Anatomy of an Epidemic, and someone who was now doing his own review of source materials and the themes I had written about.

Although I could sense that he might have had his own personal reasons for questioning the merits of psychiatric drugs, I saw him through the lens of his professional career. I knew he had a PhD in psychobiology and had taught at a medical school, but it was only in the last two weeks that I learned the full extent of his career. He had taught at UCONN Health Center in Farmington for nearly ten years, and he had worked as a “supervisory scientist” for pharmaceutical companies for 13 years. Much of this pharmaceutical work came when he was “director of medical writing for a major CRO.” (A CRO is a contract research organization that conducts clinical studies of new drugs for drug companies.)

As Zel did his own research into the long-term effects of psychiatric drugs and their myriad array of side effects, he became increasingly distressed. In his professional career he’d helped promote beliefs, packaged as scientific truths, that he had now come to see as false. His emails revealed both a sense of bewilderment and a sense of loss. How could he have spent so much of his adult life in a pursuit—related to his research, teaching, and working for pharmaceutical companies—that he now saw as doing harm?

But throughout those years, he always wrote from the perspective of a scientist.

About five weeks ago, he stepped forward with a generous donation in response to our fundraiser. I thanked him, and in his reply, he confided that he wished that our continuing education efforts had a class specifically on withdrawing from polypharmacy. It was only then that I began to understand that he was suffering from this very problem.

After that inquiry, I received almost daily emails from him, and gradually he revealed more and more about his personal struggles with psychiatric drugs. He also seemed to be on a new mission to raise this discussion with others. He’d cc me on emails that he was sending to leaders at NAMI and others involved in the promotion of their use, and often these emails contained a link to one of our articles that had told of adverse effects with psychiatric drugs. One such article he sent out was our MIA Report, “Screening + Psychiatric Drugs = Increase in Veteran Suicides.”

Then, about three weeks ago, he became obsessed with wanting to know what had happened to a young man who—according to a blog published in 2013 by Pete Earley—had thrown away his antipsychotics and gone missing after listening to me speak at a national NAMI conference. The blog was authored by the “anonymous” mother of this son, who wrote that I “had blood on [my] hands.”

I wasn’t sure why Zel suddenly had become interested in this story. At first, I thought it was his way of honoring the scientific part of his mind. He had long since come to believe that Anatomy of an Epidemic accurately reported on scientific findings, but still, what did the defenders of antipsychotics maintain? That people diagnosed with schizophrenia needed to be on these drugs, and that to speak about research that questioned that belief, which I had done, was to expose people to harm.

Zel had often written to ask if I could answer this or that criticism of something I had written, and his sudden focus on this article, I thought, could have been yet one more instance of his challenging me in this way.

I told him what I had long thought, but had never publicly stated. I told him that I didn’t believe that there had ever been such a young man. The author of the blog was “anonymous,” and more to the point, the author had told of how her son had recounted his story of recovery on drugs at a NAMI meeting, and everyone had come up and hugged him afterwards. If that were so, and this mother was now irate with NAMI for having invited me to speak, then it seemed that this person surely would be known to NAMI. Yet when I asked the NAMI president who had invited me to speak about this, she said there had been no such complaint. They had no idea who this woman was. And when I asked Earley about the letter, he acknowledged that he hadn’t tried to verify if it was authentic. And so I had come to think that it was likely a planted article, one that was designed to discredit me, and without going into the details now, there was plenty of that going on at that time.

I hadn’t thought about this for years, but Zel was newly obsessed with this story, and he lightly admonished me for thinking that it might not be true. No one could fake such a heartfelt letter.

He then set out on his own quest to find out about the young man, writing the president of NAMI, Angela Kimball, and other NAMI leaders to ask if they knew what had happened to the young man, or if they even knew who he was. Once again, NAMI didn’t have any information and Kimball referred him to Earley’s blogs. All NAMI knew was that Earley, after the first “blood on his hands” post, had written that the young man had turned up at a homeless shelter, and so at least he had been found.

Zel then wrote Earley asking for information about how he could contact the young man, and he promised that he would keep me informed as he sought to find out the “truth” of the matter. I was newly curious. Although I never fully understood why Zel had become obsessed with this question, I came to think that he might have wanted to find hope in this story, that perhaps the young man was actually doing well.

Then, on December 17, he wrote to tell me that this “might be the last time” I heard from him. It was in this email, which stunned me, that he first told me of his struggles on psychiatric medication. He wrote:

I have learned a lot from you, your books, especially Anatomy of an Epidemic, the MIA website, and the education series it offers. This learning has been painful because it contradicts all I was told about psychiatry, psychiatric medications, and our mental “health” system, and it has been painful not only because I taught incorrect information about all these subjects to medical students for nearly 10 years [but also because of his personal experience].

As I said, I am sorry that MIA does not offer a course in tapering from multiple medications because that is what I tried to do.

I am suffering from severe akathisia (which is why I am writing this to you at ~2 AM Eastern time . . . because I can’t sleep) and it has been going on for several years now despite trying to taper from Klonopin in many ways, including being “escorted” to a detox facility in Florida.

What made it difficult to taper from Klonopin is that I was also taking long term prescribed Parnate and perphenazine. I guess I was an early proponent of tapering from psychiatric drugs, though an unsuccessful one.

I donated money to MIA because I don’t want ANYONE to have to suffer the way I have and am currently doing.

I say in the subject line “This may be my last email to you” because I don’t know how much longer I can go on like this based on the akathisia and the traumas (that I have flashbacks to) that I experienced from multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. I participated in Michael Simonson’s MIA survey.

In closing, I hope to be able to forward to you the email from [Pete] Earley, but I may not be able to, depending on when/if I get his email and based on the reasons that I have confided to you above.

Finally, for some of us (probably more than we know), the choice of “Death With Dignity” is not just a catchy phrase, and after suffering for so long (which many people can’t see), it needs to be legalized in the US, because, after all we are US citizens, who have a right and should be respected in choosing how we live AND how we die (peacefully I hope) . . . something I am looking into.

I trust you concur.

This email told of personal suffering I had only glimpsed before. We exchanged some more emails, and I of course sought to find words that both acknowledged his suffering and yet offered hope that his withdrawal agonies could end. I also told him that he should consider writing a story for MIA precisely because—as he said—he had experience both as a professional who had promoted psychiatric drugs and as a user of those drugs.

Over the next couple of days, he told me that he couldn’t write his story for MIA because whenever he had tried to talk about how he had suffered on the drugs, no one wanted to believe him. At last, he cc’d me on an email he sent to NAMI’s president, and in it he told a story that he wanted to be made known.

He wrote, in part:

At the CRO and in the pharmaceutical companies, I saw many well-meaning workers, but I also saw the leaders of the CRO and pharmaceutical company executives who were driven by ego, greed, and contempt for scientific input.

This resulted in inadequately designed clinical trials, a rush to complete clinical trials at the cost of patients’ safety as well as ignoring the efficacy of drugs being developed. All for profit . . .

I am a unique individual because I have seen “both sides of the picture” as a professional researcher, academic Assistant Professor, scientific director of medical writing, quality control expert, “business person” and a “survivor of an emotional disorder.”

I am also a “survivor of NAMI”, because . . . NAMI was/is a great proponent of psychiatric medications, which I saw and heard as NAMI members talked incessantly about their medications at the many NAMI support meetings I attended. At those meetings I also heard many many lectures by professionals, invited by NAMI, talking about the efficacy and safety of psychiatric medications.

In the remainder of his email, he questioned why NAMI had accepted money from pharmaceutical companies, and why it didn’t do more to promote successful therapies like Open Dialogue that didn’t rely on drugs so much. He closed with the very question that, for some reason or another, had become fixed in his mind these last weeks: “Do we know what ever really happened to the young man who left Robert Whitaker’s 2013 NAMI presentation?”

In private, he confided that he now thought I was right. There probably had never been a young man. And that seemed to lead him to an even greater despair, but for reasons that weren’t clear to me.

On Christmas eve, he addressed a long email “to some good friends and also acquaintances.” He said it had taken him 4.5 years to write, and he gave permission to all who received it “to share it” with anyone they liked. This was, in many ways, the personal story that he had long wanted to tell but had never felt free to do so.

“I am sending it because I don’t want what happened to me to happen to others, especially children and young boys,” he explained.

In the letter, he told of how he’d had a difficult childhood and suffered many traumas, including sexual assault. He told of how this led to his being diagnosed with schizophrenia at a young age, and how this was a diagnosis that ruined his life. No one, he wrote:

“ever asked about or even seemed interested how I really felt as an ‘authentic’ young boy and young man diagnosed with Schizophrenia. . . . (no one) ever asked about how I felt about being fed a plethora of psychiatric meds as a young man or what side effects (like dry mouth or muscle spasms at work due to Haldol) that I might have had. . . . how do you think I feel/felt given that dismal/stigmatizing diagnosis very early on in my life and given all available meds including antipsychotics for it? I actually decided I would never have children because I didn’t want to pass on that supposed highly genetic disorder to my children.”

All people ever wanted to focus on, he said, was “my symptoms, especially when I was/am suffering.”

He was haunted by this beginning to his adult life. He was hospitalized eight times, which he remembered as traumatic; he was put on more drugs than he could remember; and he eventually attempted suicide.

And yet, he did rise above all this, at least for a time. He earned a PhD, did medical research, and taught at a medical school. He then gave that life up to train as a massage therapist, working for three years in that capacity at Hartford Hospital. Following this career change, he noted proudly, he had worked as a “Warmline operator for over a year supporting people on the phone who needed emotional support.”

At some point, he had become disabled, most likely from the effects of the drugs. He was now 67 years old and residing in an assisted-living facility, and he had given up all hope that he would ever be able to get completely free of the medications. He closed his Christmas Eve email with this message: “The greatest human freedom is to live and die according to our own desires and beliefs.”

On Christmas morning, he sent a final email to me and others. He thanked those who had shown their concern and shown that they cared for him, but his mind was made up. He would fulfill his plan of dying with dignity, and he once again said that he hoped his last words might be made public in some fashion.

He wrote:

First, I am of sound mind, understanding, and I am not hallucinating and not delusional. Please don’t condemn me or feel sorry for me.

I regret that I have given up. But as a friend once said to me, “Don’t feel like you have given up . . . You haven’t given up, the world has given up on you. You’ve done the best you could to stay healthy!”

So that the pathologist or medical examiner/physician does not have to perform an autopsy, mine is not a “suspicious” death. I alone have chosen to end my own life with dignity.

While my close friends support my philosophy and decision, difficult as it is for them and me, none of them know that I have done this or the method I have chosen, nor has anyone assisted me in performing my choice.

I do not take this decision lightly and have thought about and planned it for many years. I realize that at times life is precious.

I am writing this note in hopes that “death with dignity” is understood, supported and legalized in the US and abroad for those who don’t choose it on the “spur of the moment,” and that it is not so difficult to do and that it must be done “in the shadows.”

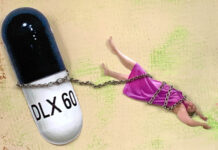

I have not slept in many years, let alone been able to rest, due to extreme symptoms of akathisia . . . I also can barely walk, due to not sleeping and incessantly pacing . . . thanks in large part to (a psychiatrist) who prescribed Klonopin (clonazapam) to me in an uneducated fashion for ~25 years while also being unfamiliar with the literature about it.

I didn’t want to die but based on how I feel physically . . . I can’t live.

Within an hour or so of writing that last email, he “died with dignity.” His sister sent out an email Christmas afternoon telling those of us who had received his last email that he had passed that morning and that she was now seeking to locate the person he had asked to take care of his beloved cat, Euphrates.

Such is the “personal story” that Zel Dolinsky told in his last weeks. The man whom I knew as a scientist revealed how a diagnosis given to him when he was a teenager—and the subsequent drug treatment—had so harmed his inner sense of self and his physical self, too. At the end of his last letter, he wrote: “I try my best to tell the truth.”

My heartfelt condolences to everyone who knew Zel. Robert Whitaker, I can not put in words the gratitude I have for you and your work. Your work lead me to find my way out of psychiatry hell. I want to tell you, you and everyone on MIA and other organizations are reaching us. I am doing better now and I have shared my story of psychiatric drug damage with a 21 year old on a warm line and she has successfully come off Klonopin. Not bc I have. But bc she learned to educate herself so she has been allowed the medical legal duty of informed consent. So I thank you and beg you to keep up this life saving work. I can attest to the pain one is in to want to take your own life. And how or why this is the current “help” for teenagers in distress is to state it kindly bewildering. Horrifically sad but may Zel find peace out of this world bc obtaining peace here is just way too difficult.

Report comment

Had we known earlier we might have been able to help him. Tardive Akathisia.. utterly horrific in the absolute extreme. Important post… I will reference this into the furture of Evolutionary Psychiatry.

Report comment

I know, my first thought was: did he know about Surviving Antidepressants? We’ve dealt with a good deal of polypharmacy. There are things about his situation that might have made that challenging, however. In an institution, it is harder to taper and reduce doses. We haven’t done much with the MAOI’s, which are horrific drugs to deal with.

RIP Zel, I’m glad you got the dignity. I think about that diginity almost daily in my own life.

Report comment

Thank you, Bob, for letting us know about Zel’s (Helpstillneeded) passing and for respecting his framing of death with dignity. He and I were certainly on the same page on this topic. The dignity part seems very hard for many to grasp still, but all it ultimately means is having supreme agency over one’s own passing as a final act. It’s a choice I fully intend to make for myself when the time comes.

I have appreciated his comments over the years and will be sad not to see any more of his postings. He understood the anger and despair felt by those of us whose lives have been robbed and bodies destroyed by a forceful, coercive, and deeply harmful therapeutic state.

Report comment

Thanks for connecting the MiA name with the real name, kindredspirit. I, too, “have appreciated his comments over the years and will be sad not to see any more of his postings.”

Report comment

Thanks kindredspirit for the name.

I agree with you.

Report comment

And why not ask by law with of destroyers of bodies and lives? After all, those “doctors” committed serious crimes. Why should they go unpunished?

Report comment

And why not ask by law with of destroyers of bodies and lives? After all, those “doctors” committed serious crimes. Why should they go unpunished?

Report comment

Thank you for sharing Zel’s story, Robert. Rest in peace, Zel. Akathesia is a horrific effect of the neuroleptic drugs, often denied as a common effect of that drug class, by the psychiatrists.

And absolutely, defaming child abuse survivors with the “invalid” DSM disorders, then neurotoxic poisoning them, is stigmatizing, and the antithesis of helpful. But such child abuse covering up crimes are a systemic “mental health” industry problem, and these crimes are by DSM design.

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

Caring for survivors of abuse and trauma should be taken out of the hands of the “mental health” workers, since they’ve been systemically betraying child abuse survivors, on a massive societal scale, for over a century.

My condolences to Zel’s loved ones. And I’m grateful Zel told the truth.

Report comment

Psychologist Dr Jordan Peterson

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jordan_Peterson

“….In 2019, Peterson entered a rehabilitation facility after experiencing symptoms of physical withdrawal when he stopped taking clonazepam, an anti-anxiety drug. He had begun taking the drug upon his doctors recommendation following his wife’s cancer diagnosis.[144][14….”

Report comment

His passing shows the limits of conventional formal education in pharmacology. He suffered for years from dyskinesia/akathisia without realizing that manganese is therapeutic for it, if we can believe Richard Kunin, MD, who treated a small series of patients with it in the 1980’s. Maybe that’s because the orthomolecular guys took it up right away and now routinely use it, proof positive to the orthodox that such treatments are useless.

Report comment

Manganese doesn’t work for benzo wd. Been there done that along with thousands of others in the “benzobuddies” forum. That is the biggest problem; nothing helps recover your depleted gabaA except time. Nothing.Only lots and lots of time.

Report comment

I’m entranced by the O=H N=O=O=H theory of benzo damage. Ramcon over at BB has been exploring various mechanisms with the goal of ‘cure’. I’m not holding my breath, but the above theory explains perfectly the ‘waves and windows’ pattern of symptoms.

I’m about to start my 6th year post Klonopinm, inspired by Anatomy. It is a nasty nasty drug. I, too, want a ‘death with dignity’ option–not sure how I’m going to obtain the chemical agents necessary–guns are out. I don’t want to cause further trauma upon the discovery of my corpse. I keep asking the minders for that BLACK PILL they so obviously want to administer.

So sorry to read about yet another victim of psychiatry. I think there *is* momentum, but the forces against honest inquiry are vast.

Report comment

No. It’s use is more or less confined to antipsychotics, which antagonize manganese. I don’t know what the story is on SSRI’s, which seem to induce certain neurological properties that resemble dyskinesias brought on by antipsychotics.

Report comment

I would be interested in seeing if niacinamide has any value in withdrawing from benzos, occupying the same receptor sites that benzos do. I know it doesn’t work for alcohol withdrawal (but niacin does), but theory suggests it might for benzos.

Report comment

Already have told you, charris that we have SENSITIVITES to supplements…b vitamins in particular.

If I take a b or eat too many green leafy…I will not sleep for days.

Report comment

Thanks for sharing, Bob.

Every time I read one of these heartbreaking stories, it makes me so glad my family and I side stepped all the pain and misery caused by the mental health system and its drugs despite our path not being an easy one. Maybe some day we’ll find a mutually amenable way that I can share how we did it here on MIA.

But I can certainly empathize with Zel: I have struggled with similar thoughts for decades though for completely different reasons. It really is too bad that so many people in this world are too blind and self-absorbed to see those who are suffering alone, and how it strengthens both people when they learn to ‘attach’ to each other.

Sam

Report comment

Thank you Robert.

I have tears of course, because it hits so close to home.

We grieve what might or could have been.

And in all things, we have to live in shadows, hide from the

people who refuse to acknowledge one’s truth. Because truth becomes “illness”, and that is a huge onslaught on the human.

It is a horrible path sometimes for those sensitive souls, to

be given labels, like a chunk of meat.

To carry around such pain, which can only be released by those or

the system that caused it. Although it is often too late.

And seeking affirmation in the forms of therapy, well the brain knows it

is trying to seek peace from the sources. And there is not much they can do for the after effects of spiritual and physical harm.

Life is sweet, but can come with a lot of pain.

I realize proponents of all things psychology or psychiatry, religions will think it was a “mindset” “depression” that took him away.

They can “think” what they will, because “thinking” does not make it so.

I am glad he was successful but it is a crying shame he had to be by himself. There are many topics, that we have to pretend do not exist.

My condolences to his family and to Robert and MIA and to whoever will miss him.

Report comment

Bob and All

Thanks for sharing such a deeply personal story (from both Zel Dolinsky and you, Bob), and I want to express my condolences to all who knew this very courageous man.

This story, in so many ways, concentrates EVERYTHING that MIA and “Anatomy of an Epidemic” has been about for the past 8 years.

We (those who live in the U.S.) must constantly remind ourselves that we live in a trauma based society, and the Medical Model does everything to steer us away from understanding the connection between psychological pain and the surrounding environment.

We have a long road ahead; psychiatry and the entire Medical Model are so deeply embedded in every pore of this very sick society. Truly Revolutionary type change is necessary to move the world in an entirely different direction.

Thanks to the Zel Zelinsky’s and Bob Whitaker’s of the world who dare to speak the truth.

We love you Bob – Carry on!

Richard

Report comment

“We love you Bob – Carry on!”

I agree Richard! I have so much respect and gratitude for Robert Whitaker and the courage and integrity he has to have embarked on such a daunting but profoundly needed mission.

I also honor those who bravely share their personal stories in the hope of helping others.

Report comment

“We live in a trauma based society, and the Medical Model does everything to steer us away from understanding the connection between psychological pain and the surrounding environment.” Well said.

Report comment

Thank you so much for sharing Zel’s story. I can relate to the feeling of wanting the real truth of your life to be told and heard. I appreciate all you do Mr. Whitaker. Thank you for being a voice for the “voiceless”.

Report comment

And if you read back through his comments, you’ll see he had no respect for authority granted to him or others by title or position. He earned my respect for that alone.

Report comment

Big Pharma is absolutely sickening. I myself am currently in my 5th year of suffering from klonopin/ativan withdrawal. There is a website called “benzobuddies”……..go there for all the proof you need of the suffering caused by benzos and antidepressants. These pharmaceutical companies AND Drs. need to have a big ole class action law suit against them to hit their pocketbooks in the billions of dollars. I am afraid money is the only thing that will force them to admit the dangers of getting off and even staying on these drugs because you gain an immediate tolerance to benzos. I had evil looking hallucinations every night accompanied by abject terror for 3 full years and couldn’t even think about sleep unless the sun was shining. It was sheer unmitigated terror. I had daily blood pressure spikes over 200. Daily! I believe I am 80% healed and am so grateful but I will never forgive the big pharm companies nor Drs. who claim these drugs are “easy” to abstain and kick. Again…..go to “benzobuddies” and see just how “easy” it really is. (Not!) The only reason I haven’t committed suicide myself…..long ago…..is because of my belief

system. I am so sorry for your loss Robert and hope your friends experience assists in forcing the medical community to stop lying about the dangers of these drugs.

Report comment

My beliefs kept me from suicide too, Rconrad. Hugs!

Sadly Zel’s reason for ending his life was the damage inflicted on him by psychiatry.

Report comment

“These pharmaceutical companies AND Drs. need to have a big ole class action law suit against them to hit their pocketbooks in the billions of dollars.” I agree.

Someone find a lawyer who’ll take the case. I’ve still yet to find one. Back when a malpractice suit was legally appropriate for me, it didn’t happen, since two years is the statute of limitations on malpractice. But it took me three years, as one who got in the top 99.95% of my math SATs, to learn “medicaleze,” and find the medical proof of what all the doctors are taught in med school. Which is that the antipsychotics and antidepressants can create psychosis, via anticholinergic toxidrome. A reality the doctors can’t deny.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

I recently contacted some lawyers about a class action lawsuit, based upon Whitaker’s findings. Because many of us here were turned into “bipolar” misdiagnosed people, due to having the common adverse effects of the antidepressants misdiagnosed as “bipolar,” which was blatant malpractice, according to the DSM-IV-TR.

“Note: Manic-like episodes that are clearly caused by somatic antidepressant treatment (e.g., medication, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy) should not count toward a diagnosis of Bipolar I Disorder.”

I was told recently by the law firms I contacted, “we don’t deal with psychiatric malpractice.” So who does? Crickets.

I agree, we do need a class action lawsuit against the medical and pharmaceutical industries, who have been colluding against their clients, to harm them for millions in profit, for decades. After promising to “first and foremost, do no harm,” of course. Can you say hypocrites?

But where are the lawyers? Oh, they do seem to be willing to represent those Epstein and Weinstein rapists, while our country’s, primarily child abuse and rape covering up, scientific fraud based “mental health” professionals’ goal is actually covering up child abuse and rape on a massive societal scale. But the lawyers are not willing to represent the parents or survivors of sexual assault, against the systemic, primarily child abuse and rape covering up, “mental health” profiteers.

But our society’s, scientific fraud based, psychological and psychiatric “mental health” workers do need to get out of the illegal, child abuse and rape covering up business. Since their systemic, child abuse and rape covering up business – which also functions as a pedophile and child sex trafficker empowerment business – is destroying Western civilization, even according to world leaders today.

https://www.amazon.com/Pedophilia-Empire-Chapter-Introduction-Disorder-ebook/dp/B0773QHGPT

https://community.healthimpactnews.com/topic/4576/america-1-in-child-sex-trafficking-and-pedophilia-cps-and-foster-care-are-the-pipelines

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/us/backpage-sex-trafficking.html

https://worldtruth.tv/putin-the-west-is-controlled-by-satanic-pedophiles/

As the mother of a child abuse survivor, who was attacked by child rape profiteering and covering up psychologists and psychiatrists, I was “lacking insight?” Maybe initially, but not once the medical evidence of the abuse of my child was handed over.

And in reality, it is the child rape covering up “mental health” workers I dealt with, who are still today lacking foresight, and an understanding that they need to get out of their illegal child rape covering up business. And sadly, this includes the head bishop of my childhood religion, who runs the Lutheran Social Services organization.

Report comment

Here is the main problem with lawsuits: Doctors were following “Standard of Care” and as long as they follow “Standard of Care,” they are not liable for negligence, malpractice, or any other criminal action.

THe HARD PART is getting lawyers / lawsuit to address that the “Standard of Care” is wrong. Usually the only way to prove that is is through FDA, which is now wholly an arm of pharmaceutical interests. Like Vioxx. That wouldn’t happen now.

MORE PEOPLE DIE from these drugs, their effects, and withdrawal from them, than die in “opioid” events, or “vaping accidents” – and yet, all the outrage is there. Additionally, if you look into the opioid events, there is in a huge percentage of them (80%? 90%) a psych drug component, whether a benzo or a seizure drug like pregabalin (which is widely abused in the UK) or gabapentin.

Report comment

Go to “benzobuddies.com” and you will find all the facts you need from the tens of thousands of suffering forum members. Me included.

Report comment

Have benzobuddies lobbied the government? Or has anyone tried?

It seems the government won’t help. How about protesting at legislative buildings?

Or on the streets?

The word has to get out to unsuspecting victims.

Report comment

hey Sam, I’ve been appreciating your comments.

However, “appeal to authorities” is going to achieve nil result. “Lobbying” against the $,$$$,$$$ that pharma has to offer is like trying to stop the ocean rising with popsicle sticks.

As I see it, the best way to approach this is word of mouth. Being a light of recovery that shines so that other people can see it. “How did you do it?”

We each need to rebel within, because – lobbying the government is not going to heal someone from these drugs. It requires radical responsibility – for your moods and behaviours, and your own dosing schedule for tapering.

Whether that tapering advice comes from BB or SA – or just from your own work with Will Hall’s Icarus Project “Harm Reduction Guide.” (how I started, then I went to SA for moral and social support) – doesn’t matter. But we need to get the word out: DOCTOR TAPERING SCHEDULES ARE UNSAFE.

I need to review my “dear doctor” letter and put it somewhere like “Googledocs” so that others can use it. I don’t use Googledocs, so perhaps someone who has an account can help me with that.

Because Doctors need education, too. They need to know that there is another way. It’s hard to present to doctors, because their education was expensive and tedious, and it’s hard for them to accept that what the drug companies have taught them about the drugs might be wrong.

It would help to have DOCTORS teaching DOCTORS about harm reduction protocols for reducing psych drugs.

I have a friend whose Tardive Dyskinesia is getting out of hand (they have had this condition for over 20 years) and what does her p-doc do? Cuts the neuroleptic by 25% right up. And they lose sleep and struggle with intrusions while waiting for the neurotransmitters to adjust…

We can’t just go around smacking GP’s and p-docs (like I would like to) – but if we can distribute educational materials that are science-y enough, and short enough for a busy doctor to comprehend in short order, it might help.

I used my “Dear Doctor” letter for a friend. Her doc was going to cut in half for 2 weeks, cut in half again, and then discontinue. A typical doctor response (and recipe for disaster). I wrote my “Dear Doctor” letter, and at least the doctor reduced that to 25% per month. Slower, not without consequences, but not a disaster.

It’s so sad to have lost Zel, when there might have been another way. But he chose what he chose, and a light went out in this world.

But “lobbying” Pollys who are getting their pockets lined from pharma, is a waste of effort. I think the solutions are grass roots. Revolution doesn’t happen by lobbying politicians. It happens when the little guy decides: ENOUGH IS ENOUGH.

Report comment

Hi janCarol, thank you.

Would it be possible for you to write a “dear doctor” blog on here?

Report comment

Sounds like how Mom’s GP takes her off her “antidepressants.”

Poor Mom acts like a zombie most of the time. 16 hours of TV a day. Can only discuss pop trivia and gets irritated at anything “for eggheads.”

At 69 she takes Wellbutrin and Celexa. But doctors prescribe it so it must be good for her. (She assumes.)

Report comment

Fiddlers’ Green

Halfway down the trail to Hell,

In a shady meadow green

Are the Souls of all dead troopers camped,

Near a good old-time canteen.

And this eternal resting place

Is known as Fiddlers’ Green.

Marching past, straight through to Hell

The Infantry are seen.

Accompanied by the Engineers,

Artillery and Marines,

For none but the shades of Cavalrymen

Dismount at Fiddlers’ Green.

Though some go curving down the trail

To seek a warmer scene.

No trooper ever gets to Hell

Ere he’s emptied his canteen.

And then rides back to drink again

With friends at Fiddlers’ Green.

And so when man and horse go down

Beneath a saber keen,

Or in a roaring charge of fierce melee

You stop a bullet clean,

And the hostiles come to get your scalp,

Just empty your canteen,

Then put your pistol to your head

And go to Fiddlers’ Green.

The origin and author of Fiddlers’ Green is unkown. It was believed to have originated in the 1800’s and was composed as a song

sung by the soldiers of the 6th and 7th Cavalry. Its first known appearance in published form was in a 1923 Cavalry Journal.

Report comment

Thank you very much for writing this Bob. It is realistic.

In the developed World “Schizophrenia” is clearly caused by Psychiatric Drugs.

Report comment

This is terrible. I don’t know if we would have been able to help Zel Dolinsky, but on SurvivingAntidepressants.org we have a protocol to taper polypharmacy and routinely help people go off their drug cocktails. It’s not easy and it can take a long time, but it can be done. (FYI, an outline of the protocol is here https://www.survivingantidepressants.org/topic/2207-taking-multiple-psych-drugs-which-drug-to-taper-first/)

When grueling symptoms such as akathisia and sleeplessness have already set in, maneuvering is more limited — but we do have people who have recovered from this.

If I, a peer counselor with no formal medical background, can figure it out, a smart doctor could do it. I hope in the not-to-distant future, many will.

Sadly, although huge numbers are being overmedicated with all kinds of drugs, we’re still in the era where adverse drug reactions are considered very rare, with very little clinical training to deal with them. It is a failure in medical practice that so many patients cannot find a doctor with even a particle of understanding about drug adverse effects. They simply do not want to get entangled in this, especially when psychiatric drugs and purported “mental illness” are involved.

Even psychiatrists will shrug at adverse drug effects and mumble something about “but the drugs do so much good!” or some such irrelevancy.

This is perhaps the cut that hurts worse — feeling abandoned by medicine — left out on the ice floe, as it seems.

Report comment

Alto, it’s good to see your name up here again! I’ve missed you. Thanks for the post!

Report comment

Altostrata, I agree that there are very few Drs who are aware of/will acknowledge harm from psych drugs, and even fewer still able to ameliorate it in any way. I avoid Drs like the plague now because I’m in Cymbalta withdrawal (the last in a long line of psych drugs spanning 35 years), and based on my experience with the Drs around here, their solution would be “well, start taking it again! Why did you ever stop taking it?”

I did need to visit urgent care about a week ago for a rash. While I was there, I asked the doctor if she would check my ears. I said to her:. “I have tinnitus. I’m in Cymbalta withdrawal, and I know that can be an effect of Cymbalta withdrawal, but it can also be a sign of ear infection, and I’d like to rule out infection, so do you think you could check my ears?”

I thought I made perfect sense, but the Dr looked at me like I had two heads, said, “I don’t know anything about that,” and left the room. When she came back, she had her assistant with her.

Something I said must have really freaked her out. After that I just asked again for something for the rash and got the hell out of there.

Maybe because I spend a lot of time on this website, I start to have the – very false – belief that the knowledge of the harm of these drugs has reached the mainstream.

Report comment

Most of them don’t even know the adverse effects of the drugs they personally prescribed. I’d bet that 90% don’t even know there ARE withdrawal effects from Cymbalta. I just figure I have to educate them every time, but avoiding MDs whenever possible is much more effective. I only see them when I have no other choice or need something specific that only they can provide, like antibiotics. Don’t trust them as far as I can toss them.

Report comment

Steve,

Docs have argued with their patients for eons, not just regarding effects of meds, but illness symptoms also.

Funny how they won’t deny that an antibiotic gives you tummy cramps.

I hope my doctor never posts on here, she has pretended to be anti-psychiatry for years, yet prescribes drugs, argues or at least used to, about side effects.

She works in women’s only clinic and is proud that a “critical psychiatrist” is coming there to present.

It is amazing how many docs will pretend and be convincingly “anti-psychiatry”, yet try to please both sides.

Report comment

KateL – that rash could be exacerbated by Cymbalta withdrawal.

It seems that Effexor (in particular) invokes mass quantities of itchy skin issues – so I don’t see why Cymbalta wouldn’t have similar issues.

Yeah, I see docs as little as possible…I told one doc (a “natural medicine orthomolecular doc”) that I didn’t think that my mood was any of her business, and she said, “What a thing to say!” I said, “It’s not medical, it’s my responsibility…”

Of course, she launched into a lecture about how to improve sleep, blah blah blah, and – yep. I’d grown 2 heads again.

But until we educate them (this is helped by developing LONG TERM relationships with doctors, so that they learn you don’t have two heads, after all), they will continue “standard of care” practice as usual.

Report comment

Ah, Altostrata – I was just talking with someone who – in hospital – was prescribed drugs in DIRECT MAJOR CONFLICT with each other, and then wondered why they felt so much worse.

If doctors and pharmacists can’t handle major drug interactions, how are they going to handle tapering safely?

There is so much arrogance in the profession. Heaven forbid we should find that Peer Specialist information is more accurate, scientific, and effective than “medical advice.”

Sigh. It feels like yelling into the wind, sometimes. But thank you for all that you do in Doctor education, case study collection, and helping people off the drugs. You helped me, and for that I am eternally grateful.

Report comment

Psychiatry is an absolute crime. Crime in essence, according tasks that it is called to solve. She is the crime and from the standpoint of the current law. Psychiatry is contrary to the fundamental principles of law. Not a violation of psychiatric rules is a crime. Enforcing psychiatric rules is a crime. There is no and there can be no reason to legitimize psychiatry. This is my position, my conviction, which I ad-here to all my life. And life happened terrible. More than once I caught myself thinking that I was probably the worst victim of psychiatry. There are grounds for such an assessment. And because the I suffered so badly, I have the right to have my own judgment. My fate gives me such a right.

In 2015, I opened a petition: https://goo.gl/sMnJ6y In fact, in this petition, I basi-cally set out my claims to humanity, which permits such a monstrous atrocity, which is psychiatry. This petition suffered a sad fate. – From the very beginning, Facebook admins, and then change.org, blocked signatures. And from the very beginning, I many times paid attention to it. Wrote about it wherever he could. Despite this, without any embarrassment, the signatures continued to be blocked.

Two years later, the petition was closed. At that time, 1517 signatures were listed. At the moment, there are 1505 signatures. That is, after the petition was closed, the number of signatures was reduced by 12. How much were they re-duced during action the petition? !!!

Even then, I drew attention to the fact that neither Facebook admins nor any of-ficials needed to block signatures. This is necessary exclusively for psychiatrists. And of course, signatures were blocked according to the wishes of psychiatrists. So they have the ability to exert pressure and force the ad-min of social networks. And not only them. It looks like these criminals have tremendous power. This, their unlimited power, explains the continuation of the legitimate activities of psy-chiatry in spite of the monstrous victims and all the efforts of opponents of psy-chiatry.

Report comment

Psychiatry exists because

They set themselves up as “doctors of the mind”. People in distress go to get help.

The practice is primitive in thought, limited in thought. People that are limited in thought and deny or invalidate their patients and are one of the most closed minded people in society should not ever hold licence over the population.

Psychiatry will never succeed, in helping people. Why would anyone go into the field? Because of their narrow views and they are not employable in any other well paying jobs.

Report comment

Psychiatry will never succeed in helping people since she’s and not going to help anyone. Psychiatry has a completely different goal. She “helps” get rid of objec-tionable people. Psychiatrists, by definition, are executioners. The destruction of man they call help.

Report comment

After personally witnessing how the protections of the Mental Health Act are being ignored by the authorities in my State, I do not believe that any legislation to deal with Euthanasia could be effective, if not be down right abused.

Jim Gottstein stated in another articles comments that rights without remedies are possibly more dangerous than no rights at all (or something to that effect). Providing another loophole with regards doctors legally killing people? Really?

Of all the people I know I would have thought those who had been subjected to psychiatric ‘care’ would understand how the issue of consent is dealt with by doctors. You don’t actually have those rights when you need them most. Writing laws to give the appearance of protections could be disasterous.

And is it not the case that Mr Dolinsky has shown that it is possible to die with dignity without the involvement of money grubbing corrupt politicians who would be more concerned about the profit that could be made from the sale of Nebutal etc?

Careful what you wish for, because you just might get it.

Thou shalt not kill [except when doctor is late for tee time at the Country Club] What sort of excuses will be forthcoming for the perversion of the original doctrine? And how easily could this be ‘amended’ to be used as a weapon against certain ‘classes’ of individuals? Oh I don’t know, lets say the Mentally Ill for example?

There was a reason our newspapers (media) were told not to use the term Euthanasia because of the negative associations with the National Socialists in Germany. People might notice the Bill was simply translated from the document put to the Reichstag.

Its simply not the case that you don’t have the right to die with dignity. This might not be recognised by your government, but hey they passed laws allowing human rights abuses disguised as medicine so……

Report comment

Precisely Boans!

What’s to prevent shrinks from involuntarily euthanizing the “SMI”?

We already have no say in what they do to us. And they ignore the damage their “safe and effective” treatments have on those they regard as lab rats.

It’s only lack of insight preventing Ms. Smith from appreciating her subhuman condition and that she has Lebensunwertes Leben (a life unworthy of life.) Therefore kindly, wise Dr. X will kill her despite her protests.

Report comment

“What’s to prevent shrinks from involuntarily euthanizing the “SMI”?”.

The fact that the law would require that it appears to be voluntary? Good news for doctors is that there are “added protections” in the new Mental Health Act our Minister tells us. What she didn’t say was that those protections only protect doctors from being sued for such treatments as ECT on teenagers. Sounds good in theory, I mean who in the community doesn’t want “added protections”?

There are doctors assisting “patients” to die all over the State every day.

https://thewest.com.au/news/health/perth-pro-euthanasia-dr-alida-lancee-cleared-of-wrongdoing-by-medical-board-ng-b88908204z

As the above case shows the authorities will not only look the other way but will actively subvert investigations to ensure the law is perverted. In my own instance where the necessary arrangemnets were made to murder me in an Emergency Dept police will actively assist doctors by doing deliveries of the people they want to euthanaze. Doctor rings police and says go get this “mental patient” for me and they will do deliveries like its a pizza bar service. Arrange an accident with some morphine and once again the matter is diverted from police and the death is listed as caused by morphine from an unknown source.

The thing is with regards the above case of Lancee she made all this noise, walked in to a police station and admitted killing a “patient”, provided them with the murder weapon and showed them where the body is and still they can’t do anything. “Not in the public interest” is what I was told by a lawyer. The Head of the AMA stated on the front of the newspaper that it was a matter that required a “sophisticated knowledge of the law” and Dr Lancee could call him to have the matter explained if she needed to be instructed in how to extinguish a “patient”. Can’t be too sophisticated a knowledge if a mug like me can figure out how organised crims have been knocking folk in our Emergency Depts. Coz believe me theres nothing sophisticated about me lol. Still, with me being slandered these folk have gone on for some time now without being noticed, and even when they did notice it’s “not in the public interest” to know that our hospitals are being infiltrated by crims and being used as their own personal slaughterhouse.

Maybe the Euthansasia laws will give some sort of method to restrict these convenience killings that are being done? At least limit them to “patients”who are seen to be dying within 6 months? Though with the levels of fraud in our system that protection will be easily overcome.

And then there’s our Chief Psychiatrist whose “expert legal advice” doesn’t extend to a knowledge of what a burden of proof is. That’s a major problem for the public that no one seems to want to recognise. Anyone want to look at his letter of response regarding my torture and kidnapping? More not in the public interest to know he wouldn’t pass a first year law or psychology course? Maybe he was just pulling my leg with a bit of gaslighting after becoming aware I had been subjected to 7 hours of torture and kidnapped by one of his Authorised Mental Health Practitioners? Who he claims can time travel and read minds by the way. Not that it would be considered refoulment of a victim of human rights abuses though, because they get to report on themselves, or so I’m told. All as a result of there being no effective mechanism for complaints regarding the use of known torture methods, despite this being a further breach of the Convention. Perhaps dealing with “patients” who have no human rights has lead to a false belief that no one has any human rights? Especially when citizens can be tortured and then made ointo mental patients post hoc to conceal the human rights abuses.

I have a set of fraudulent documents authorised by a Clinical Director of a major hospital that were sent to my lawyers that made a citizen who was tortured and kidnapped into a “mental patient” who had been at their hospital for more than 10 years. That’s real power when you can make anything you want to be true into a reality that no one will question. Because the public are so afraid of their own government they will allow them to do these cover ups and pray that it’s not them who is next.

Oh how I wish it were the case that the lunatics had taken over the asylum, but i’m afraid it’s much worse than you ever imagined. Noah said “expect rain” and they called him a madman.

Billy Connelly once said that Parliamnet is a place were good ideas go in and stupidity emerges at the other side. Pit Bull Terriers killing children, lets castrate them, no lets kill them, no lets castrate them then kill them, and what came out of the debate? The tattooed F%^kwits who own these dogs will have to get a permit from the post office costing 5 pounds. That’ll have them shaking in their boots

lol. Dont expect anything good to emerge from any debate about Euthanasia. Our legislation has been rushed through in record time and ensuring that the public don’t get to vote on it. Rushed legislation is bad legislation.

Report comment

There are unfortunately two issues being conflated here. One is whether an individual should have the right to access the knowledge and means to self-administer their own Final Exit and have supportive family and friends with them (which would currently be a crime.)

The other issue is whether doctors should have the right to administer life-ending treatments. They already do this: my fathers death was proof enough of this for me. Administering enough morphine to end his pain was also enough to stop his heart a few hours later. He could no longer tolerate dialysis and the other option would have been to allow toxins to build up in his blood until sepsis took him over a course of days to a week. So let’s be clear that families and doctors already make the decision to hasten death for incapacitated patients in pain.

The stigma against “mentally ill” patients ending their own pain has gone on for long enough. It’s origin is religious and the effect is cruel.

For anyone who thinks people already have the knowledge necessary to end their suffering, exhibit A is the number of unsuccessful attempts. The handbook on taking one’s own life – The Final Exit – is not for sale to under 50s, last I checked.

Jim Gottstien isn’t wrong about mission creep and a slippery slope, but let’s not pretend that “euthanasia” or hurrying death compassionately doesn’t already happen.

Report comment

True Kindredspirit.

Issue 1, I have seen absolutely no one ever charged with any offence related to being present when someone has committed suicide. Not saying it hasn’t happened but it might be like the law relating to the abuse of patients, half the penalties of abuse of animals and no cases ever been through the courts. People who abuse animals however may suffer consequences and have regularly appeared in the news being taken to court.

Issue 2.As the above link shows doctors do assist patients to die, and it is highly unlikely that they will ever be charged with any offence. In fact I think the last doctor to be charged with any related offence was Harold Shipman, and he killed quite a few before any questions were even asked. I heard that it was a joke among the villagers what he was doing and the only people who didn’t know were the authorities.

If the issue is unsuccessful attempts the those that fail seem to me to be being subjected to involuntary psychiatric ‘care’ which is basically a death sentence anyway. I’ve sat with patients and heard the discussions of what does and does not work. Would changing the law to allow access to this information change anything? We would never know given the current state of our laws because they have made sure that no data is to be collected.

Why would they want to keep such data hidden? I’m afraid one would have to ask our politicians and of course getting a straight answer from them is virtually impossible in these times of corruption. Its an issue of National Security i’m sure.

I made comment in another article about Zimbardo and his Lucifer Effect. Its quite easy to see how these types of laws introduced for all the ‘right’ reasons can later be tweaked and used for purposes they are unfit for in much the same way as the National Socialists did in Germany. I’m sure we would recognise if we were heading off down that path though, like his ‘prison guards’ recognised that they were transforming into brutal bastards in a very short period of time? Who remembers the reason for the introduction of Mental Health Acts? Such good intentions and here we are 2020 and MiA has come into being as a result of the disasterous consequences of those Acts. “Your human rights will be protected” and then they use that very legislation to abuse the human and civil rights of citizens and claim unintended consequenes. Coincidence that we made huge profits from our shares in the drug companies, and if you keep complaining we’ll call you mentally ill and have you treated.

Report comment

I agree Kindredspirit, I witnessed something similar play out in my mothers death. Rather than investigate what appeared to be an intestinal blockage (in an otherwise very healthy elderly woman) the doctors (along with a deviously inclined family member) decided – unbeknownst to me – it was “time for her to go”. She was a strong, resilient woman and had told me she didn’t want to die. But they stopped all nourishment and soon began to heavily sedate her. After 2 1/2 weeks it was obvious she was fighting to stay alive so one morning they pulled her hydration line apparently to speed things up. I had arrived to sit at her bedside again that night and could not get a straight answer why she no longer had a hydration line. As I sat next to her bed she began to make horrible gasping sounds at 10 pm. I called for a nurse and when she came she told me to tell my mom “it was okay to go”. Knowing how feisty she was and that she wanted to live made it very traumatic to watch her die a very painful death being so dehydrated her tongue hung out like a dog that died in the desert.

MAID (medical assistance in dying) has a double standard. It seems to be more about what is best for the professionals (or devious family members) rather than for the patient.

Report comment

I just downloaded “The Final Exit” to my kindle. It did not ask how old I was. (My kindle account is in the USA, not Oz, which I’m betting it’s not on the Oz list at all – the Oz list is highly censored in the name of “digital rights”)

Report comment

Jan, I‘m so sorry, I misremembered the title. The Peaceful Pill is what I meant to reference. It’s a guide on true death with dignity using specifically non-violent, peaceful means, but isn’t for sale to under 50s and I just confirmed that photo ID is required for purchase.

Report comment

Sorry to tell you but euthanizing happens daily, by psychiatry and medicine.

It is exactly what psychiatry does at the moment, through mental manipulation, and through drugs.

Suppose your parent tells you or treats you as if you are the doomed child, then you visit a shrink who not only tells you the same, treats you the same, BUT, he stamps it with his golden DSM and then hands you poison.

That my friend is slow euthanasia and often the patients just take the final step.

Psychiatry tells the public that it was the patient’s “original illness” that led to the act.

After psychiatry there is no “original”.

Treatment resistance is simply a worsening through being seen and treated as an illness, not a human.

Psychiatry has absolutely no vested interest in you as a human being. Psychiatry loathes others, especially the ones who do not need help.

They cannot stand weakness, because they were never allowed to indulge in it.

They cannot stand strength because it intimidates them.

Report comment

Too right, Sam.

These drugs are killing.

What matter, if the death takes 20 years instead of an instant? (it’s actually more painful this way)

Report comment

Anomie, the issue here not euthanasia per se but the legitimization of the concept of “mental illness” as a justification for this or anything.

Report comment

Reporting scientific studies is problematic when these studies are skewed and sometimes falsified.

Report comment

Thank you for sharing Dr. Dolinsky’s deeply tragic story, and honoring this beautiful man who suffered a most horrific iatrogenic injury.

Medication induced akathisia destroyed my life, my credibility, and stole my soul. It took me away from the only things that matter to me- being a loving and capable mother, wife and friend.

Psychiatry and pHarma are a joke, driven by greed, arrogance and ignorance.

May you RIP, Dr. Dolinsky.

Report comment

Good post Mr. Whitaker. Thanks.

One sobering thing to consider is that as awful as this story is, there are probably millions of other stories just like it in process right now. I personally know several friends, acquaintances, and others who have taken their own lives as a direct result of psychiatric abuse, whether they recognized the abuse or not.

The suffering Zel describes is real, and more awful than anyone who has not endured it can imagine. I honestly don’t know how I, or anyone else survives it, except for the help of God. I do not blame anyone who decides to enter the next phase of existence early, because I know just how terrible the suffering is. It is impossible to describe in words, and it will only be matched by the suffering that those who are responsible for it will have to undergo as a result of their crimes. For this reason, I pray for the perpetrators (i.e. proponents of psychiatry and so-called “mental health”) as well as the victims.

One thing is certain: mercy cannot rob justice. There will be an awful reckoning. The dragon of psychiatry will be slain, and all those who have perished by his fangs, claws, or fiery breath will be vindicated.

Report comment

Well said.

Report comment

Thanks. Danke schoen.

Report comment

Do you suffer akathasia Dragon Slayer? 🙁

Report comment

I suffered everything imaginable, and I was, for all intents and purposes, dead. The journey out of the psychiatric abyss was an unimaginable hell, and there were literally times when I thirsted first death because the pain was so intense. But I held on, or I should say, God preserved me for a purpose.

Report comment

I have found a path to healing, and akathisia is no longer an issue. Glory be to God, and not for my own strength, I emerged from the furnace of affliction stronger, more refined, and with an absolute conviction of the evil that is inherent in psychiatry.

Report comment

Glad your suffering ended before your life did.

The worst thing about psychiatric “remedies” is they cause exquisite suffering no onlooker can see. Even kind hearted people can’t appreciate the Hell that’s between your ears.

My mother would tearfully ask my shrink why I paced, jerked uncontrollably, had mini seizures, couldn’t carry on a conversation, concentrate or smile. “She never was like this.”

“Doc” M covered his butt with judicious victim blaming and gas lighting. Of course.

Report comment

That’s an excellent point Rachel777. Even the best of the critics of psychiatry, people like Breggin, Whitaker, Burstow, etc. don’t quite understand what a survivor understands. The work of these critics of psychiatry is indispensable, but only those who have survived psychiatry from the inside truly understand what is going on. That is why it is so important for survivors like you to stay strong and to articulate the truth about psychiatry.

Report comment

Similar thoughts had one can heard and much earlier. Can not be relied, what justice will triumph by herself. Of justice must achieve. Together.

Report comment

Hope you do not mind me posting this:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2017/10/childhood-victimization-connected-experiences-psychosis/#comment-115845

“Dear MIK

Thank you. I wish I could find anything that calms me but after being hospitalized 6 times via police and ambulance I can’t sleep anymore. I have been taken fro tm my condo because I wasn’t caring for it or myself after being returned there after being hospitalized. I had been a successful PhD researcher who at 50 lost his 13 year job through no fault of his own and an intimate relationship left me with no warning who because of a very complicated situation I had to see several times a week though I didn’t want to have anything to do with her. and after trying to hold it together for 5 yrs broke down in my Psychiatrists office because I was frustrated that meds were not working. I was not violent just very scared. Next thing he leaves the room and says it’s done and an ambulance and police take me to the hospital. In hospital I was taunted by staff and patients. One patient followed me around for 2 weeks telling me about judgement day and saying he would stick pencils in my ear. Another patient said he was the devil and referenced trying to help me in the past but now he was going to kill me and throw me in a dumpster. These were not hallucinations though I was heavily drugged. I’ve been placed in a “retirement” home single room and outside my window is a dumpster which is emptied many times a day night with loud noises that remind me of what the person in hospital told me. I am afraid to leave my room. I can’t think clearly anymore. I panic whenever I see an ambulance or hear a police siren which is often since older residents are being taken to the hospital daily. I feel like I am living in hell or feel I must be being punished. What scares me most is that I have been unable to sleep and am having violent thoughts when in the past I was a gentle introverted person.”

Report comment

Slaying the Dragon,

There are literally millions of stories like this in progress right now!

Report comment

True.

Report comment

Yes, like Slaying the Dragon and Fiachra say, millions of stories like this going on right now. It is abominable. I was almost a casuality in this same fashion, for the same reason. The abuse is profound, insidious, and thorough–mind, body, and spirit. Surviving meant moving entirely away from it, getting clarity, and seeing the big picture. Psychiatry has no moral compass, is clueless about humanity, and is destroying humankind, that is all too clear.

RIP Zel.

Report comment

Thank you Robert for sharing and honoring Zel’s tragic story with so much respect and compassion. Zel’s story is yet another tragic example of how degrading and dehumanizing psychiatry is for so many. As Zel said “I didn’t want to die but based on how I feel physically . . . I can’t live”. After my encounter with psychiatry I can totally relate to that, not wanting to die but needing the suffering and torment to end. In reality Zel didn’t end his life – psychiatry did.

Thank you for all the exhausting and astounding work you have done and continue to do on behalf of the millions who have been harmed and damaged and have no voice. May Zel find the comfort and peace he deserves in the next phase of life. RIP Zel.

Report comment

Hi Bob,

What stands out very strongly for me in Zel’s story is him asking you- “how do you think I felt?”… about being diagnosed and drugged- and him saying- “no one ever asked or ever seemed interested in how I really felt” about being sexually abused and traumatized as a child and labeled as schizophrenic- and- “ no one ever asked how I felt about being fed drugs.”

As a therapist whose primary commitment is always to provide a safe relationship where all such feelings can be expressed and received with compassion, I’ve served many people with very similar histories as Zels for 40 years. It is so tragic that in the last days of his life he still was asking for someone to listen to and receive his feelings, his emotional pain- emotional pain that kept being multiplied by the injurious human rights abuses of psychiatry, but by his own report, emotional pain that never was sufficiently received with compassion.

Report comment

Hi Bob,

“…That people diagnosed with schizophrenia needed to be on these drugs, and that to speak about research that questioned that belief, which I had done, was to expose people to harm…”

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_van_Os

“…In 2016 he published an editorial arguing that disease classifications should drop the concept of “schizophrenia”, as it is an unhelpful description of symptoms.[8]..”

I’d completely drop the term “schizophrenia” and not replace it with anything else – and concentrate on helping a person with (any) “problems” the person might have.

I’d see an approach like this eradicating “Schizophrenia” – but would this be whats wanted???

Report comment

Thank you, Bob, for this deeply moving piece. I say this as someone who worked as a neuroscientist for nearly 25 years, before closing down my laboratory in 2000, as I did not think that drug treatments for so-called psychiatric conditions were of value. I still work in the field of mental health – I prefer the expression ‘social and emotional wellbeing’ – addiction and trauma, just in a very different way to before. I am so glad I made that career change. RIP, Zel. You are a remarkable man and your words will add to the tide of change.

Report comment

This is just getting too creepy. I didn’t have an extensive or ongoing dialogue with Zel, but he was on my email list. The last I heard from him was when he thanked me for notifying him & others about Stephen Boren/Gilbert’s passing.

People have mentioned things like this coming in three’s, and wondered whether after losing Stephen and Julie another shoe was yet to drop. Hopefully there won’t be any more for a while, and people who feel they are at this point of despair will consider the option of actively exposing and confronting the system responsible for their lethal misery.

Farewell, Zel.

Report comment

Shit — Searching through my myriad emails I see that Zel did once briefly describe his situation to me, and mentioned looking forward to my comments “as long as I’m around.” To which I responded “Hope you’re not planning to go too far.” He then described his drug situation and said that he hadn’t slept in 7 years (I remember asking someone else if that was physically possible). But I never had any further dialogue with him so am of course now contemplating what possible things I “should have” done or said. Not that it would have had much effect on neurotoxic brain damage.

Quoting Phil Ochs, too many martyrs and too many deaths.

Report comment

And Matt Stevensons (death), not too long after exposing and campaigning under his own identity.

Report comment

I think of Matt often. I didn’t know him personally so I’m not sure why I was so effected by his death other than I identified so strongly with his particular struggles that he spoke of here.

Report comment

Matt’s death had nothing to do with his outing his own name. This is a false issue that Matt struggled with and needs to be rejected — the idea that there is something disingenuous or cowardly about using a pseudonym. I hope no one else is feeling such pressure, and urge those who would make such implications to cease and desist. What’s in a name anyway?

Report comment

Thank you for this wonderful tribute to Del; he bore witness to the cruelty of addressing childhood trauma with critical labels and drugs for the victims.

Report comment

To do it correctly, you’d need to replace “schizophrenia” with a number of terms. “Schizophrenia” isn’t a disease at all, but a syndrome- a collection of symptoms and signs with multiple possible origins and treatments- no “one treatment fits all.”

Report comment

No, you don’t need to replace it. You need to abandon it.

Report comment

“Schizophrenia” isn’t a disease, it’s an insult. You don’t know how many times I’ve talked to people about “mental illness”, so-called, and have gotten this thing about the hopelessly deteriorated and deteriorating “schizophrenic”. Most people seem to “know” one. This person or that deemed beyond “recovery”. Far be it for me to explain that I once had a “schizophrenic” diagnosis lodged against me. I don’t think confessing would help me one iota. Also, I’d have to admit, I don’t have anything to confess. I would never be one to apply such an insult to myself.

Report comment

I don’t know, maybe it would be fun to interrupt someone’s tirade and say, “You know I was considered one of ‘those people’ once. Do I seem crazy, dangerous or hopeless to you?” Might toss a monkey wrench in their works.

BUt I also get why you wouldn’t want to go there. People who are on that kind of trip really NEED to believe what they are saying, and even a big dose of “cognitive dissonance” rarely has any effect.

Report comment

There’s a Licence To Kill on “Schizophrenics” so it’s not good to be one of them.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/114Qjp47-TmI0LJWlyKRmrC7R4QLtHITq/view?usp=drivesdk

(And the country I come from biggest Export is Pharmaceuticals).

Report comment

This particular research study team….

DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTIC REVISITED

https://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/ps.49.10.1361-b

…includes a C.P.N. nurse who actually called at my house in Ireland in the 1980s when I refused to take my monthly depot injection. When I explained the problems I was having with Akathisia to him, he was at the time sympathetic – but he did NOT record my problems on the records.

The above study does refer to extrapyrammidal movement problems BUT does NOT refer to Akathisia Induced Suicide – which is something the Authors were Aware of.

The Psychologist at the same Psychiatric Unit as I attended, promised me in the 1980s that ALL the “patients” attending could make complete recovery without medication and through psychology.

Report comment

Another heartbreaking story of a life curtailed by psychiatry. I understand Zel’s desire for a dignified death and agree that it is a human right.

Report comment

RW — Any luck finding the person Zel wanted to care for his cat? I’m know that had to be very important to him. I worry still about the well-being of Julie’s dog Puzzle. (Sweeney, Stephen’s cat, is in good hands I hear.)

Report comment

Psychiatrists determine a person’s will as disease. That is, the man himself is a disease. And they rid a person of such an illness. That is from himself. It is not surprising that having the prospect of such a “treatment”, the biggest loving life human will prefer to die.

Report comment

Thank you, Bob, for sharing Zel’s story. It is heartbreaking to know of his work and his dedication to science and his own suffering due to the drugs that so many of us have been told are the answer to our emotional distress. It is hard to imagine akathisia so bad that one cannot sleep, and that sounds like an awful way to try to live. MIA is doing great work here, and I wish doctors from all over the world would read Zel’s story and face the truth.

Reading MIA and reading mainstream media info on psych drugs and their efficacy is like living in two different worlds—right next to each other, but so far away. Stories are a powerful way to get at the truth, and Zel’s is powerful, brave, and profoundly sad.

Report comment

Before commenting I’ve read this post over several times along with the comments.

Although this is just a glimpse into his life and diverse perspectives, Mr. Dolinsky left behind a very powerful testimony, especially on how the use of psychiatric drugs can lead to unbearable internal suffering, the belief of hopelessness and a death wish. Obviously he was a very intelligent and resilient individual who accomplished a lot during his lifetime. It is unfortunate that despite all of his knowledge, access to resources and personal testimonies of recovery, he lost all faith and was unable to find the answers and relief he needed, especially considering he made a drastic career change later in life to provide holistic healthcare to others as a licensed massage therapist in a hospital setting.

Psychiatric euthanasia is a topic considered in Kevin Dunn’s film Fatal Flaws. The documentary features a young Dutch girl who was euthanized last January because of her “severe psychiatric problems” that psychiatric treatment failed to relieve. Psychiatric euthanasia has steadily increased in the Neatherlands with 83 reported cases in 2017.

Adam Maier-Clayton, a Canadian psychiatric Death with Dignity activist, committed suicide two years ago because of suffering from what he and his family believed were symptoms of “severe mental illness” that became treatment resistent. Many of his complaints sounded like adverse reactions to psychiatric drugs.

Euthanizing psychiatric patients is a topic that deserves thoughtful consideration and expanded awareness, especially among pro-psychiatry drug advocates like Pete Earley and DJ Jaffee.

As Severe Mental Illness advocates, Mr. Earley and Mr. Jaffee work to advance the use of psychiatric drugs and forced drugging. Both men clearly disregard and downplay adverse reactions to psychiatric drugs.

Supporting Death with Dignity for psychiatric patients seems like it would place professionals in a difficult situation of trying to distinguish between a patient who qualifies for forced treatment because they are suicidal and a patient who qualifies for euthanasia because they have a legitamate reason to be suicidal. For patients who are considered “treatment resistant”, it also seems impossible to define the suffering as being caused by the perceived “mental illness”, or being from an actual adverse reactions to psychiatric drug therapy or withdrawal syndrome.

Psychiatric drugs are often prescribed by doctors who fail to test for and treat possible underlying medical conditions that can manifest as a “mental illness”. Without treating the underlying cause, there is little hope a patient will ever find relief, thereby increasing the chance psychiatric patients would welcome relief through euthanasia. Sadly, family members of “mentally ill” patients who find it difficult or even impossible to help their loved ones and can easily feel overburdened by their care, also seem to give up hope and welcome relief through assisted suicide for their loved one.

Historically, individuals with perceived “mental illnesses” have been victims of eugenic movements and treated like the throw-aways in our society.